|Finn Odum|

Nixonland plays all October long at the Trylon Cinema, featuring special restorations and glorious 35mm prints. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

I must admit to you that I know very little about the 1970s.

I know that Richard Nixon “pledged to end the Vietnam War”, sending the poorest of America’s sons to die aimless deaths while massacring innocents. Black activists fought in memory of assassinated leaders, while youth protest movements bubbled up on college campuses and demanded we pull out of Vietnam. Salvador Allende was about to be booted out of Chile in favor of a raging fascist, American women were on their second wave of feminism, and my mother was growing up in 70s San Francisco.

I also know about the new MPAA rating system, which expanded what directors could depict on camera. The introduction of age-gated ratings (designed to protect children or something) provided space for more “extreme” film content; with new ratings, filmmakers could push moral boundaries for uniquely adult audiences. Not to beat the The American Family is Dying, Anyway dead horse, but this was one of the most important decisions in American film history. It allowed both experienced auteurs and hot-blooded first-timers to push the boundaries of acceptable art. A young Wheaton College graduate, for example, spent the bulk of 71 working on what started as his porn directorial debut and ended as the excessively violent and subtly comedic The Last House on the Left (kickstarting one of the most influential horror careers of the twentieth century). The same year Last House was released, Trylon all-timer John Waters finished the shock film Pink Flamingos, and Frank Perry adapted a Joan Didion script into the haunting and Finn-traumatizing Play it as it Lays. Artists were not pulling punches. We had officially entered Nixonland.

Featured film: Kuroneko

Blood on the White Picket Fence

Nixonland: Horror in the Vietnam Era highlights a host of incredible films, including some of the biggest “anti-family” hits. The American Dream was crumbling; counterculture movements were changing family power dynamics, while the Vietnam War robbed parents of their children in the blink of an eye. At the Trylon, we’re kicking off the month with The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, depicting one of the original deconstructed horror families. If you’re lucky, you’ll also catch Deathdream, a.k.a Dead of Night, a.k.a Bob Clark’s pre-Black Christmas Vietnam zombie movie. Relatively underseen, Deathdream destroys its central family by confronting the little-understood concept of PTSD, as well as the impact of addiction on families.1

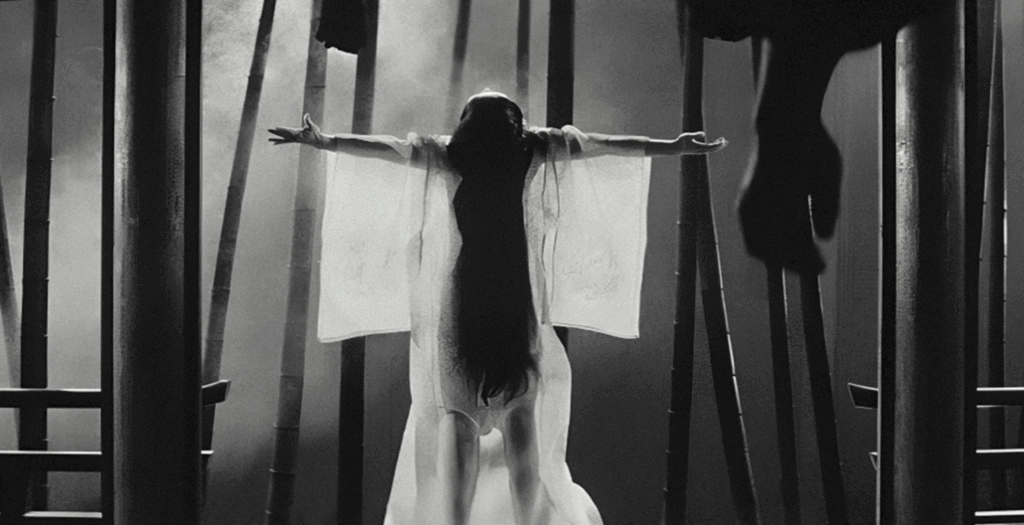

It would be a mistake to exclude some of the incredible international horror that came out during Nixon’s presidency, particularly as the investigation of familial implosion was blossoming both within and outside of the United States. Kuroneko allows us a glimpse into feudal Japan and the relationship between a mother and her daughter-in-law after a violent encounter. It centers their relationship with war as well; much like writer/director Kaneto Shindō’s Onibaba, Kuroneko dismantles the patriarchal Japanese family and gives power to the women, those who are often the victims that war leaves behind.

Seventies-era Family Deconstruction goes beyond what our series includes (because we can’t just program everything I want us to, obviously). You have Bleak Week 2025 pick Natural Enemies, Wes Craven’s classic The Hills Have Eyes, and Brian De Palma’s Sisters. If you enjoy what we’ve included here, I’d recommend Ordinary People, Dogtooth, Speak No Evil (2022), and Crocodile Tears, the last of which I was lucky enough to see at MSPIFF earlier this year.

Featured film: Black Christmas

The Specter of Social Equality

Destroying the traditional family was (and still is) a fear for conservative politicians. The next scariest thing they can think of? Giving equal rights to people of color and women.

The 1970s were a breakthrough era for Black representation in film, both in terms of starring roles and creative direction. Early films reflected the Civil Rights Movement, portraying the fight for equality through cinematic horror. Blaxploitation movies allowed Black actors to fight against white supremacists, backed by iconic soundtracks reflective of the growing funk, soul, and jazz movements. Scream, Blacula, Scream is our Blaxploitation pick for the series, and stars William H. Marshall—an absolute icon, mind you, whose acting encompassed TV, film, and opera. We’re also featuring Night of the Living Dead (alongside previous entry Deathdream), which, upon release in 1968, included one of the first Black horror protagonists in Duane Jones’s Ben.

Second-wave feminist movements were also growing during Nixon’s presidency, this time focusing more on a woman’s right to her bodily autonomy. In 1973, Roe v. Wade legalized abortion in the United States, much to the disappointment of violent misogynists and religious extremists everywhere. In 1974, Bob Clark released the genre-defining Black Christmas, taking the fresh stance that women should be allowed to have a safe abortion (wild!).2 Films like our other series opener, The Stepford Wives, highlight the inherent sexism of gender roles and the male desire to hold power over women. Others discuss gaslighting, isolation, and other forms of mistreatment women can experience when in crisis. Check out Let’s Scare Jessica to Death, a film with a title inviting its audience to question the intentions of everyone in the film.

Given the nature of Nixon’s regime, it’s hard to narrow down just a few great social issue horror movies. There’s the original Blacula and the Black vampire classic Ganja & Hess, the latter of which also stars Duane Jones. Movies like Vampyr Lesbos give women control of their own sexuality, while Carnival of Souls studies female isolation and mental anguish in the wake of tragedy. If you want to look beyond what the Nixon era offers, I recommend the 2020s era films They Cloned Tyrone, Resurrection, and Huesera: The Bone Woman; the first is an underseen Black sci-fi/horror banger, and the latter two focus on uneven gender dynamics and a woman’s bodily autonomy.

Featured film: this is just what Finn gets up to on the weekend with their pagan friends.

God, What Have I Done?

I know at least one reader looked at my previous section and asked, “Okay, loser, where’s Rosemary’s Baby?”

In the midst of the Vietnam War and the growth of countercultural movements, a Christian faction known as “Jesus People” began to soil themselves at the sight of (gasp) women without husbands. The Evangelical movement was led by individuals like Baptist Billy Graham, who thought the woman’s role was in the kitchen and that gay people were mentally ill. This is where we find Rosemary’s Baby, a representation of religion forcing a woman to conform to their views (and directed by a predator). The rise in Christian extremism contrasted with its disillusioned youth, many of them who suffered from trauma enacted by the church. The cult at the center of The Wicker Man is both a reflection of Christianity’s fear of the unknown and a pagan allegory for Christians. The Exorcist, a very literal depiction of how “demons” can destroy a family, reminds me of how it felt to be a twelve-year-old at church camp, where four twenty-something-year-olds are praying over you at full volume.

The Christians were afraid of a lot of things: gay people, women’s rights, Middle Eastern Jesus (to name a few). The burgeoning “sexual revolution” caused most of these concerns. ‘70s exploitation films (like The Last House on the Left) worked overtime to scare Evangelicals, depicting the limits of human sexuality and the depths of depravity. Other thriller-dramas took a softer but still unsettling approach: Ingmar Bergman’s The Hour of the Wolf, one of our few international picks, uses monsters to convey issues of sexuality and identity. His obsession with his demons leads to the dissolution of his marriage—violently, consuming him entirely and leaving his wife scarred.

Religious horror (and horror about the sexuality those conservatives fear) is not uber unique to the seventies, though it does reflect a spiritual turn in mainstream American culture. Since The Exorcist, we’ve had dozens of mild-to-monumental demon movies. To my dismay, we’re not showing my favorite religious ‘70s horror, The Omen. If you’ve seen that already and want something perhaps more off-key, consider Penda’s Fen. The Iron Rose falls a bit more in line with The Hour of the Wolf, but provides a more unhinged, more French look into the depths of sexual delusion. For modern (pseudo) sequels, viewers can’t go wrong with 2016’s The Wailing (shown at the Trylon last fall), or Saint Maud, Apostle, and The First Omen.

Finn’s America, 2025

Sometimes, when I choose to have hope that the Trylon will be here in a hundred years, I wonder what the “Trump’s America” horror series will look like. I don’t know if it will be able to capture the nonfiction terror that I and many of my loved ones are experiencing right now; it is one thing to watch Daniel Kaluuya almost lose his brain to a white supremacist cult in Get Out, and an entirely different thing to, in real time, watch citizens get abducted off the streets by ICE. Just recently, a professor from Oxford predicted that the United States had 400 days to course-correct before spiraling into utter destruction. A horrifying concept that has absolutely happened to a host of other countries, many of which were devastated by U.S.-funded political regimes.

Our present is another culture’s history crossed with the worst of the Hunger Games, and I’m still expected to get up and manage digital advertisements every morning.

Although I believe it’s slowly losing its merit, there is something beneficial about consuming cathartic media. For a moment, we’re reminded that our fears are not unique. We are not alone, because this has happened before. And not only has it happened before, it’s been documented, filmed, painted. Cemented in the ink of books that they’re bound to start burning, but still passed down in defiance by word of mouth.

We need to fight for our present and the Earth’s future. There’s a lot we can learn from our past to inform ourselves.

Let’s (re)visit Nixonland, together.

Footnotes

1 If you miss our 16mm screening of Deathdream, it is free to stream on Tubi! Olga also read that and then asked me if I’m an agent for Tubi. I am not, I’m just a fan of free film streaming opportunities.

2 I wrote an essay about BC and its impact on horror in 2019. It’s fine. There’s a map.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon