|Jillian Nelson|

Rosemary’s Baby plays in glorious 35mm at the Trylon Cinema from Sunday, October 12 to Tuesday, October 14. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

When Rosemary’s Baby released in 1968, conflicts over women’s rights raged on as second-wave feminists battled governmental restrictions that seeped into interpersonal relations. Birth control pills had only just been made legal. New York had recently lost its attempt to legalize abortion and the procedure remained illegal in every state. The right for women to open a bank account without a male co-signer would remain legally unprotected until 1974, restricting women’s ability to own property and live independently. Marital rape didn’t even exist as a legal term until 1984. Under the government’s thumb, a woman’s being was reduced to pregnancy and marriage, and the culturally acceptable ideal of womanhood remained becoming a housewife. Sounds familiar, doesn’t it?

Although counterculture efforts were creating spaces for women’s independence, the cult of domesticity reigned. The Western association of female corporeality with domestic interior space laid the cornerstone for this ideology. Through patriarchal law and societal representation, the boundaries of a woman’s sexual embodiment were equated with the boundaries of the home. Contained, docile, safe. Where women’s true power and individuality could flourish. Eye roll. This is the framework of Rosemary’s world.

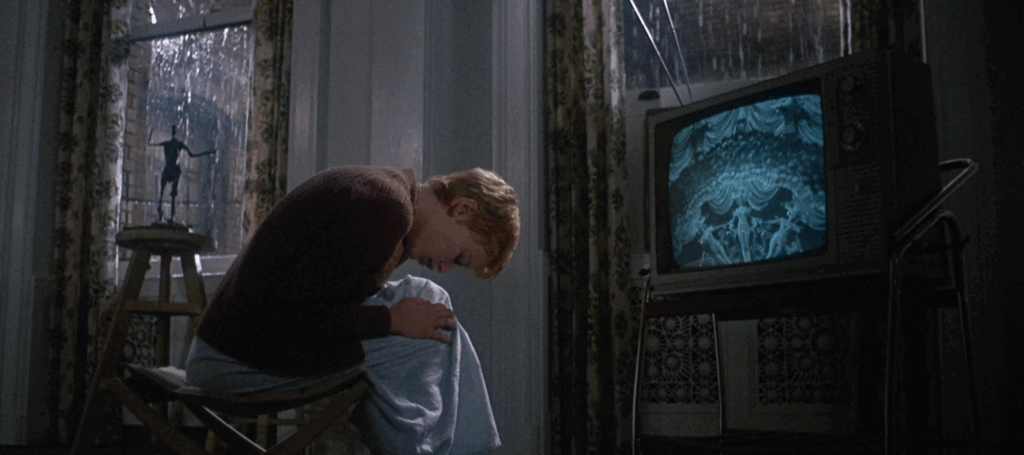

The film critiques precisely this cultural ideal, unraveling the autonomous 60s housewife. Wielding the apartment as the main setting, it dissects the patriarchal forces behind the analogy of woman to house. The film initially aligns Rosemary with the false promises of housewifery, presenting her as possessing a certain level of control. She encourages Guy to take the apartment she desires, initiates sex, exerts power over interior decorating and domestic life, and self-advocates for pregnancy. The apartment reflects her sense of agency as she decorates it an inviting yellow, its roominess warm and safe. This space, where she expresses her individuality, is hers. Over time, the aesthetics and spatial use of the apartment change, reflecting the slow stripping away of her health and personhood as her concerns over her pregnancy pain are undermined. In a particularly haunting scene, she hunches in front of her TV writhing in pain as rain pours down outside. The blue, dark lighting and low angle construct the space as a cold, unyielding force that looms so large it smothers her. Through the visually, spatially morphing apartment, the film illustrates the “ideal” 60s home as not a place of freedom, but rather a space designed to contain and isolate women.

The film presents the home as simultaneously a space where women are confined and where their subjectivity too unbinds. Rosemary frequently hears the Castavets’ voices through the paper-thin walls and Minnie frequently visits uninvited. The boundary between their apartments becomes fluid during the final act. In an attempt to locate her stolen baby, Rosemary intuitively pieces together that the storage closet has a false back, revealing the connection between their places. The apartment’s malleable borders collapse the dominant ideology that the home is inherent to a woman’s bodily autonomy. This challenges the dominant understanding of the self, a masculine ideal that presumes a fixed, bordered being, and illustrates its incompatibility with female subjectivity under the Nixon administration. Oppressive law bleeds into domestic life, obliterating the female body’s borders. Women like Rosemary become objectified and dehumanized, reduced to their use-value for reproduction. The female self’s boundaries are erased, revealing that there is no coherent female self to begin with. The film calls into question, who is this doubled space (the home/woman’s body) truly for?

The Castevets’ cult and Guy’s manipulation and abuse of Rosemary’s body for their own ends illustrates how these spaces serve patriarchal structures. It’s in “her” domestic space, where both figures control and isolate Rosemary from her friends, seeking knowledge, and her own bodily knowledge. During their first appointment, Dr. Sapersiten, a cult-friend of the Castevets, orders Rosemary not to read books or listen to her friends. When she begins experiencing grueling abdominal pain, Saperstein scolds her for reading a pamphlet on ectopic pregnancy and purposefully misinforms her that the pain is from her pelvis expanding. He continually tells her the pain will subside, but we heartbreakingly watch these hollow reassurances contrast with Rosemary’s sickly decline. After Rosemary tells Guy she’ll be seeking a second opinion from Dr. Hill, her original doctor, he coerces her to not see him. Once she begins to piece together that the Catevests are witches, he also prevents her from seeking knowledge on witchcraft, throwing away the book on witches gifted to her by her friend Hutch. The tannis root necklace gifted by Minnie amplifies these manipulations as its revealed controlling properties allow these deceptions to take hold of Rosemary’s psyche without much resistance. The necklace and its surrounding lies symbolize just how easily dominant cultural ideals control and isolate women from their sense of self.

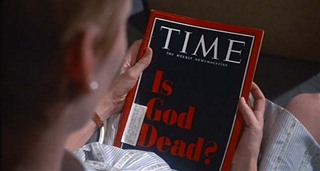

At first glance, the religious cult’s role in the story seems to represent an underlying, 60s cultural fear surrounding the death of God and morality in American culture. It certainly provoked that fear out of some audience members. Ira Levin, author of the book Rosemary’s Baby, recalled, “A woman screamed ‘Blasphemy!’ in the lobby after the first New York preview, and I subsequently received scores of reprimanding letters from Catholic schoolgirls, all worded almost identically.” This is most dramatically emblematized when frightened Rosemary, now piecing together the cult’s plot against her, picks up the issue of Time Magazine titled Is God Dead? while waiting to seek refuge at Saperstein’s office. The article, much like the film, sparked outcry amongst American readers, Time receiving 3,421 angry letters and contributing to countless angry sermons. At face value, the cult thus seems to critique Catholicism and the government from protecting American citizens from the rise of occult groups. An interpretation that Levin himself feared audiences took, contributing to a rise in Christian fundamentalism.

However, the article and its inclusion in the film are much deeper than a direct assault against religion or a provocation of this fear. The article itself is an incredibly nuanced depiction of changing debates in 60s theology. It captures a specific moment in American culture when many people still believed in God, yet, due to political turmoil surrounding the civil rights movement and war, questioned his existence and the church’s power. How could God exist in a world where one’s government inflicts injustice and misery on its citizens? Considering religion and the American government are entwined, the article’s appearance associates the Castevets’ cult, inflictors of injustice, with the American government.

The film visually weaves the cult and Guy into interchangeable figures with each other and the government in the second dream sequence, when Rosemary is drugged. At its beginning, Guy undresses her on a yacht’s top deck with a group of people in attendance, including figures that resemble Jackie and John Kennedy. She later walks through a hallway into the Castevets’ living room to lie down, where she envisions the cult naked as they begin chanting and drawing symbols on her naked body. The inclusion of the Kennedys in this sequence draws a parallel between the government’s invasion of women’s bodies and the cult’s invasion of Rosemary’s. As Guy begins to walk toward her, now tied down, a shadow engulfs and then reveals a morphed version of him. He repeatedly scratches down her sides, each repetition revealing a more feathered, reptilian arm. She looks up at his face to meet the red eyes of a demonic creature who rapes her. She exclaims, “This is no dream! This is really happening!” When Rosemary addresses the scratches, Guy casually states, “I didn’t want to miss baby night.” This sequence entwines Guy and the cult/Satan as one in the same. In the devilish eyes of the patriarchy, her reproductive body is his to use for his career advancement. As the cult represents governmental control over female subjectivity, Guy represents the way those structures bleed into interpersonal relationships.

The film further uses sleeping in an ending scene with Dr. Hill. As Rosemary wakes up to the plot the Catevets’ cult and Guy have played on her, “All of Them Witches. All of Them Witches,” she seeks help from Dr. Hill. He lays her down to rest, promising to take her to the hospital in a few hours, the nightmare seemingly over. However, when she wakes up to Dr. Hill returning, he has notified Dr. Saperstein and Guy, dismissing her concerns as hysteria. Although Hill isn’t with the cult, his actions still serve their agenda. This scene’s stomach-dropping effect emanates from the horrific revelation that patriarchal control seeps into every aspect of life, working on multiple levels to obliterate women’s bodily autonomy.

The most terrifying part about watching this film today is that this horrific feeling is still rooted in the reality that the government still seeks to control women’s bodies and erase our autonomy. After the overturn of Roe v. Wade, Rosemary’s Baby haunted present-day discourse. Film bloggers and content creators resurrected the film as a cautionary tale about the loss of personhood during pregnancy. While women have more rights than they did in the 60s, reproductive rights themselves are vanishing. The hard truth remains that in the eyes of the American government, female subjectivity remains malleable to the changing law and thus threatens to erase our rights entirely. This is the most chilling aspect of the film to me. That the emotions emerging from Rosemary’s slow entrapment, an eerie helplessness and growing distrust, reflect how I’ve felt since the overturn. Just a week ago, the wind practically escaped me when I read the recent article headlines about RFK Jr’s FDA safety review of mifepristone, a widely used and scientifically tested abortion pill. The government instills and impedes through walls I cannot see, I cannot grasp, but continue to close in on me. It produces sensations akin to a nightmare that I can’t claw my way out of. In disbelief, Rosemary’s words echo a dreadful thought that has raced through my mind for the past three years, “This is no dream! This is really happening!” I sit suffocated between the Law on my left and the Fundamentalist Christian on my right in a mute taxi ride towards nowhere I can truly call my own.

Resources:

1. Erin Harrington, Women Monstrosity, and Horror. Routledge, 2019, pp. 87, 102, 106.

Edited by Finn Odum

Interesting that the cis men who place themselves at the front of every screening room with a mic, every curatorial panel, every critical anthology or editorial masthead, are *mysteriously* silent as the grave when it comes to speaking out and doing work to reverse patriarchal violence. Why are our reproductive freedoms and human rights so often relegated to.the realm of “women’s problems,” while they hold forth on politics and culture that we comprise half of? This is a male problem. It belongs to the global overclass of men and their handmaids who remain bystanders (or worse, enablers) to their peers who insist on fully transitioning the US into an evangelical theocracy. Roman Polanski – a rapist – and his cultural disciples might make cool movies, but they are every bit as culpable for the conditions described in this essay as Christian fundamentalists. Nor can we afford to make excuses for “nice” men, the Guys, the “hubbies” who remain neutral while we are stripped of our human rights. So where are the film bros doing the real, hard work of unlearning this sh*t and publishing reviews that stand in solidarity with the Rosemarys…or, more importantly, women and femmes who have none of Rosemary’s privilege?