|Tom Schroeder|

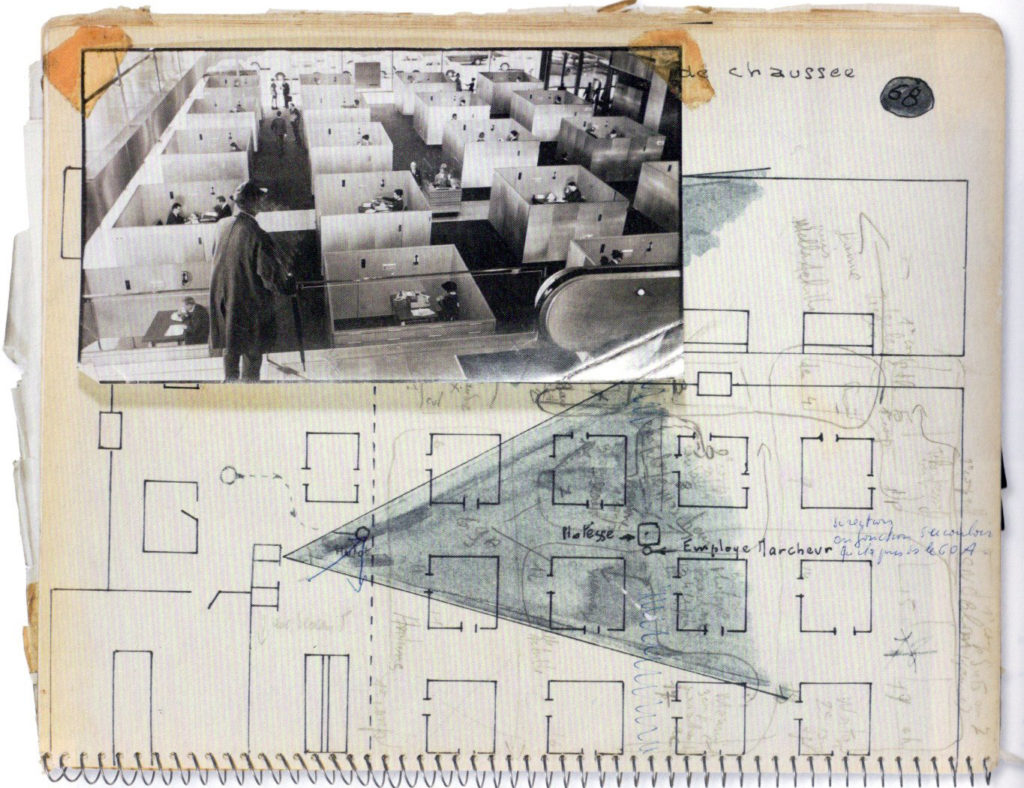

If one considers a movie as a window opening upon a discrete panorama of life, then Jacques Tati created perhaps the most wonderfully compelling view I know in his 1967 masterpiece Playtime. He built“Tativille,” a small facsimile of modern Paris on the outskirts of actual Paris, in which he shot his uniquely stylized mime for three hundred and sixty-five days. On the surface, Playtime addresses a specific style of mid-twentieth-century architecture and the dehumanizing effects of such rigidly rectilinear buildings upon the inhabitants. But within these confining, malfunctioning spaces, Tati stages not one foreground narrative, but multiple layers of incidental action, in which characters are introduced with broad gestural strokes and then reappear later as their paths through the maze intertwine with those of others. In a film composed on widescreen 70mm and lacking close-ups that might direct our focus, Tati gives the viewer agency to direct their individual journey through his complicated tableau. And in this manner, Playtime also implicitly proposes a form of observation by which urban dwellers might transform their environment outside the theater through active visual play. In a bewildering contradiction, this film, constructed by means of an airtight artifice, ultimately represents life as it’s lived on the streets with a verisimilitude equivalent to the spontaneous films of the “Cinema Verite” and “Direct Cinema” movements. I’ve seen Playtime more often than any other film and the delightful method of Tati’s observation has made the transition fully from the movie theater into my daily life.

My introduction to Jacques Tati was Mr. Hulot’s Holiday in a college film club screening at Lawrence University in 1982. I recognized Mr. Hulot as a descendant of the silent-era, slapstick comedians and the gag structure of their movies. Tati modernized the genre, however, with expressive use of post-production sound design and surrounded the humor with an unusual atmosphere of detachment and mild melancholy. He held the audience at a distance from events, deemphasizing conventional narrative structure and emotional identification with the characters in the film.

A good example of a device that Tati repeated and refined throughout his career occurs when two characters greet each other in Mr. Hulot’s Holiday. We see them initially in a medium range establishing shot, reaching to shake hands. Water suddenly spouts from a drainpipe at their feet and they spin, hand in hand, to avoid it. The film cuts on this movement to a much wider framing, the original motivation for the action now unreadable, and it appears to me that the two men are square dancing. There is a final spatial cut in which we see Mr. Hulot poke his head out of a skylight window like a gopher; he’s holding a water pan that he has just emptied and is thus identified as the unwitting author of the dance. By means of this calculated spatial remove, Tati abstracts behavior from the context of its recognizable social meaning and allows us to regard it with comic detachment.

I was introduced to Playtime in the late 1980s with my first wife Sayer, during the early days of our marriage. I don’t remember in which theater we watched it, although I do remember that we saw it projected on 35mm film. I initially responded to the strangely “sci-fi” art direction, the meticulous staging of architectural space, and the exaggerated post-production sound that reminded me of an animated film. But Playtime ultimately didn’t depict the physical world for me as much as a state of mind, recognizable, yet formally contained. The represented space of the film belonged more to an imaginative ideal than it did to waking life; “Tativille,” too, existed in the mind.

Sayer and I were so impressed by Playtime that we checked out a VHS tape of the film at the public library a few days later and watched it again. We invited friends over to watch it with us a third time and I was surprised that some people found the film alienating. About ten minutes into the tape, a woman asked with a mixture of guilt and irritation, “Is something supposed to be happening?” I realized then how well-conditioned we are as movie-viewers to be guided by a protagonist through a single foreground story. I also understood that Playtime was uniquely designed for the large screen and that its full impact depended upon that scale; one needs to be visually absorbed in the film.

I’ve subsequently seen “Playtime” at least twenty times, most often in movie theaters. When the Trylon Microcinema last showed the film in February, 2018, I watched it on Friday, Saturday and Sunday evening. I even travelled to Paris specifically to see a restored 70mm print in the fall of 2002. Tati’s film rewards repeated viewings because it is constructed Breughel-like, both in depth and laterally, in multiple layers that he intended us to investigate “democratically” at our own discretion. During the long Royal Garden restaurant scene, I can count sometimes five or six layers of character development within a single shot. The film is literally playtime for our eyes and ears as we follow these multiple threads through the “Tativille” set. Because of the overwhelming generosity of information in Playtime, it cannot be comprehended in one viewing (or two or six or ten, for that matter). With each screening the curious audience member, willing to accept their responsibility as the current director of Playtime, creates a particular experience of the world that Tati has invited us to enter. Even after twenty viewings, I’m still discovering new details in the mid and deep background layers of the film and I’m constantly impressed by the precision with which Tati handles the overlapping visual continuity.

Eventually, I learned that the experience of Playtime extends beyond the confines of the movie theater when I carried a similar framing of observation into the world outside; Tati ultimately teaches the audience his way of seeing the city as a performance. Film writer Jonathan Rosenbaum describes this education:

And, not surprisingly, I found I could apply this lesson more readily to Paris, with its outdoor café chairs that function as orchestra seating and the theatrical lighting of its streets at night. Playtime proposed a particularly euphoric form of reengagement with public space, suggesting ways of looking and finding connections, comic and otherwise, between supposedly disconnected street details—not to mention connections between those details and myself. (Rosenbaum, 2009)

This implication of the film’s power was clearly intentional. In the original script for Film Tati N˚ 4, the movie ends with a never-shot, bookend scene in the Orly airport:

At this point, all our characters are transformed into shadows whose figures are silhouetted against the uniform surface of the décor. This stylization only emphasizes their personality by emphasizing the different ways in which each puts on a hat or wears too tight or too loose a suit and their different ways of walking. These shadows, each with its own individuality, multiply and soon overflow from the screen itself and are projected onto the walls of the auditorium. (Tati, LeGrange, 1967)

There is no explanation as to how this effect was to be created in the individual theaters, but Tati clearly imagined his film transcending the boundaries of the screen upon which it would be projected, at least metaphorically.

When I met my present partner, Hilde De Roover, in the early 2000s, one of the first movies we watched together was Playtime. We immediately developed a ritual based on the film that, I believe, would make Jacques Tati proud. Whenever we are in a city with an adequate drama of street life, we watch Playtime (or if one were to be strictly literal “play Watchtime”). We choose a bar or coffee shop with a large window that overlooks a busy street, order a drink and sit to observe the movie. Initially, the scene is fairly banal and random. Anonymous characters enter and pass through the frame. But suddenly a meeting occurs; two people gesture to each other and stop to chat. Then one of us recognizes someone who has passed through the frame earlier, walking back through in the opposite direction with a shopping bag and a kernel of scenario is introduced. Our intent concentration begins to impose meaning upon a manner of walking. A limp has a motivation, a heavy swaying gate communicates a mood and a glance up at a window in a building has significance for a character. With patient focus, the random flow of street life is organized into a dance, with everyone a potential Hulot.

On one occasion, we were eating in an Indian restaurant on Second Avenue in the East Village in New York, watching Playtime. Hilde excused herself to go to the bathroom. I was concentrating on a one-legged bicycle messenger, who struggled with a bag over his shoulder, when I saw a fashionable woman walking with parisienne flamboyance behind him. A Tati-like jump of detachment from the scene followed when I realized that Hilde had secretly entered the movie. Her prank introduced the notion of meta-Playtime, in which we are also performers in the movie.

Certain cities have been ideal for watching Playtime: New York, Chicago, Brussels . . . Paris, naturally, but I think the most rewarding city in which we’ve experienced the film is Buenos Aires. One afternoon in the San Cristobal neighborhood we found a large window with a view over a tiny park. We ate empanadas and drank Quilmes beer while we observed the movie. I recorded an account of the action later that evening:

Three old women eat lunch on a bench, sharing sandwiches and a big bottle of beer. They get up to leave and my attention briefly strays elsewhere on the street until I realize that they are unpacking the magazine stand by the park. It unlocks and folds out like a wooden toy to reveal display shelves for magazines and newspapers. One woman opens the stand, one sets up three folding chairs along the fence by the park and the third hurries back into the park with a hose and plastic bowl to a concrete basin set in the ground. The woman lowers one end of the hose into the water and induces the water to flow through the hose by scooping the surface with the bowl, shaking her hips comically in the process. The woman who set up the chairs is sweeping dog shit off the sidewalk; there’s always a lot of dog shit on the sidewalks in Buenos Aires. Once the detritus is cleared, the woman with the hose returns, squirting soap onto the sidewalk and watering it down. She then attacks it vigorously with a broom, scrubbing it clean. (Hilde and I begin calling her “Mama De Roover” after Hilde’s mother, who also has a mania for cleaning.) When she finishes with the sidewalk, she returns to the park and starts cleaning the paths and watering the plants, aggressively chasing everyone out of the way. Old men on benches first lift their legs to avoid the water and then sheepishly fold their newspapers and move to another bench or leave altogether. This woman intends to have the cleanest spot in the neighborhood. Finally, the three women sit down in the chairs and began to greet old men walking in the neighborhood, who stay to talk with them. In the two hours that we watch them, they sell one newspaper. (Schroeder 2012)

I like to imagine Jacques Tati lingering in bars and restaurants, studying the physical mannerisms of people, collecting material like my notes above as a starting point for his mime and then shaping his people watching into vignettes for his films. As he once described his process, “Filmmaking is a pen, paper and hours of watching people and the world around you. Nothing more” (Tati, 1971). Playtime may be considered a grand window through which we view a collection of these vignettes, organized thematically. Indeed, it is a construction of many windows within windows capturing and reflecting multiple layers of perception in a wonderfully complex aesthetic space. But Playtime is also simply a manner of seeing, a state of mind resultant from the experience of the movie. Tati’s final genius as a filmmaker is to transfer his eye for heightened gesture and situation to you, the viewer of his films. As his willing student, he taught me how to transform my own environment through this act of directed attention, curiosity and play. Start your own education May 28 – June 1 at the Trylon Microcinema––watch it every night!

Playtime screens from Friday, May 28 to Tuesday, June 1 at the Trylon Cinema. For tickets and more information, please visit trylon.org.

Edited by Michelle Baroody

Works Cited

Jonathan Rosenbaum, The Dance of Playtime, (The Criterion Channel, 2009).

Jacques Tati, Michel LaGrange, Tati Film #4, (Taschen, Germany, 2019).

Jacques Tati, Interview 1971, (Taschen, Germany, 2019).