|Matthew Tchepikova-Treon|

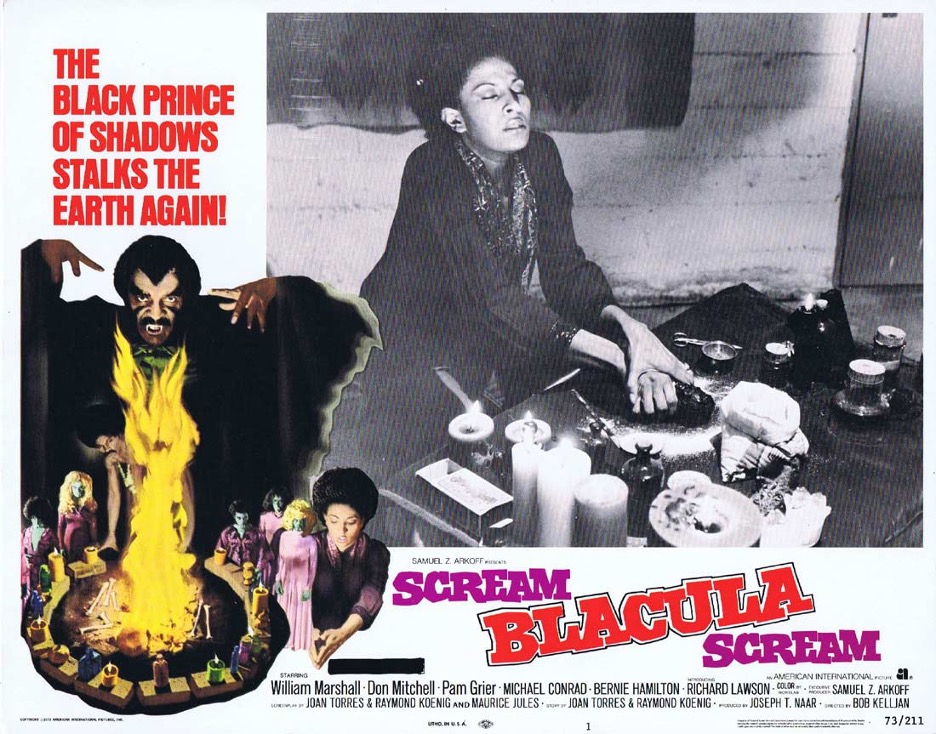

Scream Blacula Scream plays in glorious 35mm at the Trylon Cinema from Sunday, October 12 to Tuesday, October 14. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

1

The following assertion is perhaps already an old saw by now, but still I think it bears repeating from time to time: The notion of “elevated horror” is pretentious AF. It’s a crass moniker meant to distinguish horror cinema’s more prestigious vendibles from an otherwise based genre, conferring legitimacy upon the former by degrading the latter. It’s a cheap marketing stratagem. And it’s an expedient shorthand used to rationalize critical and financial success by declaring, “This isn’t really horror.” It’s also just lazy nomenclaturism.

Elevateds are increasingly characterized by the following equation:

Psychological Unease + Raw Social Commentary × Deliberate Arthouse Aesthetics ÷ √Letterboxd Hype = Worthy of Critical Attention

This function has served to sanitize prestige horror films for broader consumption. Elevateds are, thus, typically embraced by mainstream critics and awards bodies that might otherwise dismiss the genre whole-cloth, despite its sustained presence as an artistic and economic engine within American cinema for over a century. In doing so, this rhetorical maneuver devalues the very genre-base that provides Elevateds the foundation for their critical and financial success. More insidiously, it strips horror of its own history.

2

With that out of the way for now, let’s talk about Blacula and its cursed progeny. The film’s title isn’t just a fantastically clever name; this isn’t just black Dracula (in the vein of 1973’s Blackenstein, a swing-n-miss attempt to ride Blacula’s leather coattails with little to recommend it). Instead, the name Blacula is a cipher that transforms the subgenre’s central mythos of bloodsucking from Gothic fantasy into a direct commentary on the real history of chattel violence. The central premise: an eighteenth-century African leader, Prince Mamuwalde, is vampirized by Count Dracula after asking the Victorian noble to help put an end to the Transatlantic Slave Trade. Equal parts appalled and wickedly amused at Mamuwalde’s request, the count assaults his wife, bites his neck, and seals him in a crypt, eternally cursed by the white hand of European aristocracy and soon to be loosed upon a new country built on the theft of over 4 million bodies.

The film then drags its regal vampire, coffin and all, to Los Angeles circa 1972. Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Songwould’ve still been in theaters, alongside Shaft, Super Fly, and Trouble Man. Accordingly, with Blacula, American International Pictures tapped directly into blaxploitation cinema’s high-style, low-rent aesthetic near the peak of its cultural powers. And while Blacula wasn’t the first cinematic assertion of black horror—that honor goes to The Dungeon, made by silent-era auteur Oscar Micheaux in 1922—director William Crain’s blaxploitation gamble paid off at the box-office, momentarily expanding black horror’s industrial horizons.

But the twenty-three-year-old filmmaker from UCLA wasn’t slumming it with Blacula, as numerous accounts have suggested given his proximity to the L.A. Rebellion film movement. Just as Isaac Hayes, Curtis Mayfield, and Marvin Gaye weren’t slumming it when they recorded their game-changing soundtracks for Shaft, Super Fly, and Trouble Man, respectively. They were expanding black popular music’s cultural+industrial reach into new spaces, new forms. Composer Gene Page’s score for Blacula did the same. Along with directors Gordon Parks and his son, Crain recognized that, for black artists, exploitation cinema was a side door to the American film industry that audiences had just pried wide open.

Admittedly, Blacula’s small budget often struggles to match the movie’s big ideas. It has a choppy plot, bad lighting, cheap special effects, and rubber bats on strings, but it also has William Marshall, the Broadway performer and onetime Boris Karloff understudy. Sure, at times it can feel like listening to Othello recite a telemarketing script, but I disagree with the many contemporaneous reviews of both Blacula and Scream Blacula Scream that repeatedly commented on how the classically trained actor was overqualified for an exploitation picture. He, too, was not slumming it. Possessed of a voice that sounds like a velvet-draped mausoleum, Marshall plays Blacula with an astounding, meticulous Shakespearean gravitas, treating the plot as a sustained existential tragedy. That’s because Blacula has no obligation to transcend its drive-in lineage in order to be worthy of the pathos Marshall generates. The discordance is part of the fun; it might even be part of the point.

1a

Claims about horror’s current elevation aren’t totally new. As dusk settled on the 2000s, variants of the term were already creeping around. Films like Ti West’s satanic-panic throwback, The House of the Devil (2009), with its slow-burn suspense and video store stylings, sparked a fair amount of “return-to-glory-days” mumbling, while also setting the stage for a cycle of truly innovative entries, such as A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night, The Babadook, and the immaculate It Follows, all in 2014. That same year, even less splashy entries like Goodnight Mommy, Creep, and Starry Eyes suggested momentum from the margins. But the true ascendence of Elevateds dawned with the holy trinity of Robert Eggers’s The Witch (2015), Jordan Peele’s Get Out (2017), and Ari Aster’s Hereditary (2018), rightly accorded widespread acclaim for their formal inventiveness and provocative examinations of religious fanaticism, “post-racial” racism, and familial dysfunction. They also made bank at the box-office.

Follow-ups from Peele, in particular, heralded a “Black Horror Renaissance,” including Misha Green’s Lovecraft Country, Remi Weekes’s His House (2020), Nia DaCosta’s continuation of Candyman’s story in 2021, the animated horror romp Wendell & Wild (2022), and of course Sinners (2025). From shadow puppetry to blues music’s recurring use of deal-with-the-devil and hell hound imagery, these shows and movies themselves tell layered stories about black horror’s deep history across artistic forms.

Indeed, black horror cinema has long shared cultural ground with black music. Seminal works from the 1990s gave bold expression to this artistic consortium. Especially the year 1995. In that year alone, we got the Tales From the Hoodanthology, produced by Monty Ross and Spike Lee’s 40 Acres and a Mule Filmworks company, with music from Wu-Tang and horrorcore rap tracks such as “From the Dark Side” by the Gravediggaz, Bokie Loc’s “Death Represents My Hood,” and “The Grave” by N.G.N. and K-illa. Legendary cinematographer Ernest Dickerson also directed the Tales From the Crypt property, Demon Knight, with a mashup of rap and rock, again with Gravediggaz on the soundtrack. (Vampire In Brooklyn also existed.)

As if forged in this multimedia firmament, Cleveland’s hometown rap heroes, Bone Thugs-n-Harmony, also released their 1995 debut album, E. 1999 Eternal. When I was in middle school, already horror obsessed, my friends and I passed a CD copy of E. 1999 back and forth like some occult object, so pleasantly frightened by its pitchshifted vocal incantations of “Mr. Quija” and “Mo’murda.” On tracks like “Down ’71 (The Gateway)” and “Shotz to Tha Double Glock,” the group’s signature slasher-core piano and buzzy synth lines sounded as much like John Carpenter movies to us as they did Westcoast G-funk from the radio. It was quite unsettling and we loved it. (Note to any kids reading this: Get yourself an older sibling with cool older friends who can slide you cool shit from the adult world just a little too early, it’ll pay lifelong cultural dividends, and not even the World Wide Web can compete.) Years later, in college while working as a music journalist for a local magazine, I interviewed group member Flesh-n-Bone over the phone before a tour. We ended up talking horror almost as much as hip-hop as he described the group’s young influences and I shared my many enthusiasms.

Near the end of the 1990s, Blade (1998) took vampires, hip-hop, and electronic dance music and added comic books to the mix. (The “blood rave” is eternal.) At the turn of the century, Dickerson, again, made Bones (2001) with Snoop Dogg, a much maligned musical love letter to 1970s blaxploitation horror.

The above historical snapshots alone show why any suggestion that black horror films have only recently acquired the capacity for sophisticated thematic articulation operates on a flawed fiction. Simply put, it’s an ahistorical lapse, a form of cultural forgetting that happens over and over again. This peculiar need to affix an adjective of respectability to horror dismisses the genre’s vast, messy corpus. It also necessitates a tacit disdain for predecessors like Blacula and Scream Blacula Scream as merely “low-brow,” as if that means they have nothing to say.

2a

In Scream Blacula Scream, Prince Mamuwalde is again resurrected in L.A., again cursed into undeath via a botched ritual performed by a disgruntled Voudon cultist who soon finds two fangs in his throat and becomes a nocturnal blood-drinking monster himself. It’s 1973. Black Caesar, Cleopatra Jones, The Mack, Shaft in Africa, Hell Up in Harlem, and Coffy are all now playing in theaters, as is Bill Gunn’s (retro-elevated) vampire film, Ganja & Hess. Blacula’s sequel indeed functions as a piece of mandatory blaxploitation fare cashing in with more cheap thrills, more martial arts, and more rubber bats. There’s also the odd choice to forgo Gene Page’s funk score-stylings from the original and instead employ composer Bill Marx, the adopted son of Classical Hollywood icons Harpo Marx and Susan Fleming, resulting in a more restrained, yet also somewhat stranger, soundtrack. The film’s undisputed highlight is Pam Grier and her performance as Lisa, the Voudon priestess.

Throughout the film, Marshall’s melancholy grandeur is set against Grier’s cool resilience. Likewise, her character provides a spiritual counterpoint to the inherited, European curse of vampirism. On the surface, this all allows for a riotous, absurd mix of gothic horror, colorful vinyl interiors, afro-diasporic iconography, polyester suits, and African antiquity steeped in blaxploitation sheen. Variations of this particular alloy were definitely en vogue at the time, from Richard Pryor’s early comedy records to Miles Davis’s avant-funk LPs and the movies of Melvin Van Peebles, all artists remixing older forms with contemporary styles to forge new artistic possibilities. In the case of Scream Blacula Scream, under the surface, this also puts the movie in dialogue with Haitian folklore and its sacred traditions violently brought across the Middle Passage and preserved in the shadows.

It was on Haiti’s sugar plantations where stories of reanimated corpses emerged alongside a New World religious order with zombi revenant eternally trapped in their bodies with no souls. At the turn of the eighteenth century, when slaves fought back against plantation masters and defeated factions of Napoleon’s army, freeing themselves and their country from French colonial rule, the zombi myth was folded into Voudon spiritualism and sailed to the new republic by way of New Orleans. It soon appeared in mutated form in The Black Vampyre, a story of disputed authorship from 1819 set proximate to the Haitian Revolution connecting zombiedom and vampirism, both rooted in historical atrocities.

Again, Scream Blacula Scream’s production fails to sustain this historical dialogue. Yet still, Prince Mamuwalde’s embodiment as the literal curse of colonial displacement is not accidentally profound. Blacula’s reanimation in a Los Angeles neighborhood where charcoaled debris from the 1965 Watts Rebellion would’ve still lined the streets is not a coincidence. This is, unquestionably, serious material, no matter how many rubber bats we see flying on strings. Blacula embodies the long shadow of the plantation and the broken promise of Reconstruction. And a black vampire doomed to seek lifeblood by killing others in his own community—think heroin dealing in Coffy, think the fast-approaching crack epidemic in Compton—is, frankly, more psychologically and socially complex than the central conceit of many, many contemporary Elevateds. The Blacula movies are often more fun, too.

2b

Sticking with the Blacula formula, American International Pictures released a string of black horror films portraying demonic possession, zombies, and vengeful ghosts with Abby (1974), Sugar Hill (1974), and J.D.’s Revenge (1976). Other notable entries include 1977’s horror comedy, Petey Wheatstraw, by director Cliff Roquemore and Rudy Ray Moore, as well as Moore’s own follow-up, Disco Godfather (1979). Given its setting in a gimcrack discotheque, its flurry of karate chops that border on parody, and its occasional PSA overtones, at first glance, Disco Godfather plays like a sendup of 1970s crime cinema at its best and worst. But one of this film’s greatest pleasures resides in its slow-burn mutation from fanciful schlock to full-on horror. Moore’s performance as the “godfather of the disco” is full of heart, motivated by vengeance, yet still steeped in the playful toasting of his most famous X-rated provocateur, Dolemite. The hard-hitting soundtrack by studio legend Ernie Fields Jr. and Juice People Unlimited is no joke (especially its blazing theme song). And the angel dust-fueled psychedelic horror sequences give some of the decade’s more lauded experiments in hallucinogenic filmmaking a run for their money. “Put your weight on it!”

3

Here’s a fun closing thought experiment: At the end of Sinners, in the post-credit sequence, Stack and Mary show up in Chicago in 1992, the same year a Chicago-set horror film about historical trauma, urban decay, and economic dispossession, Candyman, is released. In the world of Sinners, do Stack and Mary go see Candyman at the Oriental Theater inside the Loop, where Blacula premiered? (Perhaps a double-feature with 1992’s Buffy the Vampire Slayer?) Are they fans of Blacula and Scream Blacula Scream? And once Blade arrives?!

Like Blacula’s resurrection from bones and ash, or as the literal translation of “renaissance” should indicate, the current Ascension of so-called elevated horror is exactly that—a rebirth, always.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon