| John Moret |

The Hideo Gosha, Wandeirng Ronin series plays at the Trylon Cinema Sundays through Tuesdays throughout August, 2023. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

Ronin, noun, historical (in feudal Japan): a wandering samurai who had no lord or master.

On a wintry day in 2012, a friend and I met for our weekly movie and lunch meetup. It was his choice that week and he brought a new release from the Criterion Collection, Three Outlaw Samurai—a 1964 samurai film directed by Hideo Gosha I had not heard of before. As I made lunch we talked samurai films, Kurosawa, and, inevitably, our personal favorite: Sword of Doom.

What unfolded after lunch stuck with me for a decade: Deft storytelling, complicated but lovable characters, and wildly staged action sequences that seemed to unfold with a naturalism that felt alien to my Hollywood action sensibilities. Surely there must be more films from this great storyteller to dive into? Sadly, very few of Gosha’s films were available to see, or show, in the States. Jump ahead to 2023, and imagine my excitement when I open an email from Film Movement saying they have restored Samurai Wolf and Violent Streets for exhibition. Still mostly unrecognized, it is a real treat to have access to these films.

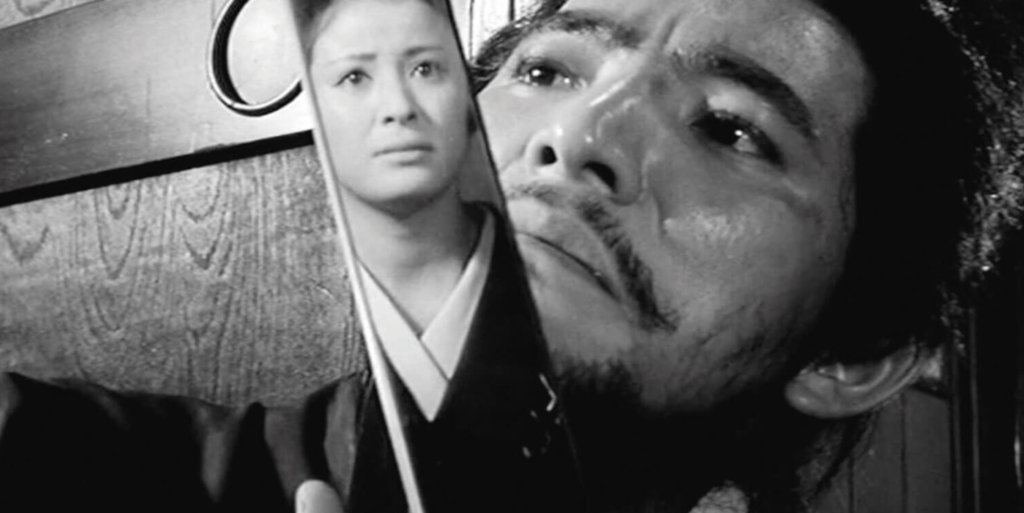

Gosha relied on economy in lieu of painstaking perfectionism, cutting swiftly from one scene to the next and dispensing with all the pleasantries. Samurai Wolf comes in at a brief 75 minutes. It’s lean, mean, and great B-movie fun. A lonely once-samurai (played to perfection by a twitchy Isao Natsuyagi) wanders into a small frontier town in the midst of a feud, playing both sides. Though it may sound similar to Yojimbo (1961, directed by Akira Kurosawa) in plot, the story beats and supremely unique characters are all Gosha—imaginative fighting styles, sparse set design, and eccentric flourishes are distinct from the more well-known Samurai tales.

Even further outside the formula are the truly brilliant Three Outlaw Samurai and comically titled revenge epic Bandits v. Samurai Squadron. These two films, presented on ultra-rare 35mm prints, show the idiosyncratic Gosha perfectly. Exciting and violent with meandering character development, these two films represent a very nonstandard type of storytelling. More akin to late Kurosawa, these stories explore ideas of honor in an age of misguided morality—which Gosha would also apply to the Yakuza genre in his much-lauded but very rarely shown, and finally restored, Violent Streets.

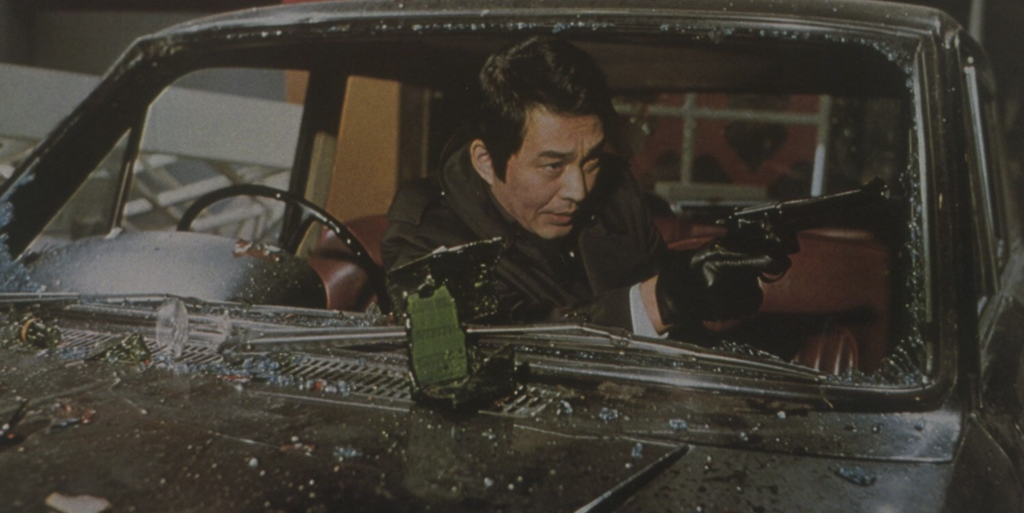

Opening on a freeze frame of rabid dogs behind a chain-link fence with the sounds of a flamenco guitar, Violent Streets moves into a cave-like bar where a composed manager handles an angry customer whose “fancy European jacket” has been damaged. Moving to the side of the bar, Gosha unleashes one of the great character-establishing sequences in the genre. Placing bills of varying sizes on a ticket stabber, the manager then uses the stabber to impale the customer’s eye. Here, Gosha’s flair for a surprising blend of Western music, disjointed imagery, short-hand symbolism, and violent culmination distills his strengths.

After years of watching the films of Japanese masters Yasujiro Ozu, Masaki Kobayashi, and Akira Kurosawa, Gosha’s movies are both jarring and enlightening. You are safe within the hands of the master Samurai. A wandering ronin, on the other hand, has no rules.

– John Moret

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon