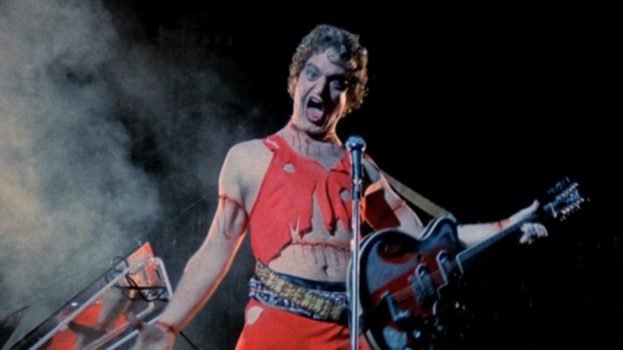

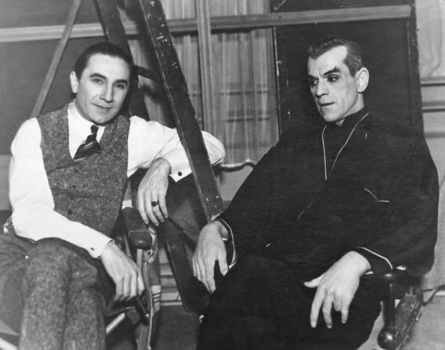

“A Masterpiece of Murder”: Universal’s All-Star Monster Mash The Black Cat

|Alex Kies| In 1934, Universal Studios was a house divided. Despite the protestations of studio head “Uncle” Carl Laemmle, his nephew, 23-year-old Carl “Junior” Laemmle, one of Hollywood’s foundational nepotism hires, had inaugurated the golden age of studio horror… Continue reading