| Terry Serres |

The series Agnès Varda: Dieu de Cinema screens every Sunday to Tuesday in May at the Trylon Cinema. For tickets and more information visit trylon.org.

Agnès Varda is variously termed the godmother, the grandmother, or the mother of the French New Wave (in ascending order of Google hits). While it is certainly high praise to be accorded primacy in such an important movement of filmmaking, these phrases imply more of a catalyzing or even ancillary role than one of full belonging. Alexandra Schwartz in The New Yorker puts the right spin on Varda’s relationship to the movement’s camera- and pen-wielding firebrands: “The truth is that, in more than sixty years of filmmaking, she charted a course unlike any other. Her wave was her own.”[1]

Whether we think of her as off on her own path or as part of the gang, it’s indisputable that Varda was as pioneering and revolutionary and independent as any of her confrères. Her first film, La Pointe-Courte, predates by three years Claude Chabrol’s Le Beau Serge, which is the canonical opening salvo (if debatably so) of the French New Wave.[2] Shot for $14,000 with no studio connections, La Pointe-Courte introduces most of the New Wave hallmarks: neorealism, documentary footage, a cast of professionals and non-professionals, shooting on location (with writing credits to local collaborators), long takes, parallel narratives, fractured idealism, ambiguous ending.[3] The New Wave’s trademark jump cuts figure not so much here, but Varda does amazing things with light, perspective, framing, and juxtaposition. Alain Resnais edited the film, getting paid in lunches. Even though La Pointe-Courte never got an official theatrical release, it didn’t exactly fly under the radar. It screened at the arthouse temple Studio-Parnasse on the Left Bank[4], sharing a double bill with Jean Vigo’s documentary short À propos de Nice. Budding film nerd François Truffaut, 23 years old at the time to Varda’s 27, was perplexed by La Pointe‑Courte and on the fence about its merits, but interested enough to encourage his film bros to check it out. His mentor André Bazin was nonetheless a fan. Part of Truffaut’s problem is that he had no way to contextualize Varda’s accomplishment intellectually, that’s how out-of-the-blue she was.[5]

Trained in photography, Varda first traveled to the port of Sète to snap pictures for a friend who was unable to visit her home town. The port’s fishing quarter, la Pointe Courte, so intrigued Varda that she conceived a story to tell and rented a motion picture camera. She had no filmmaking and scant prior filmgoing experience. The result was vastly more accomplished than merely extending still photography across the dimension of time. (There is an example of photo-montage in Varda’s filmography, the 1963 short Salut les Cubains made soon after the Cuban Revolution, and it’s still pretty terrific. Especially inventive are the passages where image sequences keep time with the music.)

Despite the success of La Pointe-Courte, Varda spent another seven years raising the money for Cléo from 5 to 7. In the meantime she kept her career afloat with commissions from the French Tourism Office: Ô saisons, ô châteaux (O Seasons, O Castles) and Du côté de la côte (Along the Coast), both available on the Criterion Channel in glorious restorations. If Varda had done nothing else but short-form travelogues, she would have had a notable career. You see her talent and themes flourishing already: her knack for free association and word play, her deftness at stitching together cinematic collages from disparate elements, her eye and ear for local color, her fondness for the French countryside and lifelong love of the ocean.

Varda’s journey to becoming my favorite filmmaker was slow and patient. I watched The Gleaners and I with a cinephile friend at the Angelika during a visit to New York City in 2000. It instantly became my favorite documentary, outranking Errol Morris’s microcosmic Fast, Cheap & Out of Control (1997). Oddly, this appreciation provoked no curiosity about the director’s earlier work. I just wasn’t in an auteur headspace. Aside from Woody Allen (whose Annie Hall was for decades my favorite film), Almodóvar (the queer cinema of my youth), and Rohmer (“Cool! Movies about conversations to inspire conversations about movies!”), I seldom sought out movies based on the director’s reputation.

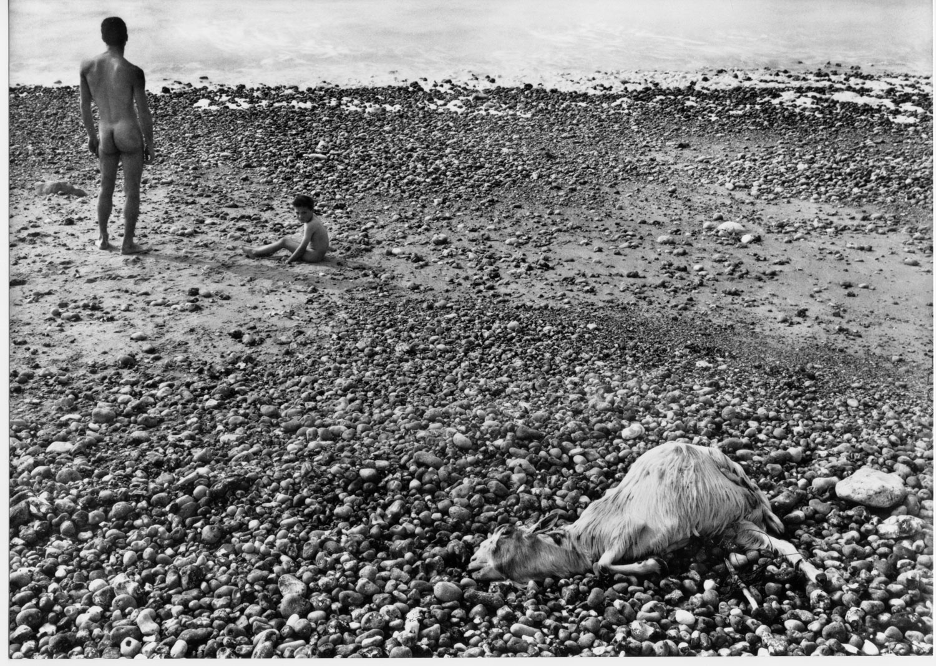

So, I didn’t encounter Varda again until a 2013 trip to Sweden. The Bildmuseet Umeå was showing a retrospective of her multimedia art installations that occupied four of the museum’s six floors. It included enlarged stills from Black Panthers (her 1968 short about the activist organization), unusual triptychs where a central photograph was flanked by looped motion images, her famous seashore nude Ulysse, and the fascinating audiovisual installation Some Widows of Noirmoutier.

Image: https://ps21chatham.org/event/agnes-varda-festival-daguerreotypes-and-ulysse/ulysse-varda/

The Widows installation was a collective portrait of the grief shared by bereaved women in a coastal community whose men had been mostly sailors and fishermen. A large central screen shows women dressed in black, circling a table standing starkly on the beach. Around this screen are positioned fourteen monitors, each with a looped film where one widow tells her story. The gallery’s viewing space has fourteen chairs and pairs of headphones, for each monitor. Visitors move from chair to chair, from widow to widow, from story to story. The footage, arranged sequentially, can now be watched as a conventional documentary on the Criterion Channel. I recall being struck once again by Varda’s deep humanity. But also by how a filmmaker well into her 80s was still experimenting with form and narrative in probing multimedia works.

As absorbing as this exhibition was, another five years passed before I thought to watch the famous Cléo from 5 to 7, which I’m quite sure I had always conflated with Rohmer’s Chloe in the Afternoon. That was in January of 2019, and I was prompted to an immediate rewatch to imprint the magic. At last the spell was cast. I was enchanted by the film’s restraint and economy, by the surface charm and troubling undertow, by the verbal/visual play on the idea of reflection, and by the interiority of Corinne Marchand’s performance. Cléo immediately supplanted Annie Hall as my all-time favorite film. I experienced the epiphany: Agnès Varda—Dieu du Cinéma, to borrow a phrase.

Two months after my Cléo moment, the Dieu du Cinéma had returned to heaven, and I began in earnest an in-depth exploration of her filmography. Each film was a deep dive: watching with English subtitles, then with French subtitles, then without subtitles. If the screenplay was available, I’d read that. When I had the bandwidth, I’d seek out contemporary reviews or read scholarship. Mostly I journaled, penning discursive reviews on Letterboxd––musing and meandering and marveling. A year later, Covid‑19 hit and I expanded my studies to include four more Francophone directors: Chantal Akerman, Claire Denis, Céline Sciamma, and Mati Diop. I didn’t merely want to watch great cinema. I wanted to probe creative genius through the evolution of a body of work, the trajectory of a career, the feedback between success and failure, the catalysts and constraints of creativity. Currently, I am eighty percent through the five filmographies and it’s the journey of a lifetime. Along the way, I have enjoyed the company of two “film fatales” from the coasts, Michalle and Julia. Under the rubric of Club Varda–Akerman–Denis, we connect through watch parties and never-ending chat threads. These intrepid cinephiles call out my sexism, expose my blinders and blunders and biases, and inspire engrossing side projects. They are keen to remind me that my willful ignorance of Godard is not of itself a virtue.

Like few other directors, Varda arouses in her audience a natural affection and loyalty. (I would say that Akerman inspires similar sentiments, but there is an initial hurdle of intimidation to clear with Akerman’s longer and more structuralist works.) We are in relationship with Varda, a relationship that grows with each new film and each rewatch. Sure, this is in part thanks to the on-screen image she cultivated in her four celebrated documentaries of the new millennium: short and zaftig in flowing dresses, her coif a snow-peaked auburn pageboy. She both embraces and spoofs her reputation as the “godmother of the French New Wave.”

Image : https://www.theguardian.com/film/2019/mar/29/agnes-varda-oscar-nominated-french-new-wave-director-dies-aged-90

But Varda’s relatability also stems from her knowability. Just two films in, if that, one readily identifies her personality, her style, her quirks, her themes, her totems. Here’s the Vardian elements that I pick up on and respond to, personally, but please have fun finding your own way through her work.

Agnès Varda’s personality is empathetic yet clear-eyed and hard-nosed. Her style consistently incorporates documentary elements, she’s formally disciplined yet playful, and her films all have a recognizable vibe despite their dramatically different tones.

Varda’s quirks include a penchant for corny wordplay (often untranslatable) that would keep dads worldwide on their toes. She also tends to push her visual tropes to the brink of excess: Think of her repeated use of mirrors to underscore the tension between internal and external “reflection” in Cléo. Or her hyper-ironic use of saturated pastels in Le Bonheur. The checkerboard theme brandished throughout Les Créatures. Even the rigorously employed tracking shots of Vagabond go too far when the steadily moving camera abandons Mona during a moment of crisis.

image from Cléo from 5 to 7: https://theartsshelf.com/2020/05/11/the-criterion-collection-announces-the-complete-agnes-varda-15-disc-collectors-set/; still image from Les Créatures from video streaming on Criterion Channel: https://www.criterionchannel.com/videos/les-creatures

We’ve considered some of Varda’s themes already: Her love of the French countryside and its people recurs again and again. So too her love of the ocean. Her grand theme, I believe, is human ecology. How people relate to the spaces they inhabit and to each other within those spaces. All the forces of humanity and fate and nature that influence these relationships. An extension of this is her interest in people on the margin. Once you’re attuned to Varda’s ways, you understand how human ecology informs her ability to balance empathy and tough-mindedness, compassion and dispassion.

Finally, there’s Varda’s totems, themselves another quirk. Linked to her themes, these are the objets-fétiches, the graphic knickknacks that inhabit her every film. Whenever I watch or rewatch one of Varda’s films, I keep a mental scorecard:

Cats

Ocean

Tree Factoids

Sunflowers

Goats

Potatoes

Varda’s totems tend to accumulate over the course of her career. I’ve no doubt that Varda includes them just because she likes them, or simply because she can’t help herself. But they also signal to the audience that we’re on familiar and friendly turf. Individually, a beach or a potato may signify something or signify nothing at all. “Je ne veux pas montrer, mais donner l’envie de voir.” (“I don’t want to show, but to arouse the desire to see.”) The totems are there to welcome us to each Vardian experience and to invite us back to the next one.

NOTES

[1] Alexandra Schwartz, “‘While I Live, I Remember’: Agnès Varda’s Way of Seeing,” The New Yorker, March 30, 2019, https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/while-i-live-i-remember-agnes-vardas-way-of-seeing

[2] Michel Marie, The French New Wave: An Artistic School, trans. Richard Neupert (Malden, Mass., and Oxford: Wiley‑Blackwell, 2002), 12.

[3] Ginette Vincendeau, La Pointe Courte: How Agnès Varda “Invented” the New Wave, January 21, 2008, https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/497-la-pointe-courte-how-agn-s-varda-invented-the-new-wave.

[4] Now the MK2‑Parnasse, owned by the production company MK2 founded by the prominent producer Marin Karmitz, who served as an assistant director on Cléo from 5 to 7. Eric Smooden, The Paris Cinema Project, June 9, 2016, https://pariscinemablog.wordpress.com/2016/06/09/the-paris-cinema-project-15/.

[5] Richard Neupert, “Certain Tendencies of Truffaut’s Film Criticism,” in A Companion to François Truffaut, ed. Dudley Andrew and Anne Gillain (Malden, Mass., and Oxford: Wiley‑Blackwell, 2013), 242–264.

Edited by Michelle Baroody

Terry Serres is a plant nerd, year-round bicyclist, unrepentant Francophile, and devoted dog dad. He works as a restoration ecologist for Landbridge Ecological. Like Agnès Varda he is a purveyor of tree factoids. He’s waited a long time to watch on the big screen the films in the Varda series. His Letterboxd handle is CineQuaNon.