|John Moret|

In the spring of 1970 a charismatic bit player and stuntman named Bruce Lee approached Warner Brothers to produce a show about a Shaolin Monk in the American West. Warner Brothers gave the greenlight for the show and cast a white actor in the role of the monk, leaving Lee furious. A frustrated Lee left the United States for Hong Kong, where he starred in hit after hit. In the States, the films Lee made in Hong Kong were released with confusing and mixed-up titles, especially following the success of Enter the Dragon. When Big Boss was released, it was under the titleFist of Furyˆ––and Fist of Fury was released as The Chinese Connection. These US releases were strangely dubbed versions that retained Lee’s signature attack yells and nothing else—but that was enough for 15-year-olds in small, southern Minnesota towns to fall in love with the sound of that yelp on VHS tapes decades later. The voice actors seemed to play every character, except Lee himself, as comedic relief. None of this got in the way of my sheer delight in watching them. In fact, though I recognize that the films can be taken seriously in an entirely different manner when not dubbed, I still have a nostalgic fondness for those versions.

Watching the newly restored versions of these films has been a fascinating re-education for me.The Big Boss, for instance, was seen by my 15-year-old self as simply a great action picture, which it is. Seeing it this time around, there are so many elements that I didn’t notice before. For one thing, the film is a biting critique of capitalism and union busting. When a few of the workers go missing for asking questions about what’s being distributed inside of the ice they are manufacturing, “the big boss” sends a busload of thugs to put down the striking workers. Likewise, when the workers win with the help of Cheng (Lee), the big boss makes Cheng the new foreman, undermining the resentment of the workers for a time. Recognizing these anti-labor tactics adds a completely new dimension, especially because it was meant to attract audiences in communist China.

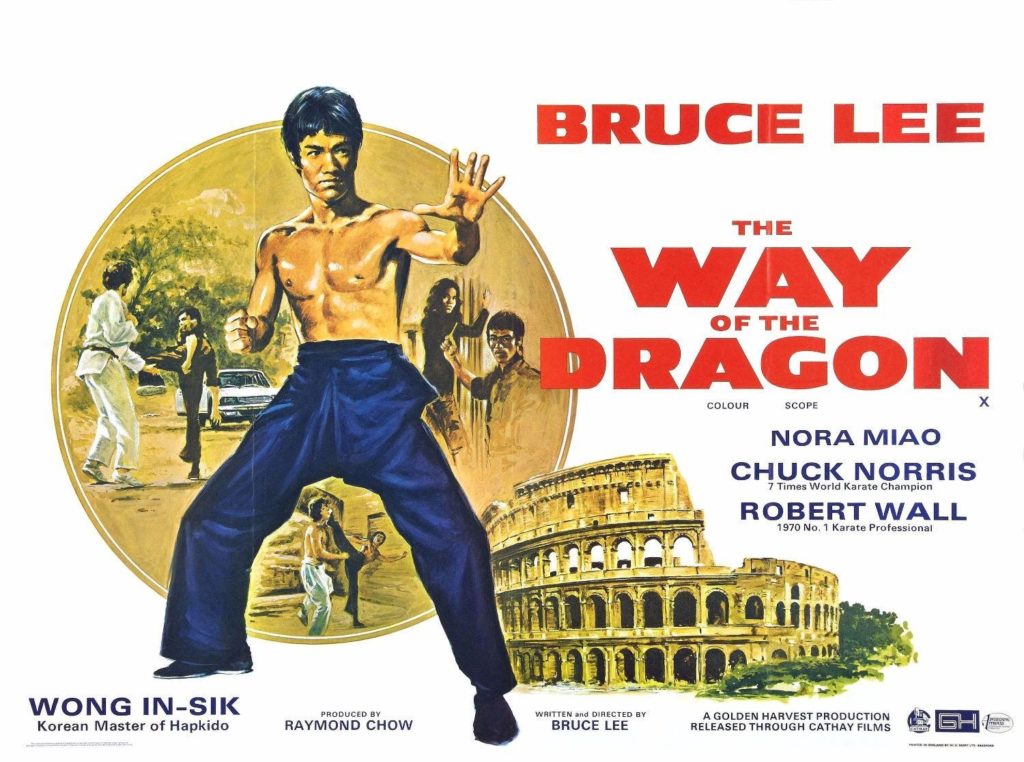

The other thing that sticks out to me is the representations of race and culture. In Fist of Fury the villains are made up of the occupying Japanese forces. As an aside, the Japanese make up a large percentage of the villains in Chinese kung fu films. Likewise, in The Way of the Dragon THE WAY OF THE DRAGON the villains are Italian mobsters and American mercenaries; the villains tweaked to speak to respective audiences. Here too, thinking about the audiences in China during the Cold War places these films in a place diametrically opposed to my 15-year-old self-identity. Yet, the richness of Lee’s complicated relationship with the United States plays into all of this.

The Hong Kong films that Bruce Lee worked on completely transformed the action genre across the globe. Studios like Shaw Brothers and Golden Harvest had been producing these kinds of films for a while and they were extremely successful in Asian markets. In the midst of the Vietnam War, US distributors were wary of making an action film with an Asian star. However, on the heels of these Hong Kong breakout films, Warner Brothers sought to try out a different kind of film with Lee in the central role. Lee understood they needed to capture multiple audiences to make the film a success—John Saxon to attract white audiences,featured heavily in all the marketing, and the star of Black Belt Jones, Jim Kelly, to attract black audiences. And so, with success in mind above principals, Lee convinced WB to unwittingly make the first cross-cultural phenomenon film by putting together a global inter-racial partnership the likes of which we see replayed in every Fast and the Furious film since.

Enter the Dragon’s production was aghast with problems. Aging equipment, which the US crews had trouble operating (but the Shaw Brothers and Golden Harvest crews had no problem using) meant that all of the film’s dialogue was captured later, in the same manner as a Spaghetti Western. Multiple fights broke out among extras and Lee was attacked by an extra attempting to prove his mettle. Lee dispensed of the attacker easily and sent him back to work. Lee was hurt multiple times by some of the 8,000 shattered mirrors and broken bottles (they used REAL bottles!?). And yet, Lee was the force behind the film that kept it moving. And, because of that these films have a loyal following in the States that has endured for 50 years.

In short, these films, like so many of the great Kung Fu films of its time, were dangerous. And, you can feel it when you watch them. The fight scenes are raw and wide-angled without the digital masking of computer graphics. Lee’s performances carry a weight and sincerity that would forever make him revered. One of my favorite examples is his nonchalance when entering into the big fight scenes––especially in The Big Boss when he is snacking on something from a white bag while walking towards some henchmen with knives.

Sadly, Lee died a month before the release of Enter the Dragon, so he never got to see what it would become. Luckily, we did. And, luckily, we finally have new restorations of his Hong Kong films.

The international distribution of Lee’s Hong Kong films have been difficult for years. When I originally tried to book this series seven years ago, I hit roadblock after roadblock. There were no good screening materials. I was only able to track down a handful of 35mm prints in the hands of private collectors in the States and I was told they were in rough shape. There were no restorations available either. Likewise, the distributor, Fortune Star, had little interest in booking these films here so the prices were enormous. In 2016 Fortune Star began their restorations of these four films from the original 35mm negatives in both Hong Kong and at L’immagine Ritrovata in Bologna, Italy. Janus Films has released these films here in the US. Who knows how long we’ll have them?

Edited by Michelle Baroody

“The Way of the Dragon: The Hong Kong Films of Bruce Lee” runs throughout February a the Trylon and begins screening at the Trylon on Friday, February 5. For more information, visit trylon.org. We’re still operating at a limited capacity, so please book your ticket in advance and don’t forget your mask!