|Alex Kies|

Catch The Black Cat at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, October 23 to Sunday, October 25. And don’t miss other Karloff films in the series Boris Karloff’s Mad Genius. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

Economic constraints undoubtedly gave rise to flashes of inspiration and images dreamed up with a view to economy could have universal repercussions… We can often see the B movie as an active center of experimentation and creation.

– Gilles Deleuze[1]

In 1934, Universal Studios was a house divided. Despite the protestations of studio head “Uncle” Carl Laemmle, his nephew, 23-year-old Carl “Junior” Laemmle, one of Hollywood’s foundational nepotism hires, had inaugurated the golden age of studio horror with Tod Browning’s Dracula and James Whale’s Frankenstein in 1931. Although Uncle Carl was not fond of the horror genre, there was no denying their success. Dracula was Universal’s biggest hit of 1931, bringing in a profit of $700,000, which prompted the production of Frankenstein, which Universal reported made $708,000 in profit.[2]

In Dracula, Bela Lugosi had given an iconic performance as the titular count in his fourth language, English. Uncle Carl Laemmle had been keen to create a new Lon Chaney, a man of a thousand faces, and thought Lugosi might fit the bill. After his memorable but performance under heavy makeup in The Island of Lost Souls (1932), Lugosi had been cast as the Creature in an aborted Universal production of Frankenstein, which would have been directed by the versatile and innovative Robert Florey, with whom Lugosi instead made Murders in the Rue Morgue (1932). Florey did complete a screen test for Frankenstein with one shot of Lugosi as the monster. No photos were taken, and the footage was lost.[3]

James Whale, a respected filmmaker in his native England, had just arrived in Hollywood and was a hotter ticket than Florey. Whale expressed interest in adapting Shelley’s novel and was given the assignment. He cast his countryman Boris Karloff as the creature, whom he’d already directed as a lumbering semi-mute man-monster to great effect in The Old Dark House (1932).

Lugosi did not give up the role without a fight. He lobbied the Laemmles hard, but Whale had made up his mind and had considerably more influence.[4] Lugosi soldiered on, giving a great turn in Murders of the Rue Morgue, but his subsequent roles over the next few years were smaller and less prestigious, sometimes even uncredited. He was frustrated with being typecast as a villain and returned to the stage in search of better parts, to mixed results. In 1934, he was touring vaudeville in an 18-minute dramatization of Dracula to recover from a bout of financial insolvency.[5]

Meanwhile, Karloff had capitalized on his Frankenstein caché with juicier, more prestigious parts in more respectable non-genre films. He was second billed in John Ford’s The Lost Patrol as a crazed religious fanatic, and as the anti-Semitic villain Count Ledrantz in the Oscar-nominated social commentary picture The House of Rothschild, playing against type and directed by his idol, George Arliss, the first multi-hyphenate theater practitioner to mount a wildly successful biography of Alexander Hamilton. The House of Rothschild is now infamous for being included in the Nazi propaganda film Der ewige Jude (1940) as an example of Jewish propaganda, despite being produced entirely by well-meaning Gentiles.

While these films were good for Karloff, they were both produced by MGM, which took out Karloff’s contract on loan from Universal. Therefore, the Laemmles wanted to reassert Universal’s association with Karloff, even if that meant another horror picture. Junior commissioned several adaptations of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Black Cat” as a Karloff vehicle but was unsatisfied with each attempt.

Meanwhile, Junior had become fast friends and confidants with a mysterious young immigrant filmmaker, Edgar Gerome Ulmer. Then and now, Ulmer’s background has been the subject of quite a bit of mythmaking. In a series of interviews with Peter Bogdanovich in the early 1970s, months before his passing, Ulmer made some grandiose albeit nearly unverifiable claims about his life.

Over the years, Ulmer provided several different birthdates and places. Historian Bernd Herzogenrath has determined Ulmer was born in 1904 in Olomouc, Moravia, a state of the Austro-Hungarian empire now recognized as Czechia. We know Ulmer as a young man was heavily involved in the German stage and screen at the height of expressionism. He co-directed the 1930 city symphony People On Sunday, a who’s who of international film history: Ulmer’s codirector was Robert Siodmak (The Killers [1946]), Siodmak and Ulmer cowrote the script with Billy Wilder (Some Like It Hot [1959]), and Fred Zinnemann (High Noon [1952]) assisted cinematographer Eugen Schüfftan, who, beyond inventing the Schüfftan Process (a precursor to green screen techniques), shot Georges Franju’s Eyes Without a Face (1950), one of the most beautiful horror films ever.

As for Ulmer’s resumé, he claimed to have been a key design collaborator with F.W. Murnau on Sunrise, Faust, and Tabu. He claimed to have designed the iconic sets in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920, when Ulmer was 16). He even claimed to have ghost-directed not only for Murnau, but also for Erich von Stroheim, William Wyler, and Fritz Lang. In fact, he claimed to have invented “production design” and even the moving camera itself.

Ulmer had an extended relationship with both Laemmles. Uncle Carl was constantly scouring Europe for talent. There is photographic evidence of Ulmer on the Universal lot in the late 1920s, and Ulmer wrote several letters home during that time. He later told Bogdanovich he’d accompanied Murnau to Hollywood, and Uncle Carl had been impressed enough to periodically take a loan out on Ulmer’s German contract. None of the resulting work is credited, however, and we have only Ulmer’s word to go on. Between being a favorite employee of Uncle Carl’s and friends with Junior, it wasn’t long before he was offered the reigns of The Black Cat.

Ulmer had moved permanently to America in 1932 and his first North American solo directing credit was Damaged Lives, a syphilis drama produced by the Canadian Social Health Council. While the subject matter and the fleeting full-frontal female nudity ran afoul of state censorship boards, it was a big hit. Based on box office receipts, historian Eric Schaefer estimates that 60% of adults in Baltimore saw Damaged Lives in theaters.[6]

Although today we remember The Black Cat primarily as the inaugural screen pairing of Karloff and Lugosi, as production began, Universal’s publicity department advertised Edgar Allan Poe equally with the leading men. In fact, a lobby card referred to the combination of Dracula, Frankenstein, and Poe as “tremonstrous.”[7]

Poe enthusiasts would be disappointed, however. In fact, in 1965, Karloff said of the adaptation: “Poor Poe. The things we did to him when he wasn’t there to defend himself!”[8] Only two thematic aspects of Poe’s story survived the original draft Ulmer wrote (with dialogue by crime novelist George Sims, writing as Peter Ruric): revenge and eerie recurring appearances of a black cat. If the script has any basis in Poe at all, there are a couple whiffs of “The Cask of Amontillado.” Everything else in the script had more topical, macabre inspirations.

The primary influence on The Black Cat was a story then leading the British tabloids. Nina Hammett, the self-appointed “Queen of Bohemia” and model for Henri Gaudier-Brzeska’s Torsos, had released her memoirs, Laughing Torso, in the UK. In it, she alleged that while visiting Sicily contemporaneous with Aleister Crowley’s residency (he was later exiled by the Fascists), an infant had mysteriously disappeared and a goat in town had been found mutilated. She mentioned these rumors in conjunction with locals’ fears of Crowley’s purported black masses. Crowley, having by then exhausted his considerable inheritance, sued for defamation. The tabloids, along with Ulmer and Ruric, ran with it.[9]

It is often said The Black Cat is one of the great Pre-Code horror films, which is true although a bit misleading. The original Production Code had been written in 1930, and Joseph Breen founded the Production Code Administration soon thereafter. Although studios submitted their scripts to the PCA for guidance, the Administration’s rulings were not considered binding until July 1, 1934, six weeks after The Black Cat was released theatrically. [10]

After meeting with Ulmer and Ruric, Breen issued a 19-point memo to Universal about the script’s unacceptable themes and content. Invocations of Satanism, cannibalism, necrophilia —not to mention dialogue ascribing these traits specifically to Hungarians—and graphic violence against humans and animals alike were not going to fly.

The Depression was in full swing, and the film industry was not immune to the national shortage of disposable income. Controversial films, especially horror and gangster pictures, attracted theatergoers but also moralistic ire. The Catholic Church spearheaded boycotts of not just movies that fell short of their definition of decency, but all movies. Formal censorship fell to the discretion of individual states’ dedicated boards, but there were rumblings of censorship coming on a federal level. The foundation of the Production Code Administration and the subsequent expansion of its authority had been efforts to preempt boycotts and external censorship through self-policing.

Ulmer and Ruric retooled the script but went into production without getting a final “OK” from any Universal executive. The Laemmles were in New York meeting with investors, and Uncle Carl had gone from there to Carlsbad for vacation. Universal allotted $91,000 (just over $2 million now) and 13 days to shoot The Black Cat. For comparison, Dracula had been budgeted $355,050 over a 36-day shoot. Frankenstein had gone over time and budget, taking six weeks and costing $290,000.[11]

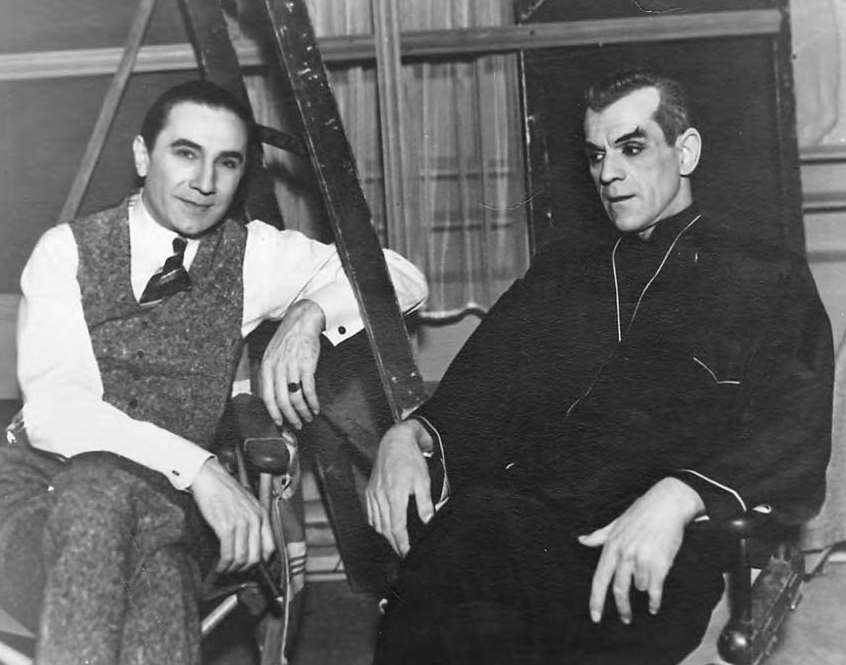

As extensively documented by historian Arthur Lennig in his Lugosi bio-cum-hagiography The Immortal Count: The Life and Films of Bela Lugosi, Karloff was paid $7,500 for The Black Cat whereas Lugosi commanded $3,000.[12] No official reason for this discrepancy was given, nor since discovered.

Starting with the announcement of the casting, public speculation about a rivalry between the two abounded. Part of this was public relations. Columnist Jimmy Starr of The Los Angeles Evening Herald Express commented: “Can you imagine Dracula trying to outscare Frankenstein? Or vice versa? That will be just DUCKY!”[13] Later, Starr wrote of the production:

They are ACTUALLY trying to out-scare each other and have resorted to the ancient Hollywood trick of attempting to steal scenes, resulting in a sneering contest when the cameras aren’t in motion. Boris is said to have sneaked in on some of Bela’s publicity photographs. And the feud is on—and in earnest![14]

Any real rivalry, of course, may have been partly due to the pay discrepancy or Karloff’s procurement of the Frankenstein role, which Lugosi did eventually portray in Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man (1943) (written by Curt Siodmak, younger brother of former Ulmer collaborator Robert). No primary sources from the set indicate any friction between the two, and both spoke highly of one another later in life and in the press (contra Tim Burton’s Ed Wood [1995]).

Script supervisor Shirley Kassel and actress Lucille Lund both indicated in later interviews that Karloff was more popular on set than Lugosi. This could be attributed to Lugosi’s inexpert English. Karloff himself opined later that Lugosi was wary of being taken advantage of:

He made a fatal mistake. He never took the trouble to learn our language. Consequently, he was very suspicious on the set, suspicious of tricks, fearful of what he regarded as scene-stealing. Later, when he realized I didn’t go in for such nonsense, we became friends.[15]

Edgar G. Ulmer had no such difficulty making friends. Before shooting began, Junior Laemmle fatefully introduced Ulmer to his cousin, Max Alexander, and even more fatefully to Alexander’s wife and The Black Cat “script girl,” Shirley Kassel. Alexander and Kassel had been married just under a year, and the union would not last into 1935.

It would be prudent at this point to establish the plot of The Black Cat in order to discuss its production in more depth. Outside Omsk, Peter and Joan Alison (David Manners and Julie Bishop), a young American couple honeymooning on the Orient Express, meet Dr. Vitus Werdegast (Lugosi), “the most respected psychiatrist in Europe,” who informs them he is returning to the area for the first time in 15 years.

After a bus accident, Joan is injured and rendered unconscious, and Werdegast brings the Alisons to what just happens to be his intended destination: an art deco mansion designed by and belonging to architect Hjalmar Poelzig (Karloff). Poelzig has perversely constructed his mansion on the remains of Ft. Mamaros, the site of a battle that ended with Poelzig betraying his comrades—Werdegast included—to the advancing Russians. This resulted in Werdegast being imprisoned and Poelzig stealing the former’s wife and child.

Poelzig indeed married Werdegast’s wife, but when she died from unspecified causes, he preserved her in a glass coffin in his expansive basement and married Werdegast’s daughter. Furthermore, Poelzig, a practicing Satanist, intends to sacrifice Mrs. Alison (implied, thanks to the PCA, to still be a virgin), who bears a striking resemblance to both Werdegast’s ex-wife and daughter, in a black mass. The titular cat periodically menaces Werdegast, who is deeply ailurophobic, and he kills it each time.

That’s a lot of plot for a 63-minute movie, and as you might imagine, it doesn’t quite cohere. For example, it is not explained how exactly Dr. Werdegast practiced psychiatry to such acclaim while imprisoned in Kurgaal. These plot holes may be explained by a week of extensive re-shoots mandated by the studio on behalf of the PCA.

The most significant alteration was softening the Werdegast character. In the original script, when Werdegast and Poelzig discuss the latter’s plans for the Alisons, it’s over a game of chess as in the final version, but instead of playing for the Alisons’ safety, they play for the rights to Mrs. Alison.[16] This is perhaps why one press booklet referred to The Black Cat as a battle between “two arch-fiends!”[17]

Oddly, the result is one of Lugosi’s few non-villainous screen roles, which he’d coveted after Dracula. During a 1955 repertory screening of The Black Cat, Lugosi reportedly remarked at his introductory soft-focus close-up, “What a handsome bastard I was!”[18]

Ulmer, however, did try to stick it to the Production Code Authority. The PCA requested the removal of all shots of the mummified Mrs. Poelzig (née Werdegast) in her eerie glass coffin. Ulmer replaced those with new shots where she is only one of many of women preserved in Peolzig’s infernal basement. Somehow, these shots remain in the final version.[19]

The main set of the film, Poelzig’s mansion on the ruins of Fort Mamaros, is a wonder of production design and was all Ulmer’s handiwork. The exterior process shots of the hilltop mansion overlooking an unkempt battlefield graveyard are based on Frank Lloyd Wright’s Ennis-Brown house, so much so that some Hollywood tours referred to it as “The Black Cat house.”[20]

The interior sets are all strong lines, long shadows, and glass bricks, the very apogee of filmed art deco. The gruesome basement, the Satanic altar, and the “embalming rack” are vast black voids through which their anxious inhabitants scurry. When Peter Bogdanovich interviewed Ulmer for his book King of the B’s, he asked about the set design. Ulmer said, “It was very much of my Bauhaus period.” We will never know the extent of Ulmer’s scenic work on various masterpieces of German expressionism. However, Poelzig’s mansion set remains on par with any in those films.

The magnificent sets and what one reviewer called the “improper faces”[21] of the leads are enhanced by gorgeous chiaroscuro photography by returning Ulmer collaborator Eugen Schüfftan.

Ulmer was a music fanatic, and unlike the eerie silence of Browning’s Dracula, The Black Cat is suffused with music. The Alisons’ love theme is a straight lift of Tchaikovsky’s Romeo and Juliet. Four or five different Liszt pieces, notably the “Rakoczy March,” are used. Bach, Beethoven, Brahms, Schubert, and Schumann are also featured. Carl Laemmle Senior was furious about this, insisting the American public did not go to movies to hear classical music.[22] He was thankfully overruled.

Whereas James Whale’s Frankenstein and Bride of Frankenstein are very English interpretations of English source material, and Kentuckian Tod Browning’s European settings in Dracula are unspecific, The Black Cat is unmistakably immersed in Teutonic culture and history. Besides the Bauhaus sets and the heavy reliance on Germanic composers, the inciting incident of the plot is World War I. This Werdegast monologue indicting Poelzig is far more attuned to real-life horror than other Universal pictures:

You sold Mamaros to the Russians. You scurried away in the night and left us to die. Is it to be wondered that you should choose this place to build your house? A masterpiece of construction built upon the ruins of the masterpiece of destruction—a masterpiece of murder. The murderer of 10,000 men returns to the place of his crime. Those who died were fortunate. I was taken prisoner at Kurgaal. Kurgaal, where the soul is killed, slowly.

While shooting the scene in which Werdegast is about to flay Poelzig alive, Lugosi became very emotional and struggled mightily with his lines.[23] Ulmer in hindsight chalked it up to Lugosi’s limited English. However, it is worth considering that Lugosi and Werdegast are both Hungarian exiles, veterans, widowers, and, at least according to his final wife Hope Lugosi, resentful of Boris Karloff and deeply afraid of cats.[24]

This is what makes The Black Cat one of the singular examples of the first cycle of Universal horror films. Unlike Dracula, Frankenstein, or The Phantom of the Opera, which all feature monsters, The Black Cat is a horror film that focuses on man’s inhumanity to man. There were never Poelzig action figures or Werdegast postage stamps. The horror is man’s inhumanity to man.

James Whale of course was no slouch, and neither was Tod Browning, but their cameras look creaky compared to the dynamic direction in The Black Cat. The finales of both seem stagebound compared to an almost unprecedented 116 shots in the seventh reel of The Black Cat.[25]

Thirty years after the film, the Cahiers du Cinema critics (in particular Truffaut, Moullet, and Tavernier) raved about these shots, especially one where Karloff opens a door for a suddenly non-diegetic camera, which wanders the darkened Haus Poelzig while the sinister architect discusses post-war morality over the furtive strains of Beethoven’s Seventh. In fact, there’s so much to look at I only noticed cameos from Andy Devine and John Carradine (who later saved one of Ulmer’s children from drowning)[26] after I’d read they were in it and rewatched the film, looking for them. Ulmer biographer Noah Isenberg stresses the direction of The Black Cat isn’t inspired by German Expressionism, it is German Expressionism, and might take some American audiences in 1934 (even horror fans) aback.

Shortly after post-production wrapped, Ulmer and Kassel eloped after falling in love on set. Junior’s friendship could not save Ulmer from the consequences of stealing the boss’ nephew’s wife, and he was informally blacklisted. Ulmer and Kassel remained married until he passed in 1971, and she was script coordinator on every film he made from The Black Cat onward.

Despite the troubled production, unfavorable reviews, and inevitable religious backlash, the powerful visuals and the onscreen sparks between Karloff and Lugosi made The Black Cat Universal’s biggest financial success of 1934 (the low budget didn’t hurt), turning a profit of over $155,000. They went on to co-star in six more Universal films (another of which was also called The Black Cat).

Karloff worked steadily for the rest of his life, enjoying relative esteem, whereas Lugosi was soon confined to Poverty Row and struggled with bankruptcy. Compare their final films. Karloff collaborated with Ulmer fan Bogdanovich on the meta-thriller Targets (1968), whereas Lugosi passed during production on Plan 9 From Outer Space (1959).

Ulmer likewise spent the rest of his career on Poverty Row. He made Detour, Bluebeard (starring John Carradine), and The Man From Planet X, easily some of the best Poverty Row films not directed by Orson Welles. Although the minimalist spaceship sets of The Man From Planet X are impressive feats of atmosphere, there’s no comparison to Poelzig’s mansion.

Ulmer did enjoy some recognition in the last years of his life, receiving two major write-ups during the peak of Cahiers du Cinema, and he was the subject of appreciations by influential filmmakers like Bogdanovich. In his book The Films of My Life, François Truffaut said Ulmer’s late period western The Naked Dawn showed him how to make Jules and Jim, and that one could tell it was the work of a good man.[27]

The Black Cat would be the only film Ulmer made with studio time and resources. Ithad a lower budget and shorter schedule than most Universal horror films, but Ulmer only ever had a fraction of that money and a maximum of five shooting days for the rest of his career. Regardless of these intrigues and what-ifs, The Black Cat endures as a superlative example of Pre-Code genre cinema, the best Karloff-Lugosi film, and a testament to Ulmer’s mastery of the form.

NOTES

[1] Deleuze, Gilles, Cinéma 1—The Movement Image, trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Barbara Habberjam, (Minneapolis: The University of Minnesota Press, 1986), 162-163.

[2] Jacobs, Stephen, Boris Karloff: More Than a Monster, Sheffield, England: Tomahawk Press, 2011), 107.

[3] Lennig, Arthur, The Immortal Count: The Life and Films of Bela Lugosi (Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky), 141-147.

[4] Lennig, 143.

[5] Lennig, 195.

[6] Schaefer, Eric (1999). “Bold! Daring! Shocking! True!”: A History of Exploitation Films, 1919–1959. Duke University Press. 180, 419.

[7] Lennig, pp. 209.

[8] As quoted in Mank, Gregory W., “Improper Faces—The Black Cat,” in Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff: The Expanded Story of a Haunting Collaboration, with a Complete Filmography of Their Films Together, Revised and Expanded (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2009), p.153

[9] Lennig, 197.

[10] Black, Gregory D., Hollywood Censored: Morality Codes, Catholics, and the Movies (Cambridge University Press, 1996), 91.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] As quoted in Mank, 161.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid, pp. 180.

[16] Lennig, 202.

[17] Mank, pp. 153

[18] Gregory W. Mank, “The Last Bride of Dracula,” Cult Movies, p. 46.

[19] Gregory W. Mank, Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff, p. 192.

[20] Mank, Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff, pp. 168

[21] Ibid, 198.

[22] Ibid, 193.

[23] Lennig, p 206.

[24] Mank, Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff, p. 191.

[25] Lennig, 205

[26] Mank, Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff, p. 185.

[27] Truffaut, Francois, “Edgar G. Ulmer: The Naked Dawn,” in The Films of My Life, trans. Leonard Mayhew, (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1985), 155-156.

Edited by Matt Levine