| Jeremy Noble |

Joe Versus the Volcano plays at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, February 10 through Sunday, February 12. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

“Banks, clothes make the man, I believe that. You say to me you want to go shopping,

you want to buy clothes, but you don’t know what kind. You leave that hanging in the air,

like I’m going to fill in the blanks. Now that, to me, is like asking me who you are, and I

don’t know who you are. I don’t want to know. It’s taken me all my life to find out who I am

and I am tired now.”

–Marshall (Ossie Davis) in Joe Versus the Volcano

There are many ways to look at Joe Versus the Volcano. It can be described as a late example of a certain sort of comedy, complete with two montages, an early performance by Nathan Lane, and three iterations of Meg Ryan. It could be a parable about the ethics of American health care and corporate greed. It could be about burnout. It could be about the cultural fantasy of adventure and how easily people can be talked into lives that don’t serve them. Maybe Joe Versus the Volcano is about all of these things. But for me, it is a very visual story, full of flourishing symbolism.

From the scenes’ lighting to shots of a flower being crushed in the sidewalk, there are a lot of bold visual choices in this film. I was immediately struck by the costume design. In particular, I was taken by the many hats Joe Banks (Tom Hanks) wears throughout the story—literally. While we talk about people wearing multiple symbolic hats throughout their life, seeing this phrase represented onscreen in such a direct manner sandwiches these two layers of composition into one fascinating reason to track Banks’s changes in wardrobe throughout the story. Indeed, hats serve as a most overt tool to establish personal identity for the main character.

When we join Joe Banks’s journey, he works in marketing at a medical device company, awash in cold, fluorescent, and damp gray concrete. His matte black hat is as tattered as his psyche, flat and grim. He has literally hung up his worn, retired fireman’s helmet and traded it for the uniform of a broken man. In his apartment, both hang on a dingy wall as dusty remnants of choices Banks made in his life, as deliberate applications of headwear for different stages of existence.

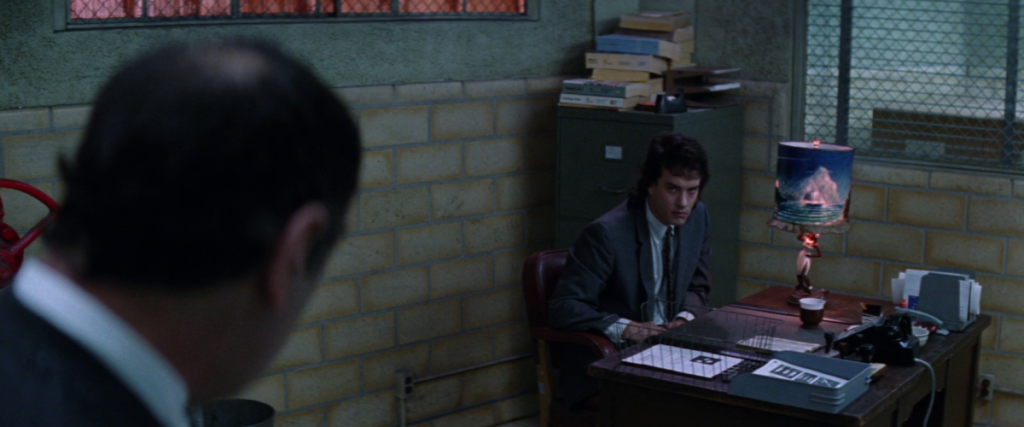

After learning of his impending death during a doctor’s visit, Banks is presented with another choice. He is visited by a businessman who appeals to Joe’s previous life as a fireman. This call to adventure leads Joe to reembrace the heroism he previously exhibited as a firefighter; he decides to sacrifice himself to a volcano. As he decides to change the path of his shortened life, he casts his office hat into the trash. This choice is made easier by a well-funded shopping spree (the first montage of the film). Marshall, a limo driver hired at the last minute, serves as a guide on this shopping trip. He serves as a voice of reason for Joe, reacting quickly to his changing circumstances. Gone are the trappings of the dreary office life—Joe replaces them all with the uniform of the heroic voyager. Khaki adventure wear from Horn of Africa and a jaunty hat steel his resolve for the journey across the pacific.

While Joe has convinced himself that his excessive clothing and accessories purchases have adequately prepared him for an adventure with a heroic end, Patricia (Meg Ryan) complicates his newly found resolve. “That outfit’s wearing you,” she quips, posing a direct challenge to his dress decisions. His jaunty hat is blown off his head, as are his assumptions about any sense of agency he has taken in this new stage of his life.

As Joe and Patricia continue their voyage, they are confronted with realities of lives they have no control over. Joe has been reacting to events rather than making the life he wants to live. Patricia is uncomfortable with the amount of control she’s allowed her father to exert. When a storm destroys Patricia’s yacht, they survive by literally clinging to the accessories Joe has bought with someone else’s money. After the climax of the film, they sail away together, reliant on the same crates.

Costume and accessory choices in this film open multiple questions. Do we choose appropriate uniforms for the life we think we want to lead, or do our hats trap us? Is Banks leaping from one decision that controls his life to another under the guise of controlling his own destiny through clothing choices? Ultimately, the film uses wardrobe as a character’s active point of contemplation to suggest a dichotomy between reacting to or making one’s life circumstances.

When life limits our agency, a change of wardrobe can offer at least some control over how we live our lives. However, that decision can also wear us, and influence how others see us. Think of Angelica, Patricia’s sister (also played by Meg Ryan). While the dialogue between Joe Banks and Angelica mostly plays for laughs, their jokes reveal some truth about superficial appearances. When they initially meet, Joe specifically mentions how fake LA seems, and that he likes it. This establishes a theme of how one-dimensional appearances appeal to characters that are on a quest to find their way through their environment. Indeed, Angelica wears the uniform of an LA woman: shoulder pads in bold colors, sculptural hair, and harsh edges. At one point she says, “I am completely untrustworthy… I’m a flibbertigibbet.” One gets the sense that she is also worn by the outfit she has chosen.

While film is an inherently visual medium, Joe Versus the Volcano uses the language of fashion to illustrate the idea that changing style reactively is far different from the proactive change many of us search for. Even a well-funded, montaged shopping trip is not enough to adequately change our lives. Rather, it makes us tired.

Marshall is right: it takes a lot of time to figure out who you are, and a lot of clothes. “Clothes make the man,” then, cuts both ways. Our outfits can wear us just as easily as we wear them.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon