| Yuval Klein |

Picnic at Hanging Rock plays at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, September 29th, through Sunday, October 1st. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

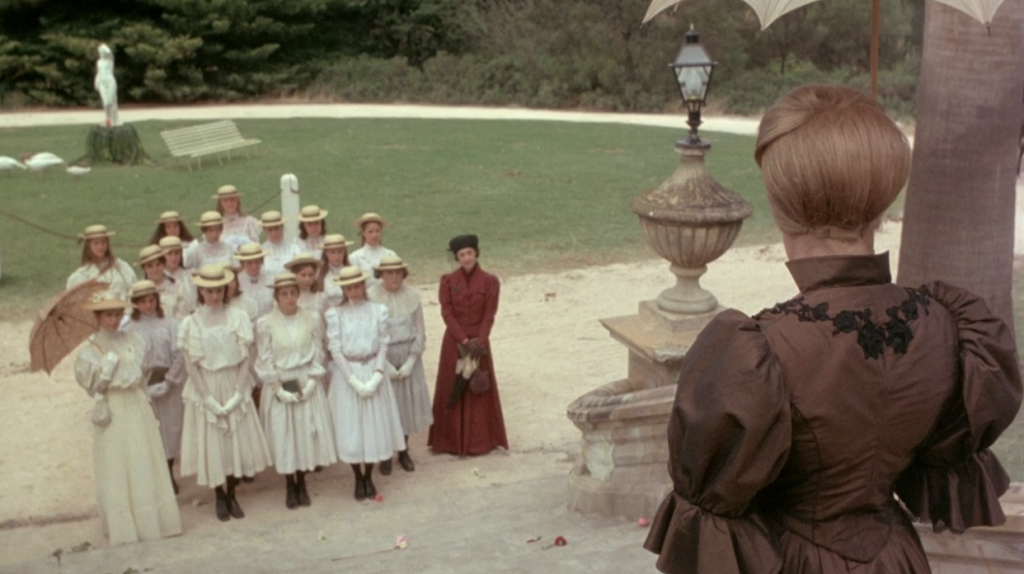

Three students and a chaperone in an all-girls college disappear during a field trip at Hanging Rock, a dormant volcano that has stood in Australia for 6.25 million years. The repercussions as well as philosophical symbols entice viewers for the latter part of the film. Much of the film is set at the college, in which uniformity and “decency” are aspired towards to an absurd degree. In the pursuit of these qualities, all of the women succumb to the inexorable fallibilities of human beings, such as emotional outbursts, unpleasantness, confusion, and so on.

Another pervader of civility that is recurring throughout the film is nature. When the girls are alight behind ominous rocks and a classmate inexplicably screams, it is a surreal and mystical image, but the theme portrayed is that of nature untamed by neither civil society, dogma, nor education. The relationship between humanity and nature appears in a humorous scene in which the lover of the school’s maid is astounded to learn and see that there is a plant that shifts its parts as an animal moves its limbs. When the women arrive at Hanging Rock, the pensive face of Miranda (one of the soon-to-be missing girls) is shown with juxtaposed images of birds zigzagging above. Soon after, a girl says: “Except for those people down there (two young men), we may be the only living creatures in the world. Shots of ants serve as a pillow shot that disproves her remark while showing the pockets of nature that are hidden from the girls and therefore may later surprise them. Nature, in its formidable unassailability, prevails time and again against the contrived British “high society” which is the primary concern of the college. The loss of students and the inability to remedy or undo the repercussions that nature has absurdly brought upon the community is proof of society’s loss to these greater forces.

Another similar theme is that of posture. Sarah, the orphan, is continuously chided about her posture, and is asked to better adjust herself to the uniformity of the school through personality and exterior posture. At one point she is chained to a board that is intended to straighten her back. The board is the symbol of society and more specifically, the school. At the college, women are chained to a rigid idea of womanhood and thinking, but whenever they are inexorably released for a time from the grip of this dogma, there is no suppressing emotion, curiosity, and rebelliousness as they don’t cease to be sovereign human beings forever resigned to the previously mentioned fallibilities. Another motif in the film is umbrellas. The women block the sun and in doing so have a shadow looming over them. The comfort of blocking out exterior influences, among them: nature, boys, and liberation is ultimately undoable and thus unreliable. Out of the four girls that ventured forward, only one of them was wearing a hat, only one returned, and the rest were under the unobstructed gaze of the sun.

When Sarah is told by the insufferable governess that she must return to the orphanage, Sarah smiles. The absurdity of the school is that repression, decadence, and inescapable conformity is what is the product being bought. The most miserable people there are the most wealthy, whereas the maid is the happiest (and freest). She expresses her pity towards the students to her lover, and clarifies that the students trapped in the school are even more pitiful than the missing ones. On the other side of the spectrum is the insufferable governess. The leader of the school who strives to preserve a perfectly stern image also loses her posture eventually (figuratively speaking) as she breaks down crying, and at more private moments, is nearly unable to contain her composure that is only ironed out for her facade of a demeanor in the school. She is the most solitary of all the characters, and her identity is confined to her anglophile bourgeoisie status. In the end, we are told that she has died at the site of Hanging Rock, possibly because she was searching for the girls. However, the audience knows that she did not care for the girls with such fervor, that it is more probable that she commits suicide on the cliff.

The film is based on the novel by Australian author, Joan Lindsay. It was written in 1967, but the story takes place four years after she was born at the turn of the 20th century. Eight years later, it was wonderfully adapted to the screen in this classic directed by Peter Weir. The multitudes contained in the symbolism reveal themselves the more one revisits the film, but aspects of the film remain inscrutable, a striking enigma that is worth revisiting. Also, as we celebrate the work of Peter Weir in this Trylon series, this is a good introduction to his portfolio, as it is his breakthrough film. It is the first of many beloved classics of his, many of which will be screened at the Trylon. This particular film is still very much singular in its memorableness, enduring in the minds of filmgoers for nearly fifty years.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon