|Mia McGill|

Hausu plays at the Trylon Cinema from Sunday, October 29th, through Tuesday October 31st. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information

If you ask someone what their favorite queer comfort film is, you’ll turn back a wide variety of answers; maybe some cult classics like But I’m a Cheerleader or Hedwig and the Angry Inch, or newer faves like Bottoms or Love, Simon.

You’re also bound to hear some answers that you might have to think a little more about; Bend It Like Beckham, Lord of the Rings, even Saw—all movies without explicit queer representation, yet the queer community sees itself in them all the same. I personally consider myself somewhat of a connoisseur of these types of films (and yes, I even have a whole Letterboxd tag dedicated to them).

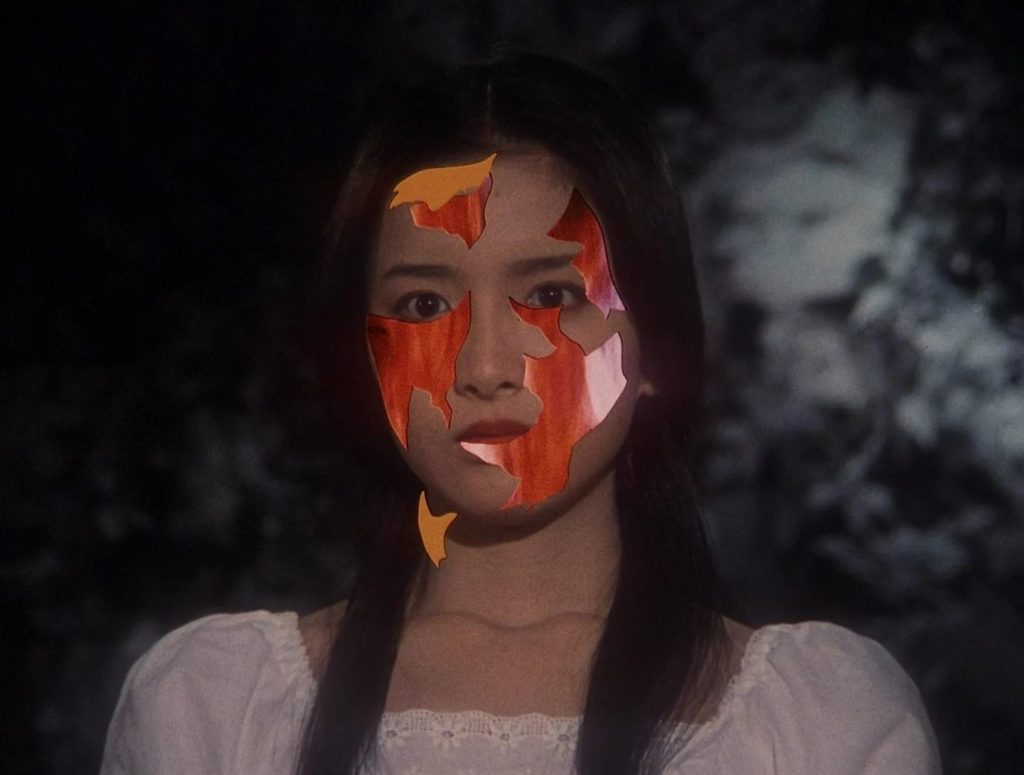

Hausu is one of those movies for me. At face value, a brilliantly garish aesthetic thinly veils some really profound themes of grief and love—Hausu is a vehicle for some pretty obvious queer themes and so much more. Its use of contrast in representations of relationships between female characters creates not only a really well-rounded characterization of its protagonist, Gorgeous, but also a thematically dense story whose sentiments (queer and otherwise) can resonate almost universally with anyone who has ever loved, in any form.

Because of how heavily fetishized female Asian sexuality is, it’s honestly hard to find many popular media representations of Asian female relationships that aren’t bastardized for the male gaze, whether romantic, sexual, or even platonic. As such, I’m grateful to Hausu for the opportunity to see a depiction of many different kinds of love between Asian women in a setting whose main purpose isn’t selling a sexual or romantic story in the traditional sense.

The theme of undying love has been present in countless films and stories for centuries, and will no doubt continue to persevere in the storytelling landscape. But, I think the beauty of Hausu is the different ways this sentiment is treated throughout the story, and the parallels it draws between memory and unfamiliarity in sustaining love.

I.

I see myself in Gorgeous’s grief for the loss of her mother—I never knew my birth mother, and in all likelihood, never will. I grieve still for a life I will never know and a relationship I will never get to have, and a whole range of emotions I will never get to experience.

I found her treatment of Ryoko to be so liberating; the ending of Ryoko burning away as Gorgeous declares that, “the only thing that never perishes—the only promise—is love,” is so succinctly poetic that it hurts. It’s a sentiment I’ve interpreted slightly differently every time I’ve watched the film, but the heart of it remains the same—the reminder that love is immortal, and is carried on in the memories we have of the people we love and have loved us.

While it may seem insignificant in the greater scheme of the sheer spectacle that is Hausu, it validated my fear of change, my anger at things out of my control, and my (perhaps unreasonably) fierce loyalty to a culture and a life I don’t know. Like Gorgeous, I carry those things with me, along with what few memories I can hold onto, in an effort to feel even just a little bit closer to a part of my life that feels so far in the past.

I didn’t get to grow up with an Asian mother figure, or any Asian women at all, really. I was adopted before my first birthday, and I grew up in a Civil War town in Virginia, where pretty much all of the other Asian friends I had were also adoptees. I’m lucky now to have since had the privilege to meet, befriend, and feel so much love from the Asian women in my life—but before that, Hausu let me see and understand this kind of love when I didn’t even know that it was something I was missing.

II.

Gorgeous and Fantasy’s relationship is one I think about often.

Since the first time I watched Hausu, I’ve been fascinated by them—to me, their relationship transcends platonic friendship, and Fantasy in particular reminds me dearly of the way I started to interact with other women when I first realized I was queer.

I could go on about the sapphic subtext in Hausu—I even considered pitching a piece examining Fantasy’s characterization through the lesbian masterdoc—but that’s not the point. Not everything has to be discussed and analyzed and concretely defined as one thing or another; I think there are certain points where the beauty is more in the viewer’s ability to use the implicit as a mirror to their own experiences.

There’s something about their relationship that just feels so personal to me; I’ve often used it as a control whenever I re-evaluate my sexuality every six months or so. Realizing that the way they interact was nearly identical to me in my teenage years, realizing that I could want something like they have with a woman, realizing that I could never have something like they have with a man. There’s something so universal about the carefree and unspoken, yet obvious, love between Fantasy and Gorgeous that resonated with me before I really understood what it meant.

~~~

Hausu has no unearned confidence in telling its story—beneath the layers of campy, over the top editing and effects, there’s ultimately a film with a solid understanding of its characters and some really thoughtful representations of several kinds of love. In its treatment of love as an immortal entity, it too has become immortalized in tens of thousands of hearts, minds, and five-star Letterboxd reviews.

“The story of love must be told many times so that the spirits of lovers may live forever.

The only thing that never perishes—the only promise—is love.”

Edited by Finn Odum