| Ryan Sanderson |

The Quick and the Dead plays at the Trylon Cinema from Sunday, December 14th, through Tuesday, December 16th. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

You’re Sharon Stone. Congratulations. You’ve just achieved massive stardom with Basic Instinct. Now Sony’s come knocking with a metatextual riff on Sergio Leone Westerns, the Clint Eastwood Man With No Name archetype written for a woman. You sign on as both star and producer. No more playing the love interest in some Hollywood leading man’s movie. This is your film, and you get to assemble your team.

You personally request pre-stardom Russell Crowe and Leonardo DiCaprio as supporting actors. The studio doesn’t like either. You’re so certain you wind up paying DiCaprio out of your own pocket. You’re dead right on both counts. Each brings something vulnerable and interesting to their roles.

I especially love your next choice, although I think it will backfire a little in the short term. Sometimes great choices do. You hire Sam Raimi—fresh off capping the Evil Dead trilogy with Army of Darkness. It’s a fascinating choice on every level, and it ensures that, whatever else goes wrong, your film will be very, very watchable.

Raimi admits that he’s a bit out of his depth on this project. “I felt my style didn’t help make it into a great picture. So I kind of stopped making movies for a while and tried to rethink my situation,” he will tell Empire in a 2009 interview. After that rethinking—and a string of great mid-budget “respectable” studio films—he’ll become one of Hollywood’s greatest masters of this exact blend of mainstream camp sincerity. In the early nineties, however, he’s never done any of that. Evil Dead 2 is one of the greatest films ever made, but it works in only one ludicrous register, like if Mozart composed a sonata for the vuvuzela.

Genre revisionism requires a deft touch. The Quick and the Dead, in that context, occasionally feels like someone brought a boomstick to a knife fight.

I can’t believe I’m sitting here arguing that Sam Raimi is what’s wrong with this film. This was not the essay I expected to write at all. Hell, I’m such a Raimi fan that in September I spent over two hundred dollars to see Spider-Man 2 in a near-empty auditorium. There are mitigating circumstances—and it’s the only time in my life I’ve ever done anything like that—but the receipts are still pretty ridiculous:

Special Event Movie Ticket: $11.50

Two More Special Event Movie Tickets for Mom and Sister: $23.00

Three More Special Event Movie Tickets, Ultimately Unclaimed: $34.50

Fandango Convenience Fee: $13.14

Convenience Fee Waiver with Seven Day Free Trial of Fandango FanClub: -$13.14

Forgotten Fandango FanClub Membership for September – $9.99

Forgotten Fandango FanClub Membership for October – $9.99

Forgotten Fandango FanClub Membership for November – $9.99

Forgotten Fandango FanClub Membership for December – $9.99

Bus ticket from Minneapolis, MN to Ames, IA: $57.20

Service fee for bus ticket from Minneapolis, MN to Ames, IA: $3.99

Bus ticket from Ames, Iowa to Minneapolis, MN, 18 hours later: $57.20

Service fee for bus ticket from Ames, IA to Minneapolis, MN: $3.99

Total: $231.34

I did this despite the fact that:

- I’m a 36-year-old man who never feels older than when he watches a new Marvel movie.

- I’ve never spent a fraction of that amount for a single movie in my life before. I think the previous high watermark was the forty bucks I spent for the discontinued Criterion of Akira Kurosawa’s Ran that I found in a Half Price Books more than a decade ago.

- I have seen Spider-Man 2 many, many times in the twenty-one years since it was released. I basically have it memorized.

- I have access to Disney+, the streaming service where I can access Spider-Man 2 whenever I want through any devices they have not figured out are not located in my mom’s house.

- I own Spider-Man 2 on DVD.

- I also own Spider-Man 2 on blu-ray.

- The Fathom Events screening was digital—basically, a glorified blu-ray.

- The film screened was technically not Spider-Man 2. It was Spider-Man 2.1, the vastly inferior special edition full of scenes that were cut from the film for very good reason.

Some explanation: it was my sister’s birthday. It’s kind of our film. The screening seemed too fortuitous to pass up. Plus, just to sit in an auditorium and treat that train scene like an event with someone I love who shares that affection—I would do it again in a heartbeat (although I might check the till a little closer). I’ll always spring for treating cinema like an event when I can, and Sam Raimi in particular makes movies that are very easy to treat that way. Spider-Man 2 is a phenomenal example. Like The Quick and the Dead, it’s a Hollywood genre blockbuster that balances campy action with sincere pathos. It capitalizes on the raw charisma of an acting legend playing the heavy, and alternates between Chaplin-esque physical comedy and surprisingly grounded dramatic highlights like the scene where Peter Parker tells Aunt May what really happened to Uncle Ben. You can see all the lessons of The Quick and the Dead assembled and knocked down like bowling pins.

I guess what I’m saying is, Sharon Stone is a little bit responsible for Spider-Man 2. Which is incredibly nice of her. She’s also very responsible for this immensely watchable, deeply entertaining Western. Only because she took a major risk on an up-and-coming talent, one aspect of the film that gets lost in the shuffle is her performance. And it’s not her fault at all! She’s doing the work. As I said earlier, genre deconstruction requires a deft touch. Not exactly the signature of any eighties trash auteurs, even those like Raimi and Cronenberg who eventually made the transition to studio respectability.

Screenwriter Simon Moore was direct about the fact that his spec script was intended as an homage to Sergio Leone’s Dollars trilogy. Stone’s anonymous demeanor and gruff vocalization are clearly intended to mirror Clint Eastwood’s role in those films. The script uses this comparison in a number of interesting ways. Stone’s Ellen “The Lady” McKenzie is tough and cool, but unlike Eastwood’s 1960s persona, she’s never killed before. Her relationship with killing becomes one of the film’s primary concerns. More interesting is how everyone else treats her. When The Man With No Name walks into a room, everyone makes space for him. When The Lady enters, people either ignore her or try to get in her pants. Her status as a woman in 1800s America is repeatedly brought to the forefront for reasons that have nothing to do with her grit or character. Imagine a scene in The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly where Lee Van Cleef’s Angel Eyes tries to seduce Eastwood’s Blondie the way Gene Hackman’s Herod tries to seduce The Lady. Are you still imagining it? Me too.

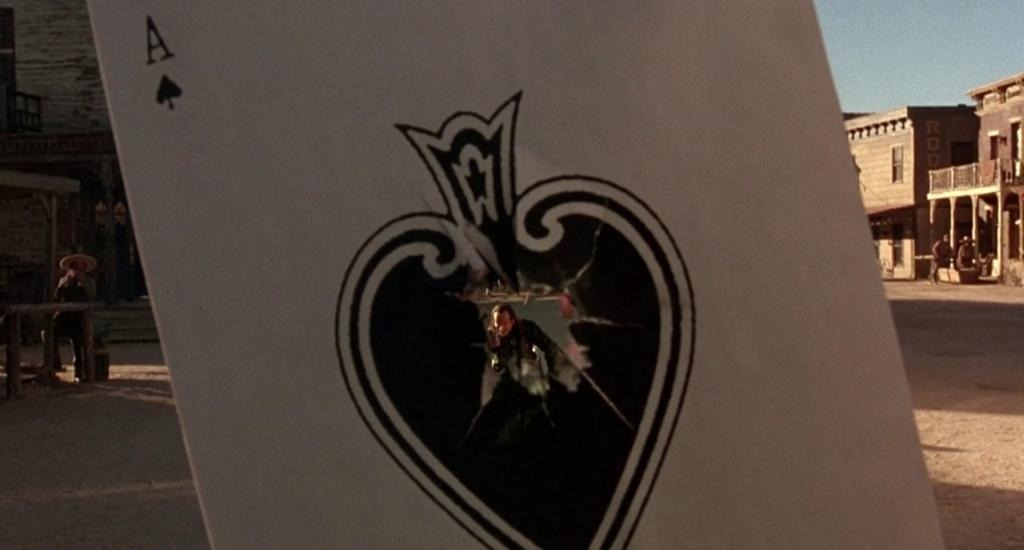

My experience is that these kinds of metatextual comparisons work best when the audience is left to discover them on their own, when the echo or rhyme is layered into a story that works entirely on its own merits. Only Raimi’s direction feels singularly ill-equipped for the precise moments that would bring all of this together. He’s great with the gun-fighting tournament. When I signed up to write about this film, having not seen it in more than a decade, those were the scenes I was thinking about. I expected to show up and write a glowing, borderline obnoxious review about how Raimi’s ecstatic troll of a camera imbues the film’s action with maniacal, unforgettable glee. And it does! The smash cuts and zooms and campy transitions and old-fashioned bigness of it all is really compelling. It renders tiny, unimportant moments compulsively watchable.

And yet, the actual big moments, the ones that are supposed to be showstoppers, fall weirdly flat, and I do think it’s kind of Raimi’s fault. I’m not alone in this observation. In that same Empire interview, Raimi said, “I had a tremendous amount to learn about directing actors. And that style is only so satisfying.” His previous experience was seeing how many things he could get Bruce Campbell to smash over his own head (again, brilliantly). And somewhat to his credit, everyone on screen is doing a fantastic job. Crowe’s Cort carries a wounded, almost pathetic energy through his scenes, running perfectly counter to his status as the primary heroic male. DiCaprio’s The Kid wears his blatant insecurity a millimeter beneath his mask of arrogance. The bit players likewise do the best they can with their roundtable of archetypes. Keith David’s Sergeant Clay Cantrell is phenomenal, a natural consequence of being played by Keith David. I also love Lance Henriksen’s Ace Hanlon. Except when an actor’s really delivering the goods, when all you need to do is linger on the face muscles, The Quick and the Dead suffers from a twitchy trigger finger. It’s always searching for the most obvious visual metaphor, the most blatant camera movement, the most hyperbolic framing to wrap around every emotional moment, smothering genuine pathos in a sea of affectations.

The one exception is Gene Hackman. God, he’s incredible in this. It’s like nobody told him Unforgiven had stopped shooting. I don’t know if Raimi just had more reverence for the living legend or if there was just no way to shoot around a face that expressively menacing, but either way—and I know this is heretical—I think it’s one of the best performances of his career. He’s so monumentally detestable in ways that still feel anchored in genuine humanity. I lay awake at night wondering what someone would have to do to themselves inside to embody that much convincing ugliness. So thank you Sharon Stone, for your many contributions to this glorious, flawed oddball of a Western. I’m sorry I didn’t work out as well for you, personally (the film was a modest commercial and critical flop on release, making back roughly half of its budget domestically, coming in second on opening weekend to Billy Madison). On the bright side, you kickstarted a number of careers that delivered dozens of the best movies ever made (and a number of my personal favorites). And you got a cool (and well-deserved) series at my favorite theater in the Twin Cities. I think a large number of cinephiles wonder what they would do if they got the chance to headline and assemble their own major studio film. I can’t imagine anyone doing it better.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon