|Harry Mackin|

The Exorcist plays at the Trylon Cinema from Sunday, October 26 to Sunday, Tuesday, October 28. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

The Exorcist knows you’re afraid of it from the moment it begins. Well before its disturbing supernatural plot starts in earnest, you can feel the malice Friedkin imbues into every shot and frame, like “fear in a handful of dust.”

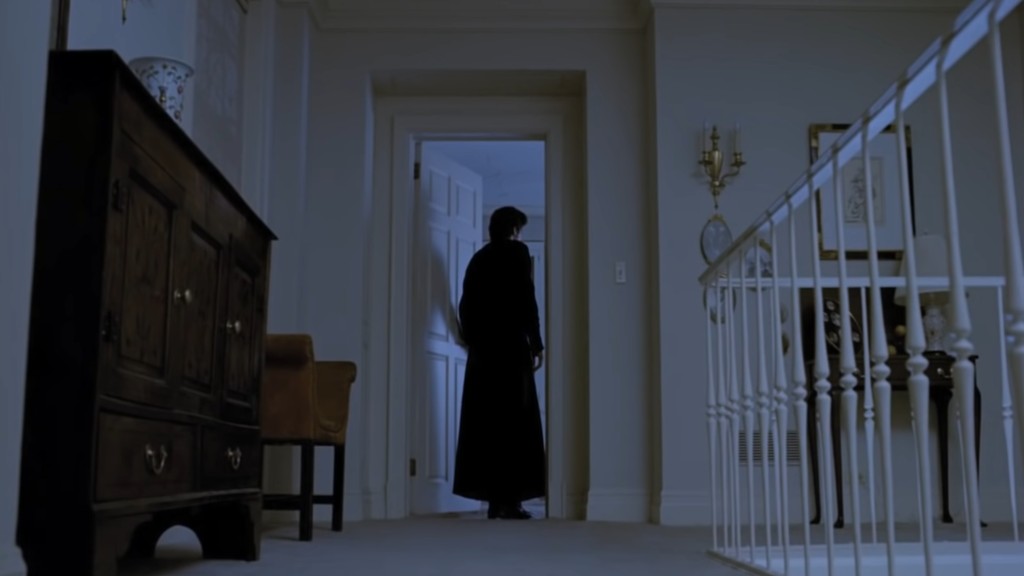

It’s an instantly recognizable kind of shift in your perception. Just a few, largely mundane scenes into The Exorcist, you find yourself searching the corners of the MacNeil house for signs of movement, or second-guessing what you just saw for a frame or two, or wondering about the housekeepers the way you never would in another movie.

The scene that uses “Tubular Bells” is a perfect example. Before anything that could reasonably justify its electric sound and fury, the score plays over a short, largely dialogue-free scene of Ellen Burstyn’s character, Chris, walking home from work. Out of context, you’d never imagine it’s nearly as terrifying as any of the pandemonium unleashed in the film’s latter half. But the anticipation of fear is a kind of fear all its own.

The Exorcist recreates the experience of how fear transforms the world with terrible accuracy. It’s in the way the shadows and the sun dancing on a nun’s habit look sinister or almost darkly prophetic; the way a lived-in kitchen adorned with children’s drawings and art projects suddenly feels alien and oppressive.

It’s a natural sensation to recreate in a film so concerned with religion. I suspect it’s this universal reflex that has always granted Faith its awesome power. At least, that’s how it always was for me. The anticipation of fear played an outsized part in my childhood. From around four to eight, I had debilitating anxiety. It was hard for me to go to school or play with my friends, because something would set me off, and the world would transform into a very scary place.

The biggest fear I grappled with back then was that I wasn’t wrong to feel this anxiety. Even if I understood on some level that I was being irrational, part of my brain couldn’t help but wonder if I was just seeing the world the way it should be seen. It’s the kind of invasive thought that’s too compelling to ignore because you know on some level it has some indisputable merit. Like the titular exorcist Merrin tells Karras about The Devil, “he mixes truth with lies.”

Before I had any other defense against these feelings, I used to pray. I was raised Catholic and, though I was never studious or devout, a child’s version of the religion played a huge part in my life precisely because of my anxiety.

I think this is probably the most honest sort of prayer. It feels like a surrender; an admission that the world is beyond you, that you can’t manage or control it, even that you can’t control your own reactions to it. Maybe there is a power greater than you who can help you.

As I grew up and learned how to manage my anxiety more effectively, I stopped praying. Eventually, I forgot why I ever did it in the first place. That changed just a few years ago, coincidentally around the first time I saw The Exorcist. I prayed for the first time in 15 years, and for largely the same reasons.

It happened when a loved one suddenly, inexplicably ended up in the hospital. We didn’t know what was wrong, only that it was serious. In the hours after, the mind comes to its own conclusions, and not just about what, but about how and why. The scariest parts of The Exorcist are easily the hospital sequences. Anyone who’s ever spent time in a hospital can tell you how unbearable those scenes are, the way Friedkin gets the walls to look right; the way the lighting becomes something evil and mocking. It’s something you take out of a hospital with you, and nothing ever looks quite the same again.

Maybe the hardest part of the scene is Chris’s reaction to watching her child suffer. There’s nothing more impossible to accept than the fact that terrible things happen for no reason at all. There’s no reason why Regan, of all the innocent little girls on Earth, was possessed. There’s no reason why my loved one ended up dying in a hospital. But good luck believing that. I would believe anything else instead, no matter how irrational. And so, the Hell world that invades the minds of anxious little people like me comes back with a vengeance.

The Exorcist is obsessed with the guilt of its characters and what they make this guilt into. Father Karras can’t get over how he wasn’t present for his mother’s death; Chris can’t help but feel responsible on some level for Regan’s condition. The exorcism begins and it transforms not just Regan but everything and everyone around her. Our POV character Chris is confronted with the Hell world that haunted me as a child.

When you’re in the depths of this place, the seductive idea it whispers to you is that there is a reason this is happening. That there is a fate, for you and everyone, written: the world that haunted you as a child has always been the only true world.

The conclusion of this hellish logic is that what’s happening now is your fault. You and your loved ones are condemned to suffer now because you had been hiding from what the world really is, just hoping it would never rear its ugly head in your direction, and your willful ignorance has allowed this to happen. Somehow, Chris and Father Karras’ failures have created the devil that resides in Regan. Somehow, I am at fault for what happened to the loved one I lost.

Chris and Father Karras react to their trial the same way I did—they turn to religion.

It took a tragedy to get me to relate to why people pray again. When you can’t get yourself to see the world as anything other than Hell, you’ll want to believe in anything else instead. You’ll surrender your agency to it just to get the feeling to stop. When my loved one was dying and I could feel the world transforming, I certainly would have made the same bargain. I always thought of this as a kind of failure, until The Exorcist gave me a new way to see it.

God doesn’t beat The Devil in The Exorcist. Karras does. The darkest point in the movie happens when Merrin suffers a heart attack before completing the ritual. The last resort has fallen and it seems evil has won. Karras is at a loss, resting on the staircase outside Regan’s bedroom. Chris, who up until now raged against the inexplicability of the ordeal she was suffering, approaches him with an affect we’d never seen on her before: resignation. She quietly, matter-of-factly asks Karras, “is she going to die?” This simple question finally shocks Karras out of his stupor. He sees in Chris the loss of faith he himself had been grappling with. He knows that if Regan dies, Chris will never leave the Hell he himself failed to transcend.

The way he responds to her is my favorite line reading in the movie: his voice just barely breaks when he resolutely tells her “no.” It’s not something he’s sure of or maybe even something he believes, but it is something he’s determined to make true. It’s this resolution that gives Karras the power to defeat The Devil, not for himself, but for Chris and Regan.

The thing I never fully understood about prayer until The Exorcist is that it isn’t exactly the surrender I thought it was. It’s an act of will, just like Karras’s act when he demands The Devil take him instead of Regan. Even when you can’t help but see the world as Hell, you can still choose to have faith that it’s something else. Karrass’ final act is an act of faith in himself, in Regan, and in Chris: an act of belief that the world can be better than what we see it as. Karras doesn’t believe he can be a savior but he acts as a savior anyway, and in doing so, he becomes one. As he dies, he takes The Devil and the world The Devil whispers with him.

After my loved one died, my failure felt total. It felt like I was being punished for the fact that, for all my efforts, the world has only ever looked like a horror movie to me. But somehow life went on, and I saw The Exorcist, and I found my way back to a world worth living in. Because I learned, like Karras, that faith isn’t about belief, but will. Even if we feel irrevocably irredeemable, we can act as if we aren’t. We can do whatever we have to to believe we can make the world something other than Hell. And if we can keep this kind of faith, maybe our efforts will even be rewarded—if not for us, then maybe for the people we care about most.

I’ll never be a religious person again, but stories like The Exorcist can help me understand a little more about people who are, or at least just help me have a little more faith in those people. The Exorcist accurately recreates the world as it appears when we are overcome by a fear that seems impossibly larger than us, and then it shows us a way to respond to that world. No matter how indisputably the world seems to look like a horror movie to me—and no matter how I convince myself I deserve to live in that movie—I can choose to have faith that it could be something else. I can choose to use that faith to try to make it something else, for me and all the other people I want to believe in, whether I can make myself feel that belief or not.

Edited by Finn Odum