| John Costello |

Casablanca plays on glorious 35mm at the Trylon Cinema from Sunday, August 17th, through Tuesday, August 19th. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

Two-thirds of the way through Casablanca (1942), the action pauses in Rick’s Café Américain to dwell on three minor characters seated at one of the tables. Instead of another scene involving a pickpocket or a musical number advancing the story, the camera lingers on an elderly couple, the Leuchtags. Carl, a waiter, accepts their invitation to sit and share a drink in celebration. The couple have finally gotten their paperwork to travel to America.

The Leuchtags don’t explain how they secured their papers, and Carl doesn’t ask. What matters is the future. By this point in the movie, the viewer understands that exit visas are acquired either by paying large sums of cash or trading sexual favors with Louis Renault, the head of the French police in Casablanca. The Leuchtags appear wealthy enough to have paid the necessary bribes. Carl and the Leuchtags toast America, the goal for the refugees who have fled the Nazi advance across Europe and now are stuck in Casablanca.

Initially, Carl speaks only German to the Leuchtags. Mr. Leuchtag informs Carl that they are speaking nothing but English. They want to feel at home in America. Then Mr. Leuchtag slips, addressing his wife as “Liebchen” before reverting to English. “What watch?” he asks her. “Ten watch,” she answers. “Such watch,” Mr. Leuchtag says. They have confused the English words for “time” and “o’clock” for “watch,” revealing their limited command of English.

Somber-faced, Carl tells them, “You will get along beautifully in America.” The Leuchtags have no choice. At least they have each other.

Set against the bravado, the action, the conniving, and the knowing comments from various characters, the scene with the Leuchtags seems misplaced and sentimental, a distraction. The beat provides a rest after yet another scene with a menacing Nazi while setting up a scene between Rick and a newlywed woman, Annina, who with her husband cannot afford to pay the bribes required to obtain a visa. Louis has directed Annina to speak with Rick as a kind of character reference to verify whether the policeman can be trusted to uphold his side of the bargain, sex in exchange for passage from Casablanca. Louis suspects that Rick possesses stolen exit visas, testing whether he will help this young woman.

The setup for the film is straightforward: Everybody comes to Rick’s. (This was the title of the play that was adapted into the film.) The man who killed German couriers carrying irrevocable exit visas enabling passage from Casablanca to Lisbon, and from there America. Victor Laszlo, a leader of the Resistance, and his wife, Ilsa Lund, who is also deeply involved in the resistance to Nazidom. People attracted to the illegal gambling room. Diners and drinkers enjoying the musical acts. A Nazi major trying to neutralize the Resistance leader. Louis Renault searching for the stolen exit visas. Ilsa Lund, the woman who jilted Rick in Paris and is still loved by him.

In Casablanca, the relevant heroic mode is sacrifice. The city is controlled by Vichy France, the collaboration government installed by the Nazis after they defeated the French Army and seized Paris. The common approach to survival, promoted by Louis, is to take for oneself. Sacrifice is a burden assumed by others.

Rick claims to be neutral, but Louis accuses him of being guided more by sentimentality toward others than by self-interest.

When Ilsa first appears, at the same time as Victor, only Victor’s name has been mentioned. Initially, Ilsa is referred to only as his wife, not named. You’ll be forgiven for not noticing the way she looks around the dining room and stares at Sam, the piano player, who startles in recognition. So focused is the camera on Victor during the entrance, it’s easy to ignore what Ilsa is doing.

Ilsa’s connection with Rick and Victor gives the film a wonderful sense of uncertainty, much of it driven by Rick, who is anything but neutral when it comes to Ilsa. He is bitingly sarcastic to her face, and the tough guy façade crumbles into resentment and self-pitying behavior after she leaves. He stays behind drinking after the café has closed, knowing Ilsa will visit him, then mocks her again to her face. He’s bitter, jilted, and untrusting.

When Annina speaks with Rick, she describes her moral struggle with the policeman’s proposition. Rick suggests she return to her native Bulgaria, which at this point in the war had allied itself with the Nazis.

“The Devil has the people by the throat,” Annina says. Better to escape Europe. She reasons that having sex with Louis is forgivable if she hides the deed from her husband. It’s clear she’s trying to convince herself and is seeking Rick’s guidance and approval. She asks him to agree that such an act isn’t a betrayal, so long as her husband never learns of it.

When Annina asks Rick if he could forgive someone who loved him and did a bad thing to ensure his happiness, he withdraws into self-reflection. To this point in the movie, Rick has relied on humor to deflect serious conversations. He is consumed by the belief that Ilsa never loved him.

You may wonder why people respect this Rick and seek his advice. He fought against the Fascists in Spain and ran guns to Ethiopia, helping that country resist the Italian Fascist invasion. They respect him for what he did before World War II, even though he now maintains neutrality. He employs the best piano player in Casablanca, Sam, who followed him from Paris. Even Louis seems to respect him.

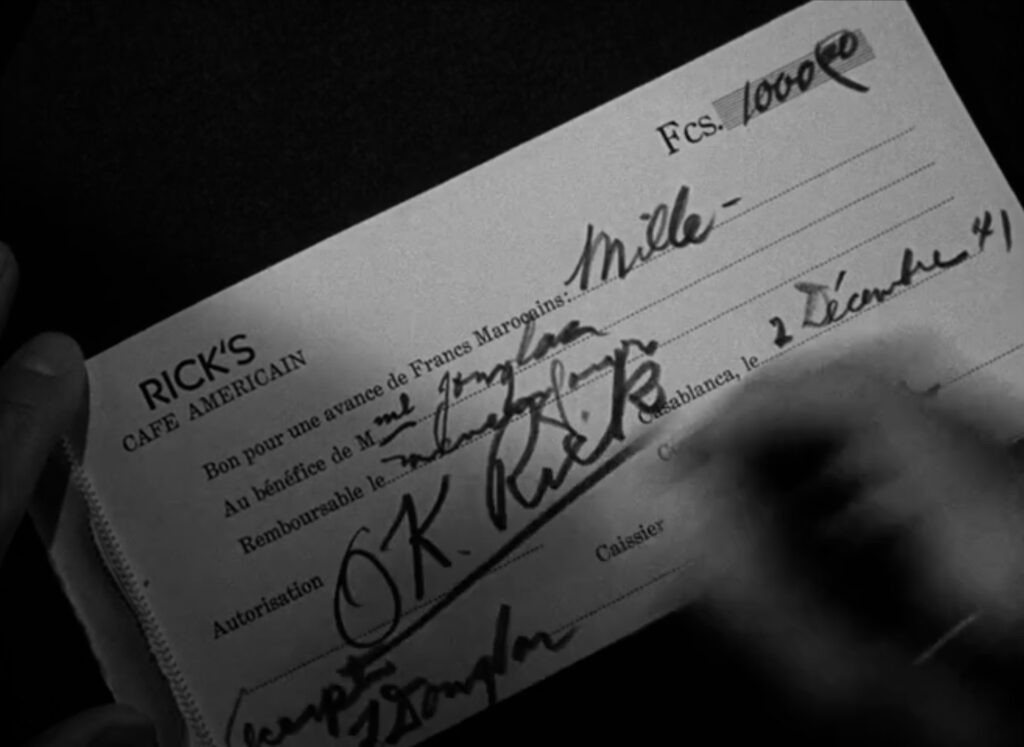

Rick avoids heroism to safeguard his business and his life. Besides, it’s December 2, 1941. America isn’t yet involved in the war. Yet, the Nazis suspect him.

For much of the movie, Ilsa and Louis act, while Rick snipes at people and fails to make much of a difference. Rick tries to preserve the status quo in a world overrun by war.

If the scene with the Leuchtags demonstrates the challenges refugees will face in America, Annina’s scene with Rick shows how vulnerable these would-be immigrants are to exploitation. Rick realizes Louis has presented Rick with a choice to help Annina or be complicit in her exploitation, a test of Rick’s sentimentality. Rick chooses to help. The action costs his casino money, a small sacrifice. What matters is that he’s no longer neutral to the suffering around him.

The crack in Rick’s neutrality widens when a group of Nazis commandeer Sam’s piano. The Nazis sing “Die Wacht am Rhein” (“Watch on the Rhine”), a lied with anti-French origins dating to Franco-Prussian conflicts in the Nineteenth Century. Singing the song in territory claimed by Vichy France, the song becomes a demonstration of power.

In response, Victor tells the café band to play “La Marseillaise,” the French national anthem. (Never mind, for a moment, that “La Marseillaise” calls for purging “impure blood” while here being sung to show opposition to a eugenicist, genocidal regime.) Rick nods his approval, a pivotal moment. Although he has chosen sides, he hasn’t revealed this to the Nazis. Even so, the action has consequences.

Yvonne, played by the French-born Madeleine Lebeau, sings boisterously, tears streaming down her face as she belts the lyrics calling citizens to pick up arms and march against tyranny. Early in the film, Yvonne was jilted by Rick, later causing a brawl in his café when she brought a Nazi soldier as a date to the bar. Now, when “La Marseillaise” ends, Yvonne alone shouts, “Vive La France! Vive la liberté!” Long live France. Long live freedom. It is a dangerous gesture, an open and necessary act of resistance.

The Nazis order the café closed. Victor is almost captured at a Resistance meeting with Carl. The minor characters, including Carl and Yvonne, disappear from the story, their histories soon to be swept up by America’s entry into the war, Rommel’s invasion of North Africa, and the surrender of Vichy.

Ilsa, recognizing the danger to Victor, confronts Rick about the stolen exit visas. He’s possessed them almost since the film’s beginning. Tormented by her love of two men, Ilsa collapses into indecision. It’s tempting to retroactively apply modern notions of heroines and unsatisfying to defend her portrayal as a symptom of prevailing social attitudes during the war. She must choose between Victor, the Resistance leader she married, and Rick, with whom she found happiness and escape after she thought Victor had died. She yields the decision to Rick, which in ways is worse for him. She doesn’t love him enough to sacrifice another outright.

A scramble to sacrifice in the name of love ensues. Louis circles like a desperate dog, seeking to capture Victor and please his Nazi masters. Rick and Victor declare the importance of rescuing Ilsa, scheming about who else to save and how.

In the end, Rick sacrifices his own safety, entering the fight against fascism again, and in doing so, rebuffs Victor’s own attempt to sacrifice himself for Ilsa. The greater sacrifice comes from both Ilsa and Rick, the pair lying in the final scene by declaring that they no longer love each other. Every scene of Rick’s sulking and Ilsa’s tears at leaving him behind tell a different story.

When Louis observes this lie to Rick, Rick responds, “Anyway, thanks for helping me out.” His mask of detachment is firmly back in place.

“You are not only a sentimentalist, you are a patriot,” Louis declares, before joining Rick to trek from Casablanca to a Free French garrison, a small sacrifice for the French policeman who leaves behind a dead Nazi officer for the possibility of freedom, if not in America, then in his native France.

Rick and Ilsa have about their love for the sake of Victor and furthering the Resistance, a heroic, ugly sacrifice of love for the sake of war. They are leaving the relative safety of Casablanca, one with her husband to the freedom of America and the other to the desert. For Rick and Ilsa, there is no happiness like that of the Leuchtags or Annina and Jan. Their happiness remains behind them. Their hope lies ahead.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon