| Yuval Klein |

Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion plays at the Trylon Cinema from Sunday, February 5 through Tuesday, February 7. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

This article contains spoilers. Do not read it unless you have seen the film, or are at peace with the fact that you will not be able to see this film with a naked eye.

The Italian neorealism era of 1940s cinema conveyed social frustration and stories of the working class through realism and minimalism. In the decades after, the face of Italian cinema would gain many dimensions and features that grew upon yet deviated from the standard. Directors such as Federico Fellini, Michelangelo Antonioni, and Luchino Visconti began to create intellectual and dialogue-heavy films that harnessed stylistic, cinematic, and surrealistic hysteria into their portfolios. Early in his career, Fellini co-wrote the neorealist masterpiece Rome, Open City (1946), Antonioni made a short neorealist documentary called People of the Po Valley (1947), and Luchino Visconti directed what is widely considered to be the first Italian neorealist film, Ossessione (1943). The deviating filmmakers of post-neorealism were largely those who had established it as the initial post-WWII voice of Italian cinema.

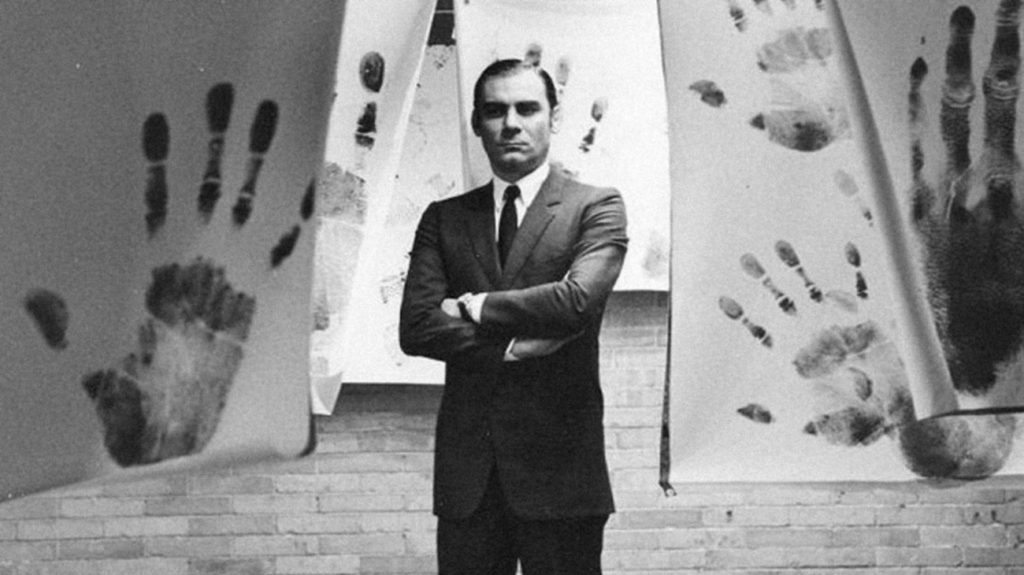

One of the most drastic transformations to come about from the early social realist sentiments were the poliziotteschi (police) films of the 1970s. They portrayed the corrupt law and order system of the time and the political violence that plagued the streets. These stories emphasized violence and urbanity, similar to the earlier Italian art movement of futurism. Many of the stories were conveyed through the lens of sympathetic vigilantes. However, while Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion (I will refer to it as Investigation from now on) follows many of the same themes and subjects, it is also radical in its displacement of them. The film is to the poliziotteschi genre what The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (1966) is to the western: an iconic rearrangement of the genre’s core values. You could call the film “revisionist poliziotteschi” cinema. Both films revise familiar environments (that of urban Italy and rural United States) by placing more nuanced protagonists into the narrative, a narrative that prior to these films would often oversimplify ethical conflicts and good-bad character dynamics. Throughout Investigation, the protagonist appears to be nothing more than a psychopath and corrupt police inspector, but in a stroke of ingenuity, the film wields all of the weaponry built throughout the film to turn its anti-establishment political statements into insights on the ways of humanity, and a more profound allegory of political decadence that was plaguing Italy at the time of the film’s release in 1970.

Before we can dig deeper into the statements that the film makes, you must understand the context of the time’s political landscape. Over a decade, a period of political instability ensued, which is now dubbed The Years of Lead (1968-1982). Dissidents ended up conveying their grievances with the government through outright terrorism. But first, it began with organized protests in 1968, during which universities were occupied by demonstrators. Subversive artists then occupied the Triennale Milano museum for 15 days, a symbolic hijacking of Italian culture. Another early method was labor strikes, which protested working conditions under the shadow of growing industrialization. The first death of the political conflicts was that of a police officer named Antonio Annarumma in November of 1969. He was hit by an iron tube while standing by a union protest. In the following month, the Piazza Fontana bombing made the streets spiral into madness. The bombing targeted the headquarters of the National Agricultural Bank, and it killed 17 people while wounding 88. This was carried out by the right-wing Ordine Nuovo terrorist group that advocated for neo-fascism. However, the unrelated railroad worker and anarchist, Giuseppe Pinelli, was accused of being a perpetrator of the massacre. He was illegally detained by police for over 48 hours, then brought to the office of commissioner Luigi Calabresi for interrogation. Later, a journalist saw Pinelli’s body falling from the fourth floor to his death. His autopsy showed that he was brutally beaten prior. On December 30th, 1969, Pinelli’s funeral procession was met with thousands of mourners. The death was ruled to be a suicide, and thus Calabresi was exonerated from any crimes.

This era of unrest would go on until 1982, but this is the context that led up to the conception of Investigation. Anarchists from the left and neo-fascists from the right were protesting, and in doing so committing terrorist attacks on civilians and politicians. The elite in the police force were corrupt and violent themselves, brutally interrogating innocent citizens. There was an utter distrust between the police and dissidents. As Investigation’s protagonist (I will refer to him by his colloquial name “Il Dottore” from here on out) states in his acceptance speech after being named Chief of Political Intelligence, “They’re alike, the activist and the criminal… In every criminal, a subversive may be hiding, and in every subversive, there may be a criminal.” This is said in the film after a long description of the problems that the anarchists pose; he calls it “an anarchistic plot that means to destroy society. It attacks traditional authority.” This foreshadows what we eventually come to learn about his intentions.

Photo credit: Paolo Pedrizzetti, Corriere d’Informazione, May 1977. A far-left extremist shoots a police officer in Milan.

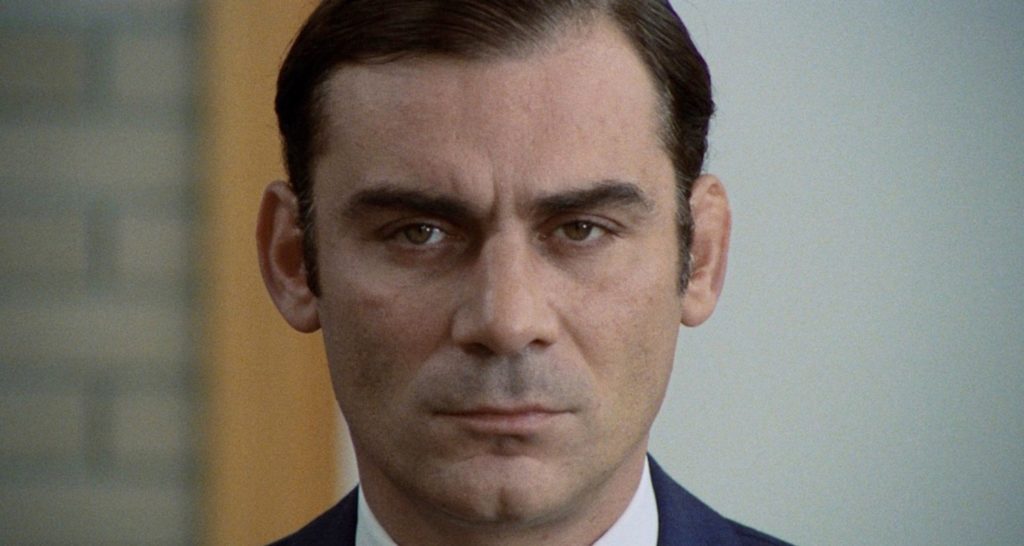

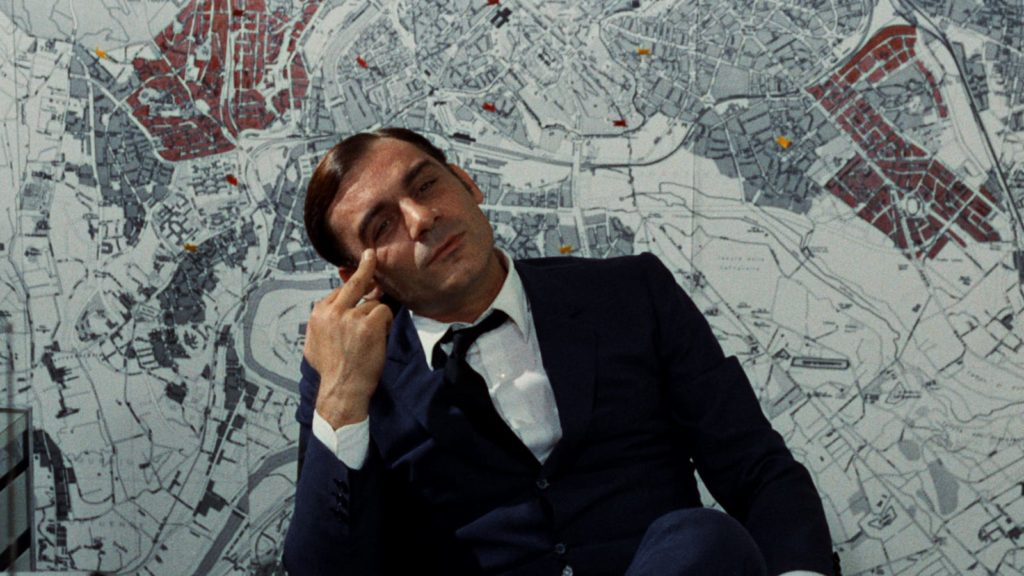

In Investigation, Il Dottore seems to be an apathetic and morally depraved character who attempts to not exactly exploit the system, but tame it like a subservient slave. That is through rising up the ranks and then playing a sadistic game involving murdering a woman in order to see what he can get away with. In a sense, he appears to be corruption personified, whereas the republic is righteous in its values but impotent at enforcing them on him through the law. However, the man who is initially presented to be a perpetrator of a corrupt establishment turns out to have been plotting against the establishment all along. It was his intention to use violence in order to kill one person in the hopes that it would progress his political agenda of dismantling the corrupt system. So, in a way, he represents the anti-establishment anarchists. He weaves through the doors of bureaucracy into a room of the seemingly impenetrable alliance of elite officials. The conclusive event in this room would reveal the cohesion that Il Dottore’s endeavors create as an allegory of Italian politics.

The film ends with a climactic and absurd scene in which the protagonist’s colleagues (members of the elite) gather around in order to confront him on the fact that they have found out about the murder he committed, and then force him to confess to his innocence. The bone-shiveringly authoritative demeanor that Il Dottore maintains throughout almost the entirety of the film is finally broken as he ends up begging for his arrest, and at that point his motives are finally exposed. In his tantrum, he confesses to everything, as he must have intended on doing the entire time, in order to create an insurrection from within the establishment. This scene gives him the duality of contemporary Italian society, comprised of insurrectionists and elitists, both of which adhere to violence. He is the establishment and anti-establishment simultaneously.

In many poliziotteschi films, the sociopolitical turmoil of the time is implied to be Kafkaesque, and thus the stories should arouse a disdain for the precedent of bureaucracy and elitism. This film certainly does so, but with a nuanced portrayal of the anarchist. In a surreal moment towards the end of the confrontation, the protagonist leaves the room in order to retrieve photographs that he personally took, which would incriminate him without a doubt. On the way, he bumps into a hallucination of the murdered woman, who tells him, “You murdered a useless woman. Someone else would have murdered me sometime or another. It was my fate to die that way, you see?” This is moral justification in the perception of violent activists. The woman that he killed was nonetheless innocent, but the prevailing system of ethics at that time was more concerned with larger political agendas than an individual. Il Dottore no longer serves the purpose of representing the malice of the police, as many poliziotteschi films did with such characters; rather, he reflects the “subversive criminal/activist” that he earlier scolded. We are forced to confront the entirety of terrorists not as sadists, nor power-seeking narcissists, nor righteous warriors, but rather as perpetrators of categorically wrong actions that act in the prospect of dismantling a system. If we have considered the actions of the protagonist unethical throughout the film, then why would the fact that his intention was to confront the establishment make the killing of an innocent person right? In this sense, the political agenda of the film is both anti-establishment and anti-violence in general. The larger purpose is to instill Kantian ethics to activists that feel indifferent to any system of right and wrong that does not enhance their “larger” political agendas.

After ripping up the incriminating photographs, the commissioner says about the protagonist: “I always said he had no team spirit. Now look what he’s done to us!” As in the Mafia portrayed in Mafioso (1962) by Alberto Lattuada, the power to exploit and prosper is preserved in loyalty to acquaintances–thus, compliance with the wishes of the few over the many. In juxtaposition with a kafkaesque system, an individual can have absurd power or impotence, importance or redundance.

In the final seconds, the members of the police force go down an elevator with stoic and unrelenting expressions, and it may as well be the entirety of the Italian political landscape on the elevator alongside them. This moment symbolizes the height of Italy as it became not only a republic but a socially advanced one, which then drops into a period of decadence as it regresses back into a more primitive system that increasingly resembles the fascist and monarchical governments that the people had endured until 1946. On top of that, the violence once known in the war is revived. Investigation is a film about a society that is losing its historically remarkable dignity, overwhelmed with divisiveness, and surrendering itself to a clash between fascism, bureaucracy, and anarchy. A quote from The Trial (1915) by Franz Kafka concludes the film: “Whatever he may seem to us, he is yet a servant of the Law; that is, he belongs to the Law and as such is set beyond human judgment.” Throughout the film, this quote proves to be an accurate description of distribution in power. The agenda for both the civil servants and anarchists are perceived as more important than any one person. Thus, a person’s worth is held only in their value to the laws of an agenda, being judged not by their humanity but rather by their loyalty to the ideological system. The Years of Lead marked a new era in Italian society in which the long-awaited years of social advancement and prosperity were finally lost in a Kafkaesque maze of rage and corruption.

Edited by Matt Levine