| Azra Thakur |

Shaft plays at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, August 4th, through Sunday, August 6th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

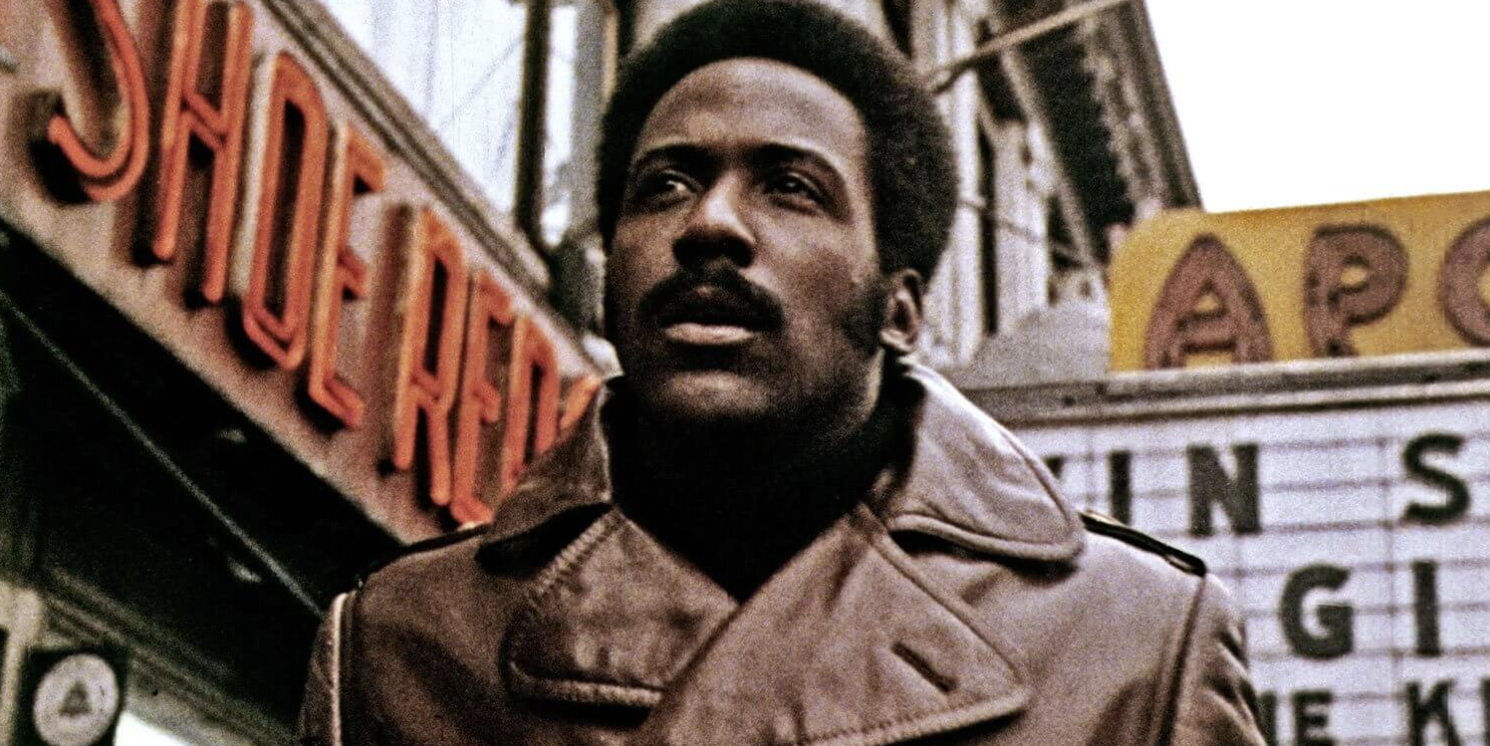

It’s hard to believe Gordon Parks’s Shaft (1971) was released over fifty years ago. Its iconic first scene is still exciting to watch today: from far above, we see John Shaft emerging from a New York City subway staircase to the cold winter outside, set to Isaac Hayes’s perfect theme song, each beat matching actor Richard Roundtree’s purposeful walk through the city. Who is this stylish man? What is driving him forward in life? What are the sounds that accompany him throughout his day? As we contemplate these questions against the beautifully framed documentary-like imagery, we are bearing witness to something new for commercial Hollywood cinema: the Black action-detective hero paired with a memorable soul soundtrack. Emerging from the civil rights era of the sixties, Shaft establishes a defining portrayal for Black actors and filmmakers at the start of the “blaxploitation” films of the seventies and long after.

It is worth noting that Gordon Parks had a long, esteemed career as a documentary photographer before he directed Shaft. Parks started as a fashion photographer in Saint Paul and Chicago, before moving on to the federal Farm Services Administration in 1942, where his photographs of African American life established him as one of our country’s most important documentarians. Parks turned to commercial Hollywood filmmaking much later in life, where Shaft was only his second time directing a feature film.

Dr. Vincent Brown looks at Gordon Parks’s work as a photographer in this short PBS series, The Bigger Picture

While Parks had a well-established career behind him, Shaft offered new opportunities for many Black artists involved in the film. Richard Roundtree’s portrayal of Shaft as a suave man with an impeccable winter wardrobe of sleek leather coats, wool turtlenecks, and elegant suits was, surprisingly, his first film role. Prior to the film, Roundtree had worked as a salesperson in a menswear department and as a model. Shaft was successful on its release, and led to Roundtree starring in many films afterwards, including two sequels: Shaft’s Big Score (1972) and Shaft in Africa (1973).

The film also offered an opportunity for Isaac Hayes to serve as a composer and performer for the soundtrack. Shaft was the first film Isaac Hayes scored. From a sonic perspective, the film takes place a few years after the 1969 Harlem Cultural Festival, as shown in Questlove’s recent documentary Summer of Soul (2021). Listening to the soundtrack in its entirety for the past few weeks on CD, with all its musical complexity uncompressed, makes an afternoon working from home instantly glamorous. Never mind that you are working in the basement with your cat for company—you are suddenly in Shaft’s world. There is the promise of an easeful future ahead, upbeat tones urging you on to your next task, a cool momentum keeping you on track. There’s no stress or fear here; some melancholy, to be expected, but no outright sorrow. It’s mostly sound and only a few words. And by these sounds alone, we know how this story ends—Shaft is going to emerge victorious. It is a celebration of being alive.

In a 1994 interview, Isaac Hayes describes how he was brought on to compose the soundtrack, and reveals Hollywood’s intentions for Shaft. Hayes suggests that the film studio was looking for new audiences to improve ticket sales, and sought Black artists to entice viewers:

Hollywood recognized that they had to look further than they had been looking to get business. I think it was fledgling at the time. It was a bit stagnant… And they said, there might be a market there. If we come up with a concept to have a leading—Black leading man, a Black director, maybe a Black composer, we might hit that market.

Shaft was envisioned by a film studio as a marketing exercise, where Black talent was brought in to improve the film industry’s finances. The film’s storyline doesn’t matter. Parks was someone who understood the power of a Black screen persona in the United States, and how a film’s imagery might transform and reshape a country’s cultural understanding for the better. He would have understood the pitfalls of working within a film system that had no qualms about exploiting his gifts and yet he chose to do so. Hayes, new to the film world, was so effective at conveying the themes of the movie—or maybe it was the other way around, that the music conveyed the themes of the film so well over the storyline—that he received a Grammy for best film soundtrack and an Oscar for best original film song for Shaft’s theme in the year following the film’s release.

Hayes’s performance of Shaft’s theme song at the Oscars is bold. Dancers, outfitted in winning sporty striped ensembles, move along to the song in athletic dance moves. Hayes emerges from a strange tunnel of heads and legs undulating from cutouts, as he rolls across the stage draped in gold chains, shades properly on for the performance, standing over a keyboard playing his song.

Isaac Hayes performs the Shaft theme song at the 1972 Oscars ceremony

The sound of Shaft tells its story, complemented by the images of the film. Roundtree’s charismatic presence, set against the soundtrack, is so strong that the plot and dialogue don’t matter. You can understand the story of Shaft by seeing the images and listening to its music. The film’s world is built on civil rights policy wins and visions of Black power, an escape from the cruel realities Black people in America faced then and continue to face today. We’re watching this film to see John Shaft make his way across the city, a Black man going about his days touched by racism. Yes, this is America. But Shaft’s America is informed by an optimism that feels distant today. Films are a reflection of the time periods in which they are made. In that sense, commercial films especially are an indication of what the industry is willing to take a gamble on. Shaft is going to face his small daily indignities, keeping his cool and staying alive throughout the film.

It’s difficult to imagine what it must have felt like to experience Shaft in 1971 in the movie theater. It would not have been possible to watch it at home until much later, when VHS became a more established home viewing medium. Black action movie heroes are familiar to an American film audience now, especially with today’s ascendant superhero films; but at the time, Shaft would have been a new type of image paired with an energetic, chill soul sound that a Black audience would have been familiar with. Shaft sheds light on the Black stories we get to see on screen in commercial Hollywood films—what stories does the industry invest in and how does it reflect the cultural and societal values of the times? In the 1970s, Hollywood was willing to invest in new Black stories and a sound that had proven to be financially successful for the music industry, buoyed perhaps as well by the political advances that took place at the time. How far have we come since then? How much does it matter if a film is conceived by a marketing team and created by Black talent? Watching Shaft in 2023 reminds us to keep these complicated questions in mind, weighing how much and how little filmmaking and expectations for Black films have changed since then.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon