| Lucas Hardwick |

Apocalypse Now plays at the Trylon Cinema from Saturday, November 11th, through Monday, November 14th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

High school…shit; I was still only in high school.

Every day I thought I was gonna wake up and that book report would be done. I’d wake up and there’d be nothing written, and not much read.

I hardly said a word to my sophomore English teacher until I said yes to Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness.

A week passed…then two; that book still hadn’t read itself. Mrs. Brooks looked at me like I had lobsters crawling outta my ears when I chose it. And when I started it, I knew I should’ve gone with The Great Gatsby like everyone else. The fact that this story inspired Apocalypse Now wasn’t supposed to make a difference to me, but it did.

Shit.

Assigning book reports in that place was like handing out chores to a toddler. I never finished it; switched to The Hobbit instead. What the hell else was I gonna do? Whether or not I finished that book at that time remains classified. The bullshit piled up so high at Hopkins County Central, you had to chug a case of Surge just to stay above it.

It’s been over 25 years now and I still have a copy of it. Every year I get weaker, and Heart of Darkness squats in the bush, getting stronger, holding up a pile of books… from the bottom of the stack.

“…my only friend, The End.”

Francis Ford Coppola is a guy who knows a thing or two about not finishing what he starts. It’s the reason why he’s recut the same movie two times over the past 45 years. Originally released in 1979—one of the greatest years in film history—Apocalypse Now was recut with almost an hour of added footage and re-released in 2001 as Apocalypse Now: Redux. Then, in 2019 Coppola removed about 20 minutes of Redux’s added footage and released it again as Apocalypse Now: The Final Cut. Final cut? I guess, but time will tell, won’t it. The finicky Coppola also recently recut and re-released The Godfather: Part III; clearly the man is no victim of “option paralysis.”

Regardless of the varying edits, Apocalypse Now is still the story of U.S. Army Special Forces Captain Benjamin Willard (Martin Sheen) and his mission up the Nung River through war-torn Vietnam into forbidden Cambodia with a scrappy patrol boat crew, where he is to locate and “terminate with extreme prejudice” the command of Green Beret Colonel Walter E. Kurtz (Marlon Brando).

U.S. Army Special Forces Captain Benjamin Willard

Like any other military officer above the rank of Captain—see also, M*A*S*H’s Majors Frank Burns and Charles Winchester III, along with the majority of admirals and commodores in Star Trek—Colonel Kurtz has lost his marbles, and recordings of his rambling, nutty monologues about snails crawling across straight razors and incinerating farm animals not only makes him a prime candidate for President of the United States, but has the Army’s top brass severely spooked. But besides all that, the Army has accused Colonel Kurtz of murder after they received word that he’s executed four South Vietnamese officers who he believed were double agents. Incidentally, all insurgent activity in the area dropped off after the Colonel killed the people in question. And while officers like Colonel William Kilgore (Robert Duvall) are busy “tear-assing around ‘Nam looking for the shit,” catching waves in the name of democracy, Kurtz seems to be the only guy in Vietnam doing his job a little too well.

Kurtz’s past unfolds through searing voice-over monologue as Willard combs the Colonel’s dossier on his journey upriver. The more we learn about Kurtz and his “unsound” methods, the sounder they actually begin to sound, especially in terms of what it means to win a war. I’m not advocating Kurtz’s plight and his godlike status with his Montagnard army, but he begins to make sense in that particular theater of conflict. The Army Special Forces wanted an assassin; Kurtz gave ‘em one, and now the monster they’ve created appears to be diverting from the wholesome causes of the free world.

The heart of darkness, if you will, begins to reveal itself in this film as the level of intensity and commitment, and scary ambition required to get not only the job, but any job done in this war. Much like Coppola’s need to continue to futz with his movies, and my own personal demon that’s haunted me over the past two decades for never completing a heralded piece of classic literature, America’s efforts in Vietnam are explicit, consecutive instances of anxiety-inducing unfinished business.

The film’s theme of incompletion permeates beyond just narrative points and burrows into every motivated intention throughout the story. Broader moments like Colonel Kilgore’s attempt to surf the beaches of the Nung River delta are never fulfilled in spite of blowing the hell out of the surrounding area. In fact, it’s the Colonel’s own orders to napalm the LZ that disrupts the river current and ruins his opportunity to catch any waves at all. Kilgore’s meticulously plotted surf mission sets the bar for the motif of interruption that extrapolates throughout the rest of the film.

“Smells like…victory.”

Chef (Frederic Forrest) and Willard’s excursion for mangoes is rattled by the sudden appearance of a wild tiger. The Playboy Bunny USO event barely begins before horny pandemonium ensues sending scantily clad dancers up rope ladders into a chopper and off into the night. A random inspection of Vietnamese traders gets turned on its head when the high-strung Mr. Clean (Larry Fishburne) opens fire on a sampan during a search of the boat’s goods. No intended task beyond killing is ever completed successfully.

While those are very literal instances of unresolved intentions, business unfinished manifests in the very structure of the film—the movie begins with a version of The Doors’ “The End”—and in lines of dialogue like after Kilgore’s napalm bombing when he tells Gunner’s Mate Lance Johnson (Sam Bottoms), “Someday this war’s gonna end.” Not only is the statement itself nebulous, but it plays like an incomplete thought.

The spooky Do Lung Bridge sequence is a miniature thesis in loose ends as Willard searches pointlessly for the outpost’s CO. Willard asks one hysterical soldier firing 50 caliber rounds into the darkness, “Who’s the commanding officer here?” The agitated soldier replies almost desperately, “Ain’t you?” Another soldier appears with a mortar, determined to kill a Vietnamese screaming at them in the distance. Without any line of sight, the soldier calmly fires the mortar into the jungle killing the enemy. Willard asks him, “Do you know who’s in command here?” The soldier looks at him and with chilling confidence simply says, “Yeah,”—again playing like an incomplete thought—and exits the scene. Conveniently, once back at the boat, Willard informs Chief (Albert Hall) that while the outpost didn’t have any diesel fuel, he managed to acquire ammunition. The very material required to physically advance is not available, but the clear mission of killing is aided and amplified. The entire incident is soul-rattling and serves as a barometer for the escalating weirdness ahead.

Why is Kurtz so scary, though? Willard’s commanders know enough about where he’s at that they can record his batty diatribes, what’s stopping them from committing to all that “extreme prejudice”? Kurtz has it all figured out. What Kurtz recognizes in the then-present military condition is a systemic weakness, and his story of the pile of little inoculated arms he shares with Willard in the film’s final act indicates his humanity yet augments his precision as an assassin. Kurtz clarifies his ideology regarding the capabilities required by men during war: “Horror has a face, and we must make a friend of horror.”

“The horror. The horror.”

The reason these guys can’t get anything done is because they’re more interested in cozy trailer homes away from the front lines. They don’t have briefings, they have family dinners piled high with roast beef and suspicious-looking shrimp. Charlie may not surf, but it’s the priority for the U.S.’s 1st of the 9th Cavalry. Not only do our soldiers receive letters from home, but even the poorest of our troops accept entire tape machines that play recordings of family members reading their letters to them. Willard elucidates the contrast of America’s enthusiastic brand of “police action” against the spartan disposition of the North Vietnamese: “Charlie didn’t get much USO. His idea of great R&R was cold rice and a little rat meat.”

Kurtz is what happens when the task of war is complete, when an assassin has reached the end of the line. He is a man so broken up, his instinct for killing conflicts with his humanity. He would rather talk about gardenia plantations along the Ohio River, but he can’t help but scribble phrases like “Drop the bomb exterminate them all!” Kurtz is not only getting the job done, he is finished business. The phrase “Our Motto: Apocalypse Now” is emblazoned across the entry to his compound, as if anyone wasn’t sure where his philosophy lies. And if you’re not into Kurtz’s poetic brevity, his motto is finishing not just the Vietnam War but all business and now. It’s a proclamation so concisely complete, the half-thought lines of Colonel Kilgore and the flaccid intentions of the Army’s top brass cannot hold a candle to the totality of everything Kurtz represents. If you want to win a war, you gotta be like Kurtz and all for the low, low price of your humanity. For an anti-war flick, it has a surprisingly conservative backbone because Coppola’s message doesn’t diminish war, but rather alerts us to what it requires.

“I am a little man.”

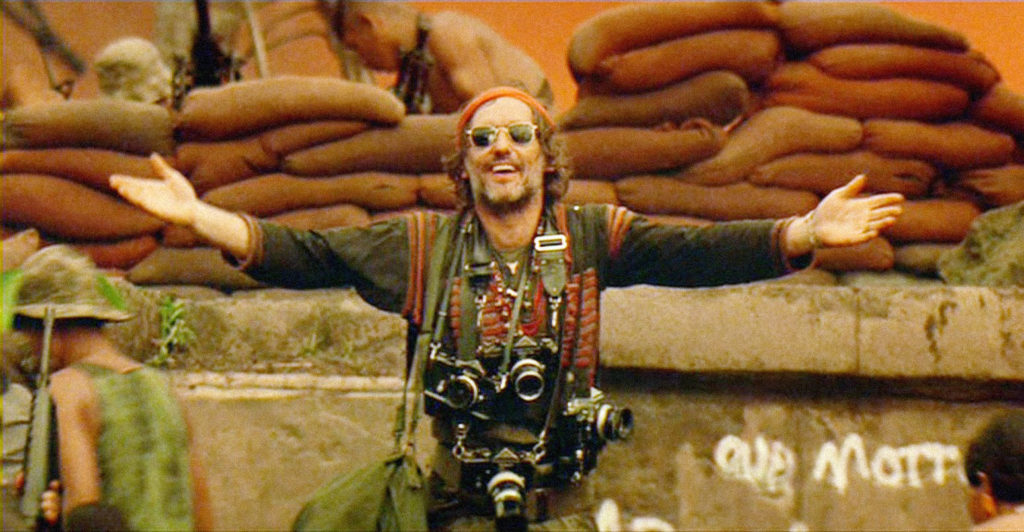

As for me, and most of us, we’re Dennis Hopper’s photojournalist, aren’t we? “I should’ve been a pair of ragged claws scuttling across the floors of silent seas.” We see the brilliance in Kurtz’s ideals, but we are far from psychologically equipped to answer that call. I suppose that means me and Coppola aren’t so different. He can’t leave his movies alone, and I can’t finish a book from my high school reading list. Okay, so maybe we’re a little different, but we are most certainly both human, which will always get in the way of hard-won perfection. The soft edge of humanity ironically overpowers the sharp precipice of completion; not a bang but a whimper is how anything gets done if you’re human. And in that case, it’s “with a whimper, I’m fucking splitting, man.”

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon