|Zach Staads|

Kuroneko plays in glorious 35mm at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, October 10 to Sunday, October 12. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

“We are all unwavering bands of light.” – Kurt Vonnegut

I’ve used this quote at the top with almost no context for where it comes from or what it means. I’m not even checking to see if the person who quoted this is correct, and that this is something Kurt Vonnegut said or wrote. I quote it to illustrate how people commonly seem to feel about light. We think of light in a metaphorical sense as some greater thing; light is warming, blinding, harsh, beautiful, deific, and other words that describe what I’m describing. When we use light, we often just flick on a switch and bathe a room in a functional or semi-atmospheric light. But we can have more fun than that.

Whether it’s the pink light pouring from the door in Moonlight, the expressionistic colors and frame shaping in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, or the various theatrical blackouts, spotlights, and dramatic flourishes of The Ballad of Narayama (1958), there are so many gosh-darn cool things that inventive filmmakers can do with light on screen! Kuroneko is one of the ones that, I’d argue, does it best.

There are three main ways that this is best expressed throughout the film:

Theatricality:

Who doesn’t love a little razzmatazz? It’s so fun to see different bells and whistles, not just a cut but a transition through moving scenic elements and lighting, spotlights coming on and revealing things or going out and hiding them, and the art of blocking out a perfect frame through perspective, design, and rehearsal. These elements, this mixing of mediums, can create a visual marvel without the use or need of intense CGI.

This aspect is certainly expressed through the lighting throughout the whole movie. Shadows proliferate on walls and faces, creating power dynamics and fear. Glowing edges and silhouettes are created with intense backlighting to bring us into a world inhabited by spirits, and costumes are made to look intensely black and white with little gray when seen on celluloid.

Japanese theatrical styles also make their way into this film and help to elevate not just the lighting, but every corner of the film. Kabuki influences seep into the film’s presentation and styling of the big, fluid movements of the spirits, some of the more absurd and surreal hair and costume choices, and—at times—the performances themselves (particularly Nakamura as Gintoki, the son). Aspects of Noh theatre can be seen in the particularly controlled walks and movements of Otowa and Taichi, our mother and wife pair.

Encroaching Darkness:

An image dominated by darkness has a certain raw power, both on film and on stage. It’s hard to achieve and there is constant back-and-forth between what light level is perfect, especially when it comes to lighting an evening or night scene. While there are extremes in many directions (dark to the point of muddy, spotty day-for-night looks, lack of commitment to a stylization, I think that when darkness is allowed to envelop a scene without losing clarity of what the scene’s intention is—that’s when a film hits gold.

There’s something so evocative in the different shot compositions throughout this film and how many of them are bathed in darkness to make only the most important pieces pop. Whenever a samurai on a horse rides up to Rajomon Gate, we get the vague outlines and silhouettes of structures and trees around him, of the hill he’s on, and a single rooftop bathed in moonlight. It creates an elegant and eerie visual frame that is lit up in a way that accentuates the use of negative space.1

There is power in negative space that speaks volumes, even in smaller moments, like when we are first being introduced to the house in which a majority of the film takes place. The bottom of the frame is occupied by the house itself, but the top is filled with the bamboo of the grove. The camera moves past the bamboo while the house remains stationary below. The house is brightly lit but the grove above is barely lit and ominous, instilling a sense of dread and enclosing the image in that encroaching darkness.

The Void and what lies within:

There is nothing quite like seeing what feels like real magic on screen. With clever lighting and blocking, it is as though the spirits of these people are truly manifesting out of thin air. It fills me with a sense of awe.

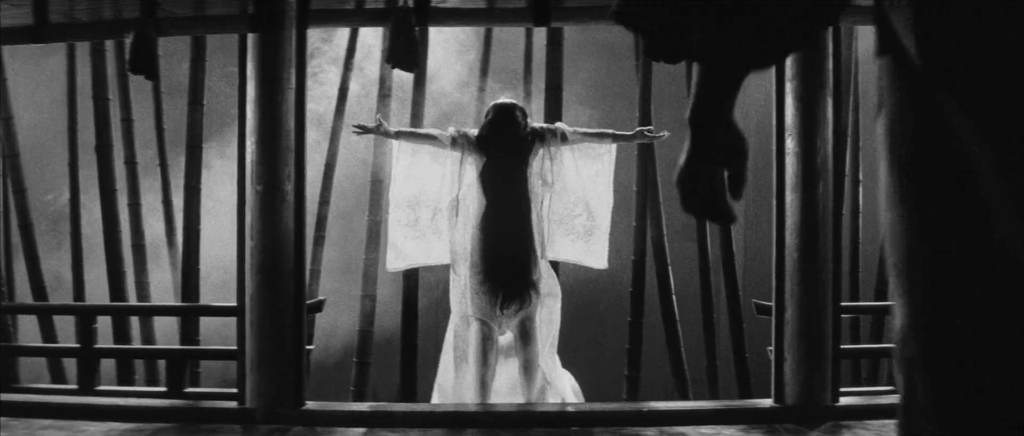

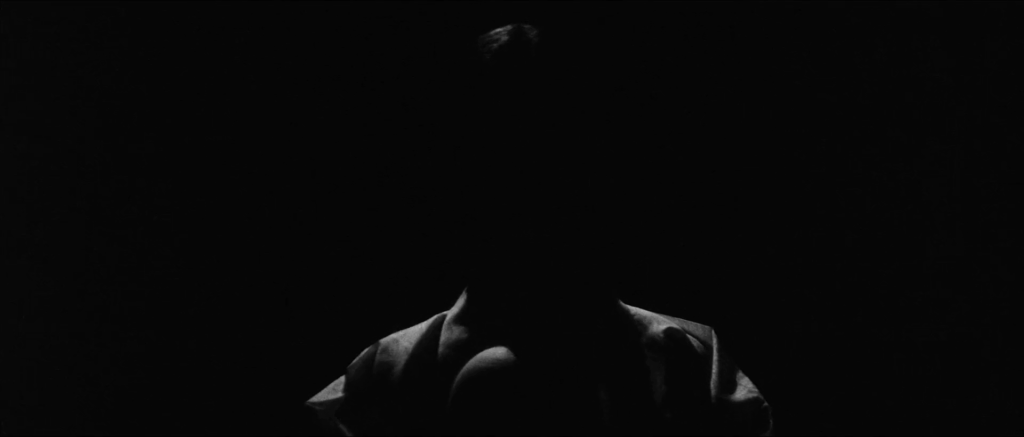

There’s an immaterial quality within the unique grayscale of black and white film; translucent fabrics and fog have a spirituality to them; an otherworldly eeriness is evoked as things appear, suddenly, from the gaping maw of the void; and people can disappear or hide as light is snuffed out. Countless scenes use this technique, when the spirits emerge from shadow itself to greet samurai at the gate, Shige spreading her arms joyfully, wearing a ghostly robe (seen in the header photo of the article), and when Yone does a silent front flip over a samurai on his horse, where the two of them are the only things visible in frame. The moment that stands out the most is the one pictured above, when the sequence of killings hits its keenest stride.

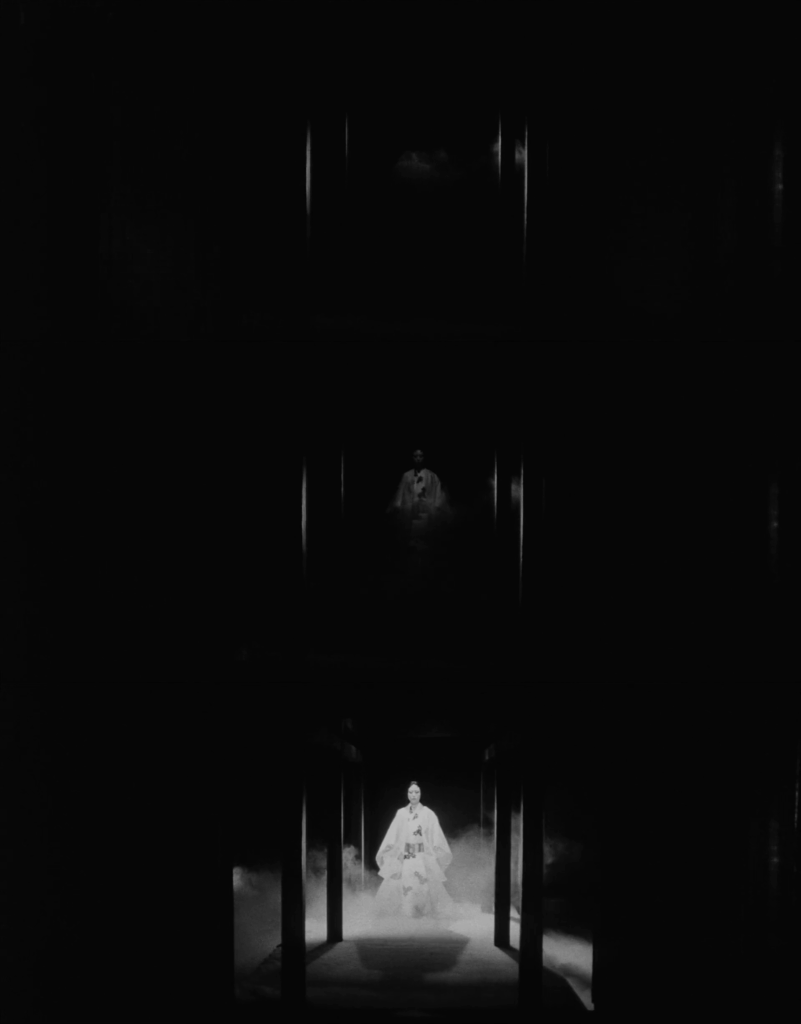

The specter of Shige distracts an intoxicated, lustful samurai, and he stumbles into the center of frame, covering the hallway behind him. Once he moves, there is the faintest spectral glow from within the hall which lingers for a hair’s breadth of a second, before the hallway is filled with light and fog as Yone’s spirit begins a ritualistic dancing.2

This is what can be achieved on a practical level on film. With enough effort, timing, and commitment, you can create moments that feel frightening and exhilarating with a simple trick of sense manipulation through light. I’ve always tried to make big choices in my own artistic work when it comes to light, and it’s films like this that really feed that impulse. They push me to find new, clever ways to present things in the context of how they’re lit on screen and the possibilities of what we can do, even with limited budget and technology.

Whether you are blasting an actor with a spotlight for dramatic effect, using intense colors on camera instead of in the color-grade, trusting in the power of darkness, or attempting a symphony of slowly raising several lights at once, at different speeds, while an actor needs to perform on screen in tandem with the lighting changes—these things bring me joy.

Lighting used to be something very dramatic and interesting in film, and now it has flattened. The well has dried up as filmmakers go to it less and less. I think it’s time that we embrace this style again, I know I am! The script of my next short film is inundated with over-the-top theatricality and lighting choices that will hopefully be moving.

Even if it doesn’t work out, if it ends up not working out how I want it to, at least I went for it and had some fun. I hope you have some fun too, even if it’s just going home and putting in a stained-glass bulb in your lamp.

- You can read more about the use of negative space, one of my favorite elements of art, in a previous article of mine, here. ↩︎

- An artistic aside, it is never explained what this dancing is but I view it as a stoic dance of vengeance that, once Gintoki arrives, becomes somber as the vengeance is not taken and Shige resigns herself to a terrible fate to enjoy a few more days with her husband. ↩︎

Edited by Finn Odum