|Finn Odum|

Scream 2 plays at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, October 6th, through Sunday, October 8th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

Author’s note: This essay contains spoilers for Scream 2

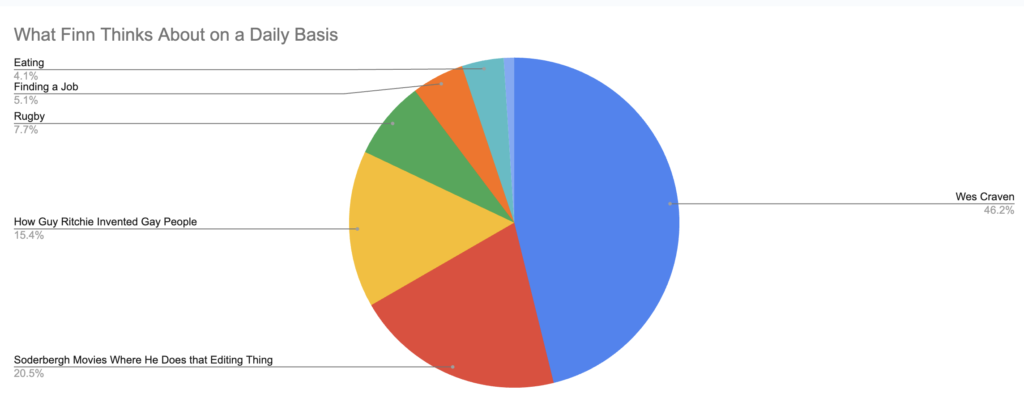

I think about Wes Craven and his filmography a lot more than a stable person probably should.

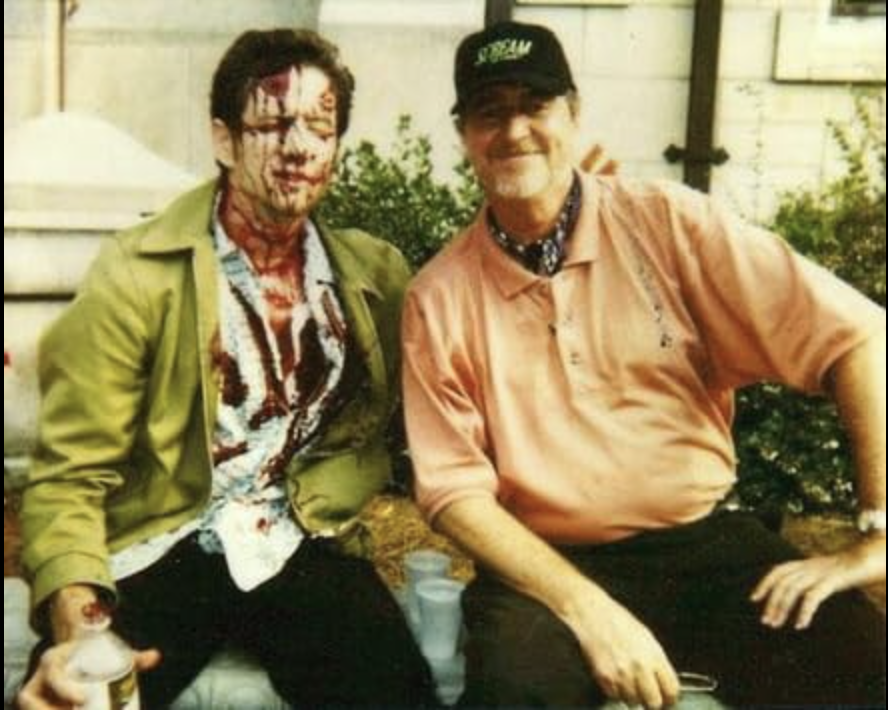

Craven was one of the first directors I followed when I began to study film. It’s partially because he’s a fascinating individual; Craven was an avid birder and a former academic. He graduated from the über-Christian Wheaton College and later became a prolific porn editor. He was a man of many paradoxes, an element that permeated through his fearsome filmography.

He was skilled, too; Wes Craven had an eye for familial trauma, a flair for reality-bending chaos, and an occasionally morbid sense of humor. He (perhaps unintentionally) studied the horrors of the class divide, portraying both the rich and the poor in exaggerated roles of villainy. Craven wrote and directed the tormented Last House on the Left and then turned himself around to write better, stronger, and more empathetic female leads like Nancy Thompson and Kirsten Parker. As a filmmaker, he was both compassionate and unafraid to push social boundaries to a dispassionate degree.

Brilliant and unafraid to break the rules. That was Wes Craven.

And I believe he was fully in the right to kill off Randy Meeks.

The sensational and satirical Scream series was born out of a broke writer and a discounted director’s nightmares. At the time of writing the original script, Kevin Williamson was struggling to support himself financially. Craven was the production team’s last choice for a director – initially passed up for Tarantino, Rodriguez, and Romero—and was only selected after his last horror comedy, A Vampire in Brooklyn, bombed. Though both men were excited about the project, they didn’t expect it to be a success. Upon release, however, Scream made a killing. Audiences wanted more—more violence, more “meta-humor,” and more Sidney Prescott.

And for some reason, more Randy.

People loved Randy. People stanned Randy. He was the underdog, the surprise survivor, the person we relied on to understand what’s happening and why. A character so special that he got his very own extended family in the Radio Silence Scream reboot, because in meta-horror you obviously need someone to point out how meta it all is.

Randy, in my opinion, had it coming.

In the first film, Randy is an expository side character. He explains to the rest of the cast how horror movies work and what they can do (or not do) to survive. Randy is also an audience stand-in; he, like us, shouts at a televised Jamie Lee to turn around and face a killer. We as the viewers are the horror movie experts, living through Randy as he tries to communicate what we all scream at our TVs.

“Don’t have sex! Don’t say you’ll be right back! Don’t expect to live to see a sequel!”

Scream 2, however, is a sequel. And as Wes Craven knows, there are two cardinal rules of a horror sequel: either write out your first protagonist or kill them off. Think Alice in Friday the 13th: Part II, or my girl Nancy Thompson in Dream Warriors. But they’d locked Neve Campbell into a contract, so Sid was off-limits. Dewey and Gale had a weird, will-they-won’t-they thing, which in the ’90s somehow meant they were protected too. So the script went for Randy, the only remaining survivor. Kevin Williamson has gone on to say he regretted killing Randy off, though I’m not positive if it’s because he truly felt that way, or because of the backlash.

Which—yes, there was backlash. Audiences were disappointed that fan-favorite Randy was taken out. Without him, who would relay the major plot points? How would we know that in a sequel, a fan-favorite character would bite it?

Well, we would tell ourselves that. As viewers, we already know the tropes and the archetypes. As much as we’re rooting for the survivors to make it out alive, we’re also riding the tension of knowing one of them won’t. This taught dichotomy is why we consume horror; we live on the rush of adrenaline, inserting ourselves into horrifying narratives and imagining what it’s like to be stabbed from the comfort of our theater seats. With a character like Randy guiding us, we are safe. He’s one of us, viewing the world from our perspective.

When Randy is killed, we’re left vulnerable. We are reminded that we, too, are human. No amount of rules about protecting “final girls” or “slasher survivors” can save us from real threats out there – Ghostface or otherwise. Perhaps another director would’ve questioned Williamson’s original choice to kill off Randy. They might’ve argued to make Sid, our final girl, the first target. But Wes Craven forced his audience to reckon with reality. He dropped Randy into an open space in broad daylight, lured him into a van, and ended him in a violent stabbing.

Wes Craven pushed us to face our own humanity. Randy had it coming—and for such a horror movie expert, he probably knew that too.

I think about Wes Craven as often as I do because his death was the first time a younger me experienced heartbreak. In some way, I treated him like Sidney Prescott. An unkillable mastermind, a strong-willed protagonist. It’s easy to forget that your heroes are also human, that they’re the same flesh and blood mortal that you are.

Like Randy—like Wes—we will have to face our humanity one day.

Edited by Matthew Tchepikova-Treon