|Dan McCabe|

The Stepford Wives plays in glorious 35mm at the Trylon Cinema on Friday, October 3 to Sunday, October 5. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

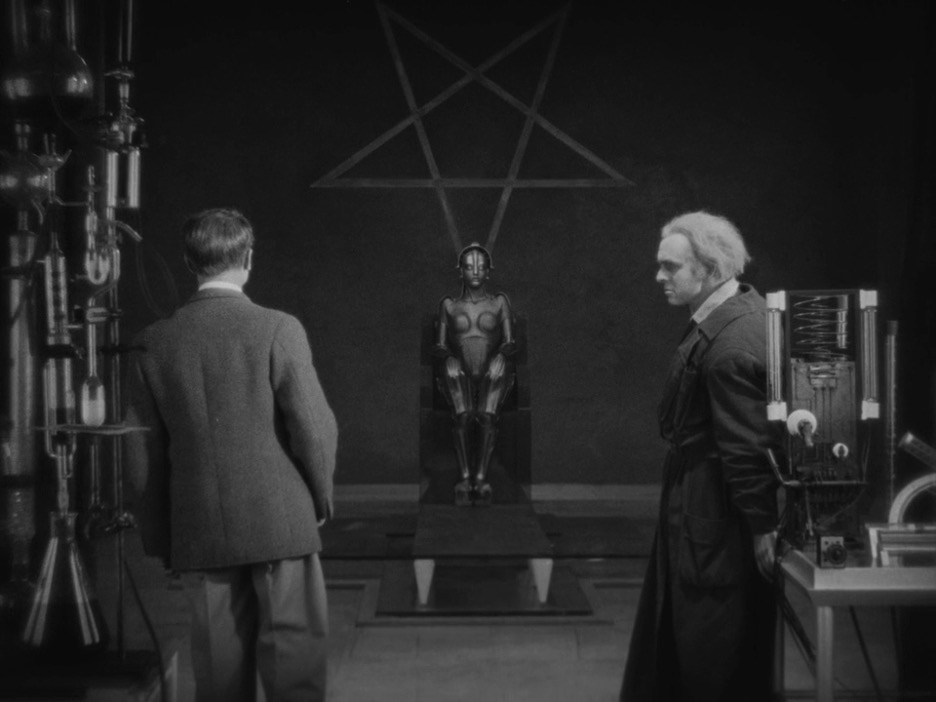

“She is the most perfect and most obedient tool which mankind ever possessed!”

– Rotwang upon revealing the Maschinenmensch in Metropolis (1927)

Obedient tool. That phrase from the intertitles of Metropolis describes what a group of men desire in another science fiction film made decades later, The Stepford Wives (1975). In Metropolis, the mad scientist Rotwang (Rudolf Klein-Rogge) created the Maschinenmensch, a robot built solely to destroy his enemy, Joh Fredersen (Alfred Abel). Needing a human face to copy onto the robot, Rotwang dehumanizes Maria (Brigitte Helm) by stealing her likeness and transferring it to his evil automaton.

The men in The Stepford Wives had an even more nefarious scheme in mind. But before we go on, I’m going to describe plot points from The Stepford Wives in this article, as well as the films Metropolis and Ruby Sparks (2012). If you haven’t seen these movies and you want to see them without spoilers, feel free to stop here.

The reveal at the end of The Stepford Wives has become well-known in popular culture, but in case you’re unfamiliar, the men of Stepford systematically kill their wives and replace them with robots. Despite the famous ending, The Stepford Wives is not a film about technology. Substitute in hypnosis, drugs, blackmail, magic, or any other trope standing in for methods of control, and you have the same film. It has little in common with films that are squarely about robotics, such as Blade Runner (1982).

The Stepford Wives is not a particularly deep exploration of gender roles, either, despite itself. It contains cursory mentions of Second-Wave Feminism (referred to as “women’s lib” in the film), and the robot-obsessed men are certainly enforcing a brutal patriarchy. But it goes no deeper than this. The references to Johnna’s social consciousness are cursory, and the film’s pace has little time to explore them. A relentless suspense carries the film forward, in this case, the psychological terror of Johanna’s experience: knowing that something is terribly wrong in Stepford but not knowing exactly what. The plot-train has little time to stop and explore Johanna’s personal views or the society around her.

The film fails to examine patriarchy beyond presenting some of the most easily detestable men-in-power ever committed to celluloid. The Stepford men are monsters: purely one-dimensional mustache-twirlers. For example, just before Johanna is killed by the robot that will replace her, the emotionless inventor Diz (Patrick O’Neal) gives a monologue that would make a Bond villain proud. The film spends no time on his motivations or broader societal structures, nor does it answer why an expensive scheme to replace women with robots makes more sense than divorce and hiring servants.

Even so, The Stepford Wives turned my thoughts to two other films that delve more deeply into the themes of technological control and gender roles. These are Metropolis, perhaps the first great science fiction film; and Ruby Sparks (2012), a lesser-known romantic comedy from this century.

Unlike The Stepford Wives, Metropolis is squarely a film about technology. You could not replace the enormous machines in Fritz Lang’s imaginary city with another stand-in, like you can with the robots at the end of The Stepford Wives. The entire thematic foundation of the film would collapse. A good example of this observation comes from the scene most similar to the ending of The Stepford Wives.

The mad scientist Rotwang creates his robot to destroy Joh Fredersen out of jealousy. Rotwang loved Fredersen’s deceased wife, Hel. The fact that Hel chose Fredersen over Rotwang drives him mad.

He kidnaps Maria because she had gained the loyalty of the workers of Metropolis’s depths. When he replicates her face and voice and gives them to the robot, Rotwang can manipulate the workers’ anger. To the workers, the person telling them to destroy the city is not the soulless Maschinenmensch, but their trusted leader, Maria.

One could not substitute the robotics in this scene with another trope and retain the same meaning, like you could at the end of The Stepford Wives. If the “false Maria” were a brainwashed version of Maria, or a magical being, the thematic structure of the film would fall apart. Director Fritz Lang’s theme is that advances in technology create structures of control that dehumanize people in each other’s eyes, and only by bringing people back together can you re-humanize them. “The heart is the mediator between the head and hands” is a corny tagline (Fritz Lang certainly thought so), but it exists to criticize systems of control where it’s the “head” above crushing the “hands” underneath.

The Stepford Wives has patriarchal expectations and insecurities crushing the humanity of the women of Stepford. Yet they do so in absentia. Much of what drives the film revolves around Johanna’s lack of knowledge about what the men do behind the scenes. In Metropolis, Fritz Lang gives us unforgettable images such as Freder’s (Gustav Fröhlich) vision of the Heart Machine transforming into a monster devouring the workers of the city’s depths. Metropolis puts themes of technology and control at the forefront. The Stepford Wives does not.

While The Stepford Wives touches upon commentary on the Second Wave Feminism of the 1970s and the backlash to it, it is always a thriller first, and a social commentary second. Ruby Sparks comes to mind as a better examination of gender roles, although it comes from a different era. It uses magical realism to tell the story of a man who creates a woman to end his loneliness and satisfy his desires, without regard to her emerging humanity.

Calvin Weir-Fields (Paul Dano) writes his ideal woman, Ruby Sparks (Zoe Kazan, who also wrote the screenplay), into existence. The film plays on the trope of the “manic pixie dream girl” which popped up in the films of the 2000s and 2010s. Calvin thinks he has solved his writer’s block and loneliness through his godlike ability to create such a woman, like Athena breaking through the mind of Zeus.

Whenever Calvin writes about Ruby, he exercises control over her. At first, the film is a straightforward romantic comedy, until Calvin becomes jealous of Ruby’s increasing hesitance to conform to Calvin’s will. To Calvin, Ruby is his creation, created just for him, to satisfy his desires. He’d fit in well in Stepford.

As the film progresses, Calvin attempts to exercise more control over Ruby. He quickly moves to limit her independence and resistance. “She wasn’t happy. So I made her happy… and now she’s like this all the time,” he says at one point, as if the source of her unhappiness was something superficial and not Calvin’s desire to keep her in the “perfect woman” box he’s built for her.

At the end of the film, Calvin becomes so angry at Ruby’s increasing individuality that he writes her into his personal marionette. She says things that Calvin wants to hear, at one point repeating “You’re a genius, you’re a genius.” Ruby looks horrified when Calvin exercises this humiliating control over her. She eventually escapes from him and locks herself in the bathroom. Calvin, shocked at his own monstrous actions, writes Ruby as free from his control. Unlike the men of Stepford, he sees the abyss in front of him. Instead of destroying Ruby’s humanity, Calvin takes the opposite approach and takes himself out of her life.

Ruby Sparks is entirely about a man controlling a woman for selfish purposes, failing to see her individuality as anything other than a nuisance to edit out of her. What separates it from The Stepford Wives as a more effective examination of patriarchy and constraining gender roles is its genre. As a romantic comedy, it can fully explore the relationship between a man and a woman and their respective gender role expectations of their era, in this case, the early 2010s. The Stepford Wives provides very little insight into Johanna’s relationship with Walter (Peter Masterson); we only see gaslighting provided by a stock villain. There’s not much examination of their interactions beyond what is needed to fulfill the thriller’s need for suspense.

So, if The Stepford Wives is not a deep analysis of technology or gender roles in society, what is it? I would argue that it is a quintessential example of thrillers of the 1970s. Like Soylent Green (1973), it has a shocking twist ending. Like The French Connection (1971), everything about the set design and costuming transports modern audiences to a decade fifty years in the past. Its impact as a thriller stands the test of time.

Edited by Finn Odum