|Kit Stookey|

Night of the Living Dead plays at the Trylon Cinema Wednesday, September 24th. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

It is common wisdom that any given piece of media says more about the period in which it was produced than the period it was trying to portray. The Night of the Living Dead is no exception. Viewing it through the lens of the Vietnam War, it is easy to compare the “shoot first, ask questions later” approach of the police and local militia to that of the American approach to global geopolitics that allows for deaths of innocents without so much as a glance back over the shoulder. Having Ben played by Duane Jones without changing any of the dialogue to reflect his Blackness, while the original character was imagined as white,1 emphasizes both the heroism and the disproportionate loss of Black American soldiers in the Vietnam War. However, as a native Pennsylvanian who has now lived in the Pittsburgh region for seven years, I would say its location is just as integral as understanding the impact of Night and perhaps allows it to translate more easily for a modern viewer.

While the film begins following a more conventional heroine for the time in Barbara, Ben proves to be the true hero of Night. Barbara is no doubt sympathetic as she urges her brother to do the right thing by visiting their father’s grave on behalf of their elderly mother. As she kneels by his grave and clasps her hands in prayer, she is the vision of virtue, an upstanding citizen. However, there is little use for virtue and manners in the world of ghouls. When one approaches her and her brother, she immediately panics, locking herself in a car to which she doesn’t have the keys. She runs and hides in the house and spirals into incoherency at the trauma of witnessing her brother’s death.

Ben, on the other hand, is cool and decisive when he comes into the house, immediately trying to find keys for the gas pump, gather food, and board up the house once it becomes apparent that they can’t leave anytime soon. He is the one who discovers that the ghouls hate light after watching them bust the car’s headlights and sets a corpse on fire to deter the ghouls. He even has the heart to try and find Barbara a pair of shoes—a touch of humanity amongst the horror. None of the other characters in Night even come close to Ben’s level of heroism, intelligence, and kindness. Harry is a little man who wants to be big but refuses to go out of his way to help anyone but himself, demanding that a nigh-catatonic Barbara pay attention to Ben so he doesn’t have her life in his hands and refusing to open up the door when Ben is chased by ghouls. Tom is smart enough to follow a leader who knows what he’s doing but doesn’t come up with ideas himself—he and his girlfriend, Judy, do nothing to the house until Harry, Helen, and Carrie arrive and board up the cellar. And even ignoring Barbara, this film doesn’t think highly of its female characters. Helen is too busy caring for her daughter to offer much assistance other than sniping at her husband, and Judy is prone to reckless decisions, like following her boyfriend to the truck when there was no reason to. Ben, in spite of some of his morally gray actions, like shooting Harry after he tried to turn a gun on him, is the only real hero of Night.

There is no doubt that Duane Jones brought much of his lived experience to the role of Ben, even as the script remained unchanged. A graduate of the University of Pittsburgh who completed a Master’s degree in New York in between shooting Night, Jones embodied “Black excellence” before it became a buzzword. In his short life, Jones led English departments at Harlem Preparatory School and Antioch College, designed English language training programs for the Peace Corps, and served as a mentor for many diverse actors seeking to break into the industry. Jones was the one who re-imagined Ben beyond an uneducated truck driver helplessly caught in a freaky ghoulish fray to a cool-headed leader, trying his best to save those too panicked and too petty to acknowledge his good ideas. It is through Jones’s vision that Ben became the tragic figure, mistaken for a ghoul but perhaps more human than anyone else on the screen, who holds the heart and soul of Night.

Still, there are many Bens in Pennsylvania—Black people seen as less than human, treated like ghouls and threats to the safety of heart and home. Evans City, where Night was shot, and Butler County, exemplify the culture of fear and othering surrounding blackness in Pennsylvania. Evans City is a town of just over 2,000 people, 30 miles outside of the Pittsburgh City limits, 97% white but situated in a county obsessed with the specter of Blackness. Local Butler County businessman, John Placek, is known for his controversial and tasteless billboards along Route 422. One billboard from two years ago decried that “whites are under attack—stop it now!!!” Placek has not relented and cannot even see his own racism. Last year, leading up to the 2024 presidential election, Placek’s billboard read “Black’s got it right… Don’t trust the legal system!!!” with a picture of Trump’s mugshot on the right and a Black man wearing an orange jumpsuit, behind bars, on the left. Placek can only imagine a Black American who is naïve enough to conflate the historical struggle of a people against a system founded on racism with one mediocre to insane to evil white guy rigging elections to try and make himself king. I doubt that Placek, a lifelong resident of the bordering, 98% white Armstrong County has had enough interactions with Black people to possibly correct his racist assumptions.

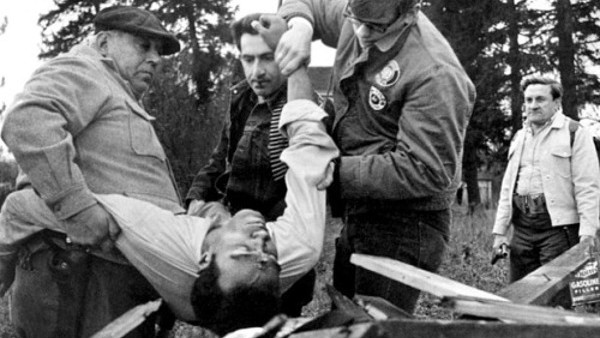

Of course, white people can interact with Black people every day and still be racist. George Romero’s hometown and my adoptive home of Pittsburgh, PA, is proof of this. The summer before I moved to Pittsburgh, 17-year-old Antwon Rose II was murdered in cold blood by a cop fresh to the Pittsburgh police force. Although the death of Antwon Rose II did not reach the national profile of that of George Floyd, it is still talked about and still seen as evidence of injustice more than seven years later. However, the systemic murder of Black Pittsburgh residents by the failures of our healthcare system is even more shocking. Pittsburgh, the home of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center—the largest non-governmental employer in the state of Pennsylvania—is also where Black people face the poorest health outcomes. According to a 2019 study by Pittsburgh’s Gender Equity Commission, Black women are more likely to die in pregnancy in Pittsburgh than they are in 97% of other cities in the United States. Black men in Pittsburgh have a higher risk of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and drug overdoses compared to peers in other cities. One sociologist affiliated with the University of Pittsburgh stated that Black people could live in nearly any other U.S. city and expect better health outcomes; one can only posit that in another city, another state, Ben may not have been mistaken for a ghoulish killer but the hero that he was.

I have spent most of this essay talking about Western Pennsylvania, and one could get the false impression that the eastern end of the state may be a comparative racial utopia. I want to assure you that is not true—that Ben could easily have died in my hometown as Evansville. I grew up in a small town that is technically only 45 minutes outside of Philadelphia but in a locale that felt more like Pennsyltucky, rife with cows, cornfields, and Confederate flag bumper stickers. My education emphasized that Pennsylvania, founded by the Quakers featured on your oatmeal, was the first “free state,” that we were somehow magically more enlightened than the states that relied on slave labor in their agricultural economies. I could count the number of Black classmates I had on one hand; it was only in adulthood that I learned that my family lived in our specific town to avoid the busing of Black students just across the border in Delaware and thereby have access to a “better education.” Like many white people, used to privilege, used to faces that look identical to mine, I have not often been encouraged to think about racism outside the context of mandatory diversity and inclusion seminars at work and school. Like many white people, I have deeply ingrained biases that I am trying to eradicate, but probably never will. Like many white people, I am fully capable of mistaking Ben for a zombie, capable of shooting him without a second thought. Like the militia in Night, I am a product of my context. I am a product of Pennsylvania.

Notes:

- Alan Jones The Rough Guide to Horror Movies, London: Rough Guides, 2005. ↩︎

Edited by Finn Odum