|Sophie Durbin|

Rosemary’s Baby plays in glorious 35mm at the Trylon Cinema from Sunday, October 12 to Tuesday, October 14. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

“I could imagine only two possibilities: my unfortunate heroine had to be impregnated either by an extraterrestrial or the devil.” (Ira Levin, author of Rosemary’s Baby)1

I take so much pleasure in every rewatch of Rosemary’s Baby that it often feels more like I’m visiting old friends, not watching one of the scariest films of the twentieth century. I love the pink font used in the title sequence, the New York Christmas scenes, the way Roman Castavet repeats the phrase “You name a place, and I’ve been there,” Ruth Gordon’s outfits, and the Dakota building apartment even after Rosemary ruins all the wood with her trendy yellow decor. This fondness poses the threat of taking the edge off the film. Recently, in an attempt to re-encounter Rosemary’s Baby as the horror classic that it is, I thought back to my first viewing: which scene was most unnerving back then, when it was all new to me? The answer is a bit of an Occam’s razor: the most perfect scene within this perfect film is Rosemary’s dream sequence, during which she is impregnated by Satan himself in a ritual ceremony with the works: chanting, weird nudity, and perverse references to Catholicism. What did Polanski draw from to make this scene so harrowing, and how does it fit into broader historical narratives around satanic ritual? These are the research questions I am here to investigate today as we enter horror movie season, and in doing so, I hope to find new things to be spooked by when I’m greeted once more by Rosemary and friends on the Trylon screen.2

It’s important to start by remembering that Polanski was always-and-already a master of eerie dream sequences by the time he adapted Ira Levin’s novel for film. Dreams are important across Polanski’s entire “Apartment Trilogy,” of which Rosemary’s Baby is the second installment alongside Repulsion and The Tenant. In all three films, the characters experience dreams or dreamlike states where little mundane details from waking life become uncanny and horrifying, and which foreshadow the eventual deterioration of their mental states. In Repulsion, Catherine Deneuve fixates on a crack in a sidewalk which later appears in her apartment walls; in The Tenant, Roman Polanski peers at his own image through binoculars across a courtyard, hinting at his eventual total loss of self. The Rosemary’s Baby dream sequence is the most true to how dreams really play out for most of us. The narrative arc is illogical, the timing anachronic. Rosemary slips from one setting to the next, as if it’s the most natural thing in the world. She is at once in bed, floating at sea on a raft, above and below deck on a ship, and strapped to a platform in a dungeonlike chamber with ceilings reminiscent of Italian frescoes.3 We see the apartment elevator operator reappear as the ship’s first mate, and Rosemary’s friend Hutch becomes a weatherman. Guy’s fingernails are Satan’s claws as Rosemary is violated in both the real world and her dreamscape. The dream is flecked with moments of embarrassment and shame, so common in dreamland: Rosemary tries to cover her naked body on the ship’s upper deck as she is undressed at the same time in her bed. In the screenplay, it is made clear that she is climaxing at the moment that the Pope enters, and that she attempts to hide this from him; her indignity makes sense, since we know she was raised Catholic. The pope’s doctorlike manner reminds us of the two doctors who will later betray her. Every component of Rosemary’s dream has a typological equivalent in reality.

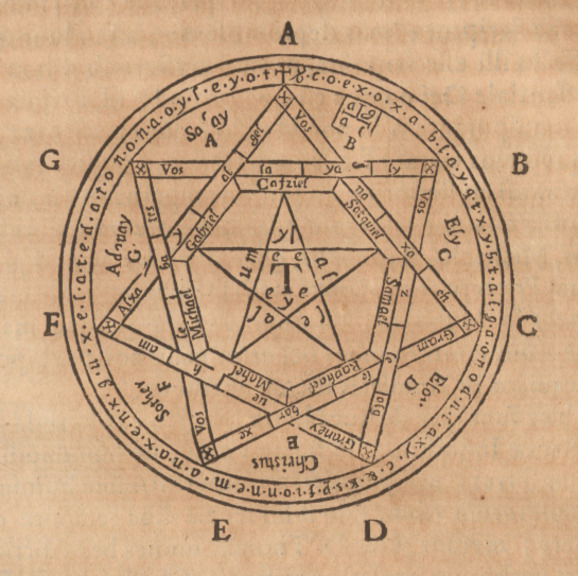

So, we’ve clarified that the dream sequence itself is expertly crafted. How does the Satanic component of the dream play out? Similarly to how Dracula adaptations have themselves constructed much of the vampire lore that we now hold to be ancient and self-evident,4 Satanic activity in movies has a lot more to do with what writers and directors have come up with in their wild imaginations than any provable traces of real-world practices. Intriguingly, Polanski chooses to only show bits and pieces of the demonic rite. Rosemary’s torso is painted with red symbols but we don’t see them fully. We only see the yellow eyes, claws, and reptilian back of the beast that mounts her. Naked members of the coven surround Rosemary, but the meaning of their chanting is never explained, nor is their nudity. This makes the impregnation ritual and its aftermath (think of the tannis root necklace and nasty herbal drink that Minnie Castavet gives Rosemary) unnerving precisely because we don’t quite understand it. The coven itself is mostly obscure to us throughout the film aside from a few lurid details that Rosemary pieces together, such as the importance of baby’s blood in the witches’ sabbaths. Some of these ideas Levin likely pulled from the Renaissance-era treatise on witchcraft called the Malleus Maleficarum, which introduced the concept of witchcraft as an organized satanic cult. Significantly, the Maleficarum describes discrete groups of witches who consort with Satan and go about it by carrying out certain sacraments. Other early grimoires of the occult, like The Sworn Book of Honorius, are likely a strong influence on the design and aesthetics of magic books on film such as All of Them Witches, the book Hutch leaves Rosemary which leads to her revelations about the Castavets. Here, we’re given a witch cult that is mysterious, yet fully-formed and creepily credible—it even has its own history book.

Polanski made Rosemary’s Baby when Satan was having a chic moment among those in the know: see Kenneth Anger’s Scorpio Rising and the interest in occult leader Aleister Crowley across 1960s counterculture. Through the rise of modern Wicca in Britain in the 1960s, witchcraft was also being re-conceived in the public eye as something everyday people might partake in, with the idea of witches lurking in a New York brownstone not so far-fetched.5 With Rosemary’s Baby’s distinctive urban setting, Polanski made way for a whole decade of Satan-in-the-city horror such as The Exorcist and The Omen, along with smaller-scale oddities like The Sentinel. But Polanski’s coven of witches is distinctive because they are very funny and very New York, and their sinister intentions are at first hidden behind this affable veneer. This is particularly clear in the dream sequence, when the dissonant chanting is memorably juxtaposed with Minnie barking out instructions in her honking voice. The whole dream, in fact, is pure New York. The pope’s appearance isn’t just a reference to Rosemary’s Catholic upbringing: it also recalls Pope Paul VI’s visit to New York on October 4, 1965—which Ira Levin cites as the baby’s conception date.6

Eventually, Satanic ritual on film transitioned from avant-garde and daring to passé. An accidental outcome of Rosemary’s Satanic impregnation scene was its influence on the Satanic Panic of the 1980s, a mass hysteria surrounding thousands of unproven cases of satanic ritual violence. In many cases, accused individuals lost their jobs or their reputations. Gay daycare workers were targeted in particular, possibly due to mass anxiety over children being taken care of outside the home while their mothers went to work, or an unfounded obsession with pedophilic cabals which we have now seen play out again in the QAnon phenomenon. Supposed victims of ritual abuse often recalled scenes seemingly lifted directly from Rosemary’s Baby.7 The credibility which Polanski and Levin built through the scene’s intricate setup was, apparently, done too well. Ironically, Rosemary’s story, unlike the Satanic Panic phenomenon, squarely casts blame for Rosemary’s predicament on her social circle, who she is meant to trust. She’s not being defiled by convenient scapegoats, but by her doctors, her husband, and her neighbors. That her ordeal had real-world consequences that run so counter to Levin’s message may be the true lasting horror of the film.

Notes:

- The Criterion Collection. “‘Stuck with Satan’: Ira Levin on the Origins of Rosemary’s Baby.” https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/2541–stuck-with-satan-ira-levin-on-the-origins-of-rosemary-s-baby. ↩︎

- I’m actually already spooked as I write this in a tiny hotel room in Cannareggio, Venice, where I just made my way back to my room through a series of creepy tiny streets. I have the movie up in case I need it, but I also have a PDF of the screenplay open in another tab because the silent nighttime Venice vibes are making it hard to casually watch any of the movie without being afraid I’ll have trouble sleeping later. ↩︎

- Polanski’s screenplay describes the chamber walls/ceiling as also reminiscent of the creepy linen cupboard at the end of the hallway that covers the secret passage to the Castavets’ apartment, which I had never noticed. ↩︎

- See my The Keep article from last month for more on Dracula lore! ↩︎

- Note that Rosemary refers to witches’ esbats, the term for a non-sabbath coven meeting in modern Wicca coined by Margaret Murray, whose witch-cult thesis was influential on Gardner. ↩︎

- Levin kept track of New York newspaper headlines all through the writing process of the novel, carefully weaving Rosemary’s journey into the current news of the time. ↩︎

- Laycock, Joseph P. “Satanic Panic.” In Satanism. Elements in New Religious Movements (Online Ed.). Cambridge University Press, 2023. ↩︎

Edited by Finn Odum