| Matt Levine |

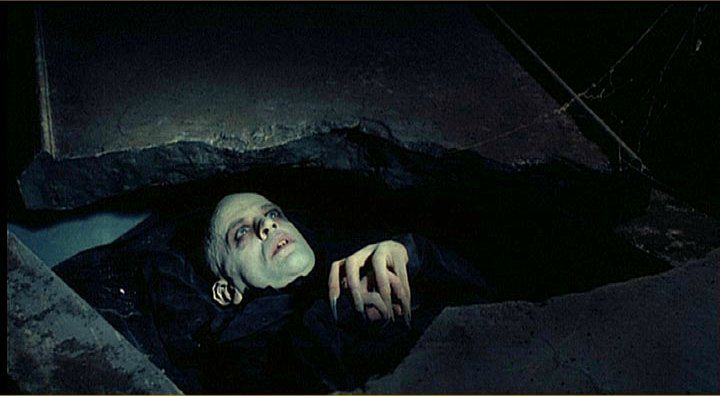

Nosferatu The Vampyre screens at the Trylon from Sunday, October 31 to Tuesday, November 2. Scroll to the bottom of this page for tickets and more information.

These written testimonies were discovered in the personal journal of Count Dracula in the city of Wismar, Germany, circa 1897.

June 12 –

I am the descendant of an old family.

When young, I was told that family lineage could transform one’s life into heaven or hell. Luckily, my family’s wealth and power was such that my immediate existence was heavenly. From our castle in the shadow of the Carpathians, I could roam the plateaus and forests. The sun would warm me, the rain drench me, the snow caress me; they were all my playthings.

My father called our castle a fortress, and he was proud of its dense stone armor. This is the mighty building in which I still live, habiting its frigid hallways at night. When I was a boy, years and years ago (centuries ago, it pains me to say), armies attacked with dreams of conquest. They slit throats and sliced through necks, all for the distant glimmer of power. At five, I watched the woman who raised me—not my mother, who was rarely present—run through with a large, curved blade as she shielded me from marauders who had stormed our walls. I felt love and grief, I know, but what I remember, eons later, is the sight of bright red blood flowing, warm tributaries creating a new topography on my bedroom’s granite floor. Not all was heavenly, I suppose, but even the barbaric moments are tinged with happiness in my recollection.

I am the only one left of my family. The others have died through murder, starvation, guillotine, suicide, plague, and—in a few lucky instances—the calm of old age. There were powerful dynasties formed from marriage between two clans, then more dynasties and more clans, domestic empires. But my whole family was lost, at some point, to the violence of time. We fell into disrepute; we raped, looted, and pillaged; we were overtaken by the peasants we terrorized, who, it turns out, could wield an axe themselves. We could find no more families to marry into, so we stayed within our own, cousins wedding one another, brothers and sisters having children, mother father aunt uncle. This I saw over centuries, till the last one died—a great-great-great-great… (who remembers the generation?) granddaughter taking her last breath. And in her final moment, as she looked past the ceiling and her eyes clouded over, I know now her last sigh was one of peace, not horror.

I am the last descendant of an old family. I was not the only one who was turned; there were both dead and undead on our rotting family tree. But now there is only the dead and me. How I long to join my kin, who once took solace in our family name, though now it can only elicit a momentary shudder, for it is the sound of doom.

June 17 –

Time is an abyss, profound as a thousand nights.

Centuries come and go. To be unable to grow old is terrible. After all this time, I know that there is nothing left to see, nothing left to think. There is a finite number of behaviors, actions, events in human existence. These things roil together, echoes of the past, variations on a theme—a theme which after so many years can only seem like plagiarism.

Once upon a time there were things that surprised me, delighted me. Even once I became the undead, the endlessness of time gave me a giddy thrill. Whatever is new and anticipated becomes a supreme love, once attained. But after its attainment, where else is there to go? The new is a laughable concept: nothing on Earth is new anymore. The anticipated is dashed from the beginning, with foreknowledge of its meaninglessness.

The meaning of endlessness is right there in the word, but stupidly we avoid its meaning. Endless love, endless time, endless joy—these things without end are nothing to savor. Only by knowing the end will come may we enjoy such transient pleasures.

Can you imagine enduring centuries, experiencing the same futility each day? The living cynic will say they can imagine it, not understanding what futility means. Nothing is futile about a human life, precisely because something must be done during the living interval of several decades.

To sink sharp teeth into pliant flesh, to feel a warm gush of blood on my tongue, to feel a body writhe as I take its life into mine—futile, futile. Repeated endlessly. Each soul I meet I know is an imminent victim, but there’s nothing bold in the conquest, no triumph in victory. I close my eyes as I drink their blood and wish I was anywhere, anyone else.

June 30 –

Listen. Listen. The children of the night make their music.

I was wrong, perhaps. I do take joy in some things—the animals. The wolves, the bats, the worms, the rats. Nocturnal creatures that howl, squirm, shriek, or flap their wings, because that’s all they know how to do. I am like them, living without deeper reason, surviving only because I have to do; the difference is, I am aware of my incompleteness.

There are many—the meek villagers, the untold thousands who will be claimed by my plague—who cannot place themselves in the soul of a hunter. They see me, they tremble, they know I must die, but they do not have the courage to plant the tip of a stake over my once-beating heart and drive it through my body. Even the ones who know what I am, they comfort themselves with superstition but don’t take the gruesome steps they know they must take. In this way, we are both incomplete: me in my perpetual shroud, them in their cowardice. Someday, a true soul will finally kill me, the first real human that’s existed in the centuries of my undead life.

July 2 –

I don’t attach importance to the sunshine anymore.

Or to glittering fountains, which youth is so fond of. I love the darkness and the shadows, where I can be alone with my thoughts. Sunshine, light, beauty, they’re all unfaithful to the true nature of the world I know.

This castle I call my own, the shadows which move of their own volition, the rays of the moon cutting through blackness—this is a truer illustration of the world, of living things, of nature’s mad workings.

But to be alone with my thoughts—as I am now, writing words which no one will ever read—is its own kind of torture. Here, too, there is nothing new. Every thought has already been conjured, by me or by someone else. I’ve remembered the infinite moments of my life, its four-hundred-some years, over and over again; my greatest fears and pleasures have been driven down into stale cliché. As if I’m reading an intimate biography of myself, written by a bland and detached author.

I attach importance to the sunshine only because it may kill me. What sweet salvation awaits. And yet, I cannot simply stand in an open window and wait for the dawn to relieve me of my torment. The beast in me insists on self-preservation; this ancient, brittle body won’t let me die.

Once, painters depicted God, the heavens, the apostles, all that is holy; then, the Romanticists turned their brushes to mountains and oceans and deserts, a different sublime. I know that all of this is absurd, that divinity is a comforting myth. And yet (maybe a new thought after all) there might be a God—wicked, cunning, tricking us to disobey our greatest desires. Why else would I want nothing more than the end, though my thirst keeps me going till I may suck down my next meal?

July 11 –

The absence of love is the most abject pain.

Did I ever love when I was living? Perhaps in the way that humans do. But that is nothing, a candle dancing in a typhoon.

When love becomes impossible, the need for it becomes dire. This is no news to anyone who’s loved painfully, desperately, something or someone who detests them, or even worse, doesn’t know they exist.

Sometimes my heart hurts so much, I beat it with my fists. I try to run. But you cannot run from this. It waits for you, like an object of desire that lures you to your downfall. I long for this desire, which will consume me until I feel the rising sunlight upon my face as it flakes into fire and ash.

Can someone love a corpse? No, of course not—whether living or undead, no heart beats within. There is an absence of love within me for this reason. I convince myself that I crave human touch, that I’m driven by ardor, but deep down I know it’s untrue; if a loving soul stood next to me and whispered kindness in my ear, I would bend down and drive my fangs into her carotid sheath.

The absence of love from me, from the world, from everyone—it sounds absurd, but it’s the only logical conclusion. In place of love, there is death—an army of rats, a parade of black coffins, the birth of a new era in which the monstrous is mistaken for the sublime.

Edited by Michelle Baroody