| Ryan Sanderson |

Sherlock Jr. screens with Rumble in the Bronx at the Trylon from Friday, September 24 to Sunday, September 26. For tickets and more information, scroll to the bottom of this page.

Perhaps you know someone who is resistant to films outside their comfort zone: someone who says they don’t watch black and white films, don’t watch films with subtitles, don’t watch things made before 1977 (maybe 2007)? And I mean, there’s nothing technically wrong with that person. Our viewing habits are just that—habits—and each of us has to negotiate our own balance between challenge and comfort to get us through our lives. But suppose that person offers you one shot to prove them wrong. They’ll sit down for one movie, any movie you choose, to challenge their belief in this, that, or the other. What do you go with?

Here, I’ll offer my shortlist. Consider your own as I go.

1. Sherlock Jr.

2. End of list.

Now there are a lot of reasons for this choice—we will get to them—but I want to get the primary one out of the way first: I’ve done it many times and it always worked. In college my best friend and I owned at least ten DVD copies between us (the Kino double feature with Our Hospitality), which we loaned out like evangelists distributing tracts. Sure, it was pushy, annoying behavior from a couple nineteen-year-olds, but we were enthusiastic new cinephiles looking to communicate that joy however we could. I’ll also note that nobody who watched the film ever complained. In fact over the last fifteen years I’ve watched Sherlock Jr. with hundreds of people, from large public screenings to my grandparents’ basement, and never once did it fail to absolutely kill.

With that out of the way, there are a few reasons why I think the film works so well on new audiences. You need to start with the biases against silent films in general: they’re slow, they’re boring, they’re melodramatic, they don’t shake the camera enough to keep my lizard brain happy, they’re paced for people who read multiple newspapers a day for fun. Whatever someone’s apprehensions about Citizen Kane or L’Aventura, the gaps between those films and modern audiences are nothing like the gaps between us and The Phantom Carriage, exponentially so given how radically the medium and audience expectations evolved during the first third of the twentieth century. If you want to open someone up to cinema on the whole, from Altman to Żuławski, what better way than to show them something that challenges every stereotype in the most stereotyped of mediums?

And I can’t think of a film from any era that stands in such stark defiance against all that scares people about silent film as Keaton’s indefinable forty-five minute wonder. It’s not just the action or Keaton’s inimitable physical prowess which allows him to pull off gags nobody else would even conceive of. There’s also the spirit of the thing—wry, subversive, paced and structured as though the audience is capable of picking up on a joke in every corner of the frame.

Sherlock Jr. isn’t the most audacious or emotionally devastating film you could show, but that’s not really the assignment. In this hypothetical situation (which I have crafted expressly for the purpose of making a point) you’re only trying to tear down barriers. We all have them, invisible habits that creep into the patterns of our thoughts, inform our perceptions of reality, tint one experience in a flattering light, another as something to be feared. Overcoming those little gremlins is hard for anyone. The whole industry of Hollywood is structured around shaping them. So why not take a film that is so inarguably the opposite of what an audience would expect that, instead of challenging a few individual biases, it devastates the notion that we can predict these experiences at all.

And as a bonus, the movie explores that very concept. Content and concept are inextricably linked. There’s a fascinating relationship between the way Sherlock Jr. appeals to audiences and the way it explores how movies do that on the whole. It ties in with a long-running debate about this film between enthusiasts, like myself––who call it a knowing, self-reflexive examination of storytelling and the human psyche akin to something by Charlie Kaufman––and cynics, who argue it’s a silly, ninety-seven-year-old, comedy short––and obviously that can’t be true, you pretentious goober.

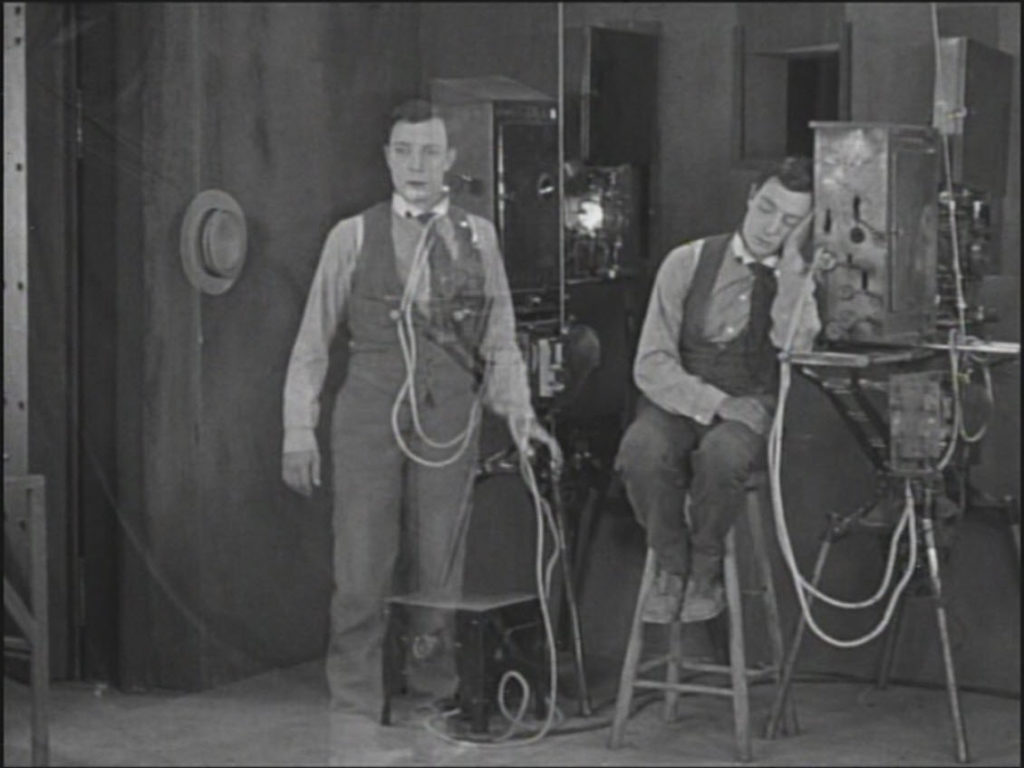

In my defense, I’d like to point to two popular anecdotes about Buster Keaton’s development as an artist. In the first, he’s a small child in his family’s vaudeville act. There was a bit where Keaton’s father violently tossed him across the stage, and he discovered the audience laughed harder at the bit when he didn’t cry or react much at all. Thus, his signature stone face was born. A couple decades later, when he first considered becoming a filmmaker, Keaton insisted on first taking apart a camera and putting it back together piece by piece so he could be certain he understood exactly how it worked.

Both of these stories describe an unnaturally analytical mind, considering every variable, constantly experimenting, and immediately working the results into his art. So yes, I agree Keaton’s primary objective wasn’t to make some grand statement about art. He wanted to make rowdy audiences from Sacramento to Brooklyn howl with laughter. However, his process always involved pulling things apart and piecing them back together. The man who once took apart a camera uses Sherlock Jr. to take apart the whole medium, probe its psychological foundation, and meticulously puzzle it back together with some of the most surreal comedy set pieces in movie history. And I think this process accounts for why the movie feels so surprisingly, disarmingly modern.

The best example I’ve seen of Sherlock’s effect on an audience was at the Ordway on January 19, 2016. I had watched the film on computers, TVs, and personal projectors with audiences of up to 30 people before then, but that was the first time I had ever seen it on the big screen with a full audience. A couple hundred people were present for a double feature of Sherlock Jr. and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, each accompanied by a live original score (written by Steven Prutsman and performed by Accordo).

Caligari wraps, there’s a brief intermission, and the host emerges to introduce the next entry. I roll my eyes a bit. They are clearly bracing this “modern” audience for what they believe might be a challenging encounter with the antiquated sensibilities of silent cinema. They tell the crowd that in the 1920’s, booing the villain and cheering for the hero were commonplace (which was certainly true in some settings), and they encourage the audience to do likewise––sort of like assigning kindergarteners hand motions when you want them to pay attention for a song.

Based on what I’ve said above, I don’t think this kind of thing is necessary. I think it only encourages the sense of strangeness and otherness that makes audiences unwilling to engage with this art in the first place.

The first part of the film takes place in the “real world.” All the gags are built around the banality of real life. Keaton plays The Projectionist who wants to be a detective, but he can’t even successfully take out the garbage. The film’s first major joke involves him needing three dollars to buy a box of chocolates but only having two. (If this were a piece of literary analysis I would harp on the emphasis of the disparity between desire and reality at play in every bit, but we’ll keep moving for now.) His boss despises him. His flirtation with a local girl goes horribly wrong when she believes he stole her father’s watch.

This is the trickiest part of the film, given how willfully slow it is. The audience dutifully booed the villain (a local businessman who framed The Projectionist for the theft) and cheered on Keaton. They laughed a bit at a few gags but altogether they’d been convinced by the intro that they were viewing an antique, not something to truly enjoy on its own terms.

The Projectionist returns to work and immediately falls asleep on the job. In a dream, his dream spirit stands from his post, walks into the movie theater, and jumps into the screen. The audience grows silent. They haven’t been told how to handle this, or the truly surreal sequence (which Keaton achieved through complicated mapping tools) wherein the projectionist tries to navigate inside the film but the screen keeps cutting to different locations. By the time this sequence (more arthouse than pure comedy) fades, the room has fallen completely silent. I smile every movie fan’s favorite smile, knowing what comes next, waiting for the people sitting next to me to find out.

And then the mystery kicks in. Suddenly, The Projectionist is no longer himself. He is the unshakable, utterly perfect in every way Sherlock Jr. His crotchety boss has been transformed into his loyal sidekick and best friend. His paramour’s father––who just banished him from their household––now considers him the world’s greatest detective. He approaches a pool table where the eight ball is booby trapped with a deadly explosive. With hilarious specificity, he proceeds to hit every ball except the eight ball, over and over and over again.

Gag by gag, as the film outsmarts an audience a century more sophisticated, as it appears to parody genres that wouldn’t be invented for decades, the audience, once obviously bored with the film, began to gasp and chuckle. For the last thirty minutes not one boo or cheer could be heard from the crowd; only violent fits of laughter crescendoing toward an eventual standing ovation. I had seen the film do this exact thing so often before, but it was really special to see it on such a large scale.

There’s another hilarious bit (I know I just used that word again––I guess assume all the bits are hilarious unless I say otherwise) during the dream sequence where Sherlock Jr. is on a motorcycle in pursuit of the villains who have kidnapped his love. He approaches a bridge with a large gap in the middle. The audience waits for him to fall into the gap and plummet to his death, but at the last second two trucks drive past, intersecting with the gap in the bridge at the perfect moment so Sherlock’s motorcycle skims over the top of them and continues across the other side.

Cinema is kind of like that. A gap exists between our irrational, unconscious desires and the painfully rational world we live in; a gap that movies try to bridge. Not pure dream, not reality either, but an uncanny middle ground trying to make us believe that our inner fantasies are, if not achievable, at least reasonable.

Which leads to the final scene. The Projectionist wakes up and his sweetheart is waiting for him. She did the baseline detective work he never bothered to, going to the pawn shop and confirming that the true thief of her father’s watch was not The Projectionist, but his romantic rival, The Local Sheik. She tilts her head to the side and waits to be romanced by the boy who, whatever his shortcomings, at least didn’t rob her father for spare change, leaving him to decide what to do next.

He can’t think of anything.

He teeters awkwardly for a moment, and then, in pure desperation, he stares at the movie screen. It’s one of the most famous shots in film history, and for good reason. The film’s larger point––and the reason its gags hit so hard––arrives with total clarity. The Projectionist knows what he wants. He also knows he’s anxious and inexperienced, and he lives in a world where getting three dollars to buy chocolate is a challenge, much less finding love. So he looks to the screen for guidance.

And the screen betrays him! Of course it does! Sure, it tells him how to hold her hand and when to kiss her, and that all goes okay, but then just as it’s getting to the good part, the film fades and suddenly the beautiful young couple on screen are sitting with three babies in their lap. It’s up to The Projectionist to figure out what happens in between.

I know I said before that I don’t think Keaton had any priority besides making audiences laugh, but I don’t know if there’s a better depiction in movie history of the conflict between audiences wanting our entertainment to appeal directly to us and the plain fact that in order for this business of movie watching to be meaningful in any way, we need to put in some of the work. Movies are just one of the two trucks needed to fill the gap between our dreams and reality.

Our dreams may not be achievable or even reasonable, but as Sherlock Jr. has reminded me again and again and again, we still have them together. We, the audience, the individual wrestling with the strange and new, the person next to you whose laughter encourages and bolsters your own, are the second truck necessary to make it all work.

Edited by Michelle Baroody