| Nick Kouhi |

Hi, Mom! plays at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, November 3rd, through Sunday, November 5th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

It’s easy to label Brian De Palma’s work as an extended exercise in voyeurism. But in a career spanning over half a century, the enfant terrible of the New Hollywood has transcended charges of Hitchockian pastiche with his perspicaciously (and certainly problematic) panoptic cinema, one where the pervasive awareness of a spectral gaze prompts us to modify our sociopolitical identities. Hi, Mom! (1970), was De Palma’s fourth feature, yet I’d argue it was the first to showcase his shrewd ambivalence toward the construction of politically and culturally charged iconography. Not least among these images is the recognizable visage of the film’s then relatively unknown star: Robert DeNiro.

Hi, Mom! was the third collaboration between filmmaker and actor (17 years would elapse before they reunited for the comparatively slicker prestige picture The Untouchables [1987]). Indeed, De Palma was the first American to direct DeNiro in a movie after two uncredited cameos in a pair of French auteur Marcel Carne’s films. Their second feature (the first to receive a theatrical release), was Greetings (1968), a hangout movie akin to a sleazier version of Fellini’s I Vitelloni (1953), where three friends listlessly wander New York City avoiding conscription into the Vietnam War. This film marked the first appearance of DeNiro’s character Jon Rubin, who he’d reprise in Hi, Mom!. In the earlier film, he works in a bookstore and goads an attractive customer into shooting a short film whose voyeuristic perversion is hardly elided. By the film’s end, we see Rubin tromping through Vietnam, confronting a suspected female Vietcong fighter, and ordering her to remove her clothes in front of a war correspondent’s cameraman.

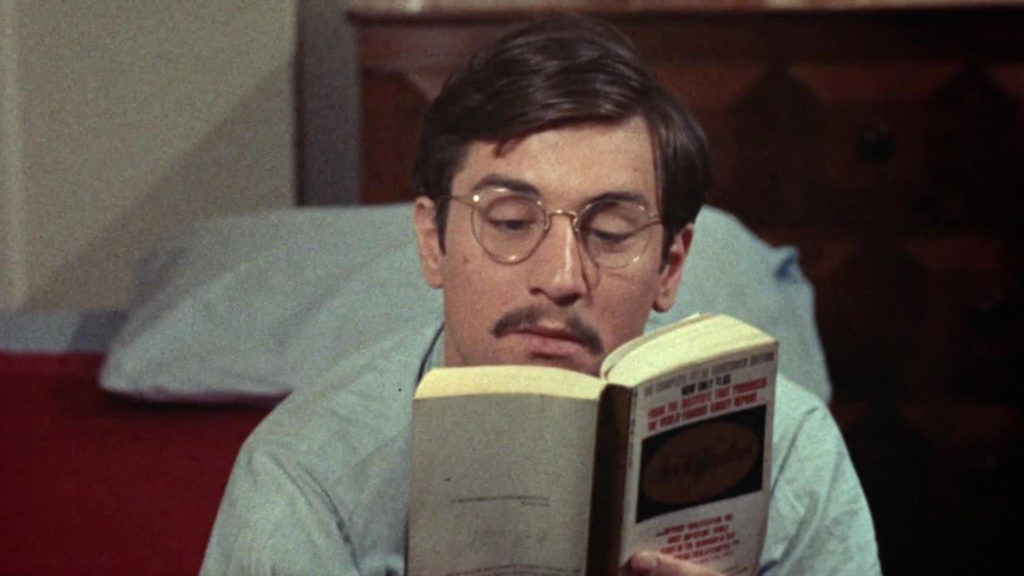

Robert DeNiro as Jon Rubin in Greetings

While too lackadaisical for its own good, Greetings does pack a bitter punch in not only linking popular media with patriarchal imperialism but also ruthlessly identifying how such an ideological incursion is made possible by performativity. Rubin’s sharp commands are those of a soldier and film director, both roles the man can mimic without a shred of conviction beyond his own narcissism. De Niro’s chameleonic assumption of archetypes as armor makes him the protean De Palma protagonist in a corpus riddled with men (and in some cases, women) whose external appearances, and their social roles by proxy, are transformed by choice or force vis-à-vis media apparatuses.

De Palma wisely elevated Rubin to a leading role for the sequel, and Hi, Mom! thrives from De Niro’s deeper entrenchment into performativity, commensurate with the film’s sociopolitical ferocity. Back in the United States, Rubin has settled in a dilapidated apartment whose major draw is the view it provides into apartment windows across the street. He hatches a prurient scheme to initially film his neighbors before opting to woo one of them (Jennifer Salt) into unknowingly participating in a sex reel that he’ll sell to a porno producer (the reliably unsavory Allen Garfield, reprising his part in Greetings).

Rubin’s moral repugnancy is made queasier by DeNiro’s impish buffoonery. The scant pleasure afforded by watching his machinations fall apart is offset by how De Palma foregrounds this anti-hero’s perspective, right from the opening POV tracking shots of Rubin interacting with his apartment’s cantankerous landlord (another character actor giant, Charles Durning). I’d contend Rubin isn’t a surrogate for the audience but for De Palma, who weaponizes his repressed scopophilia into self-incrimination. Yet DeNiro’s presence contrasts with other De Palma-esque cuckolds and patsies, partially due to the foresight of the former’s cinematic legacy. Watching him play a bespectacled “nice guy” over dinner with his neighbor and prey, it’s impossible to neglect other predatory De Niro characters in his work with Martin Scorsese, up to his most recent turn in Killers of the Flower Moon (2023) as the avuncular capitalist casually overseeing the systemic slaughter of the Osage community.

From left to right, Taxi Driver (1976) and Killers of the Flower Moon (2023)

There’s a reflexive quality to De Niro’s performances in the Scorsese and De Palma pictures, which is largely lacking in his mostly execrable output in the new millennium. It’s telling, for example, that the most quoted line of De Niro’s career has been spoofed so often that revisiting Travis Bickle’s ad-libbed monologue is genuinely frightening. In an age where the Internet has enabled incels to indulge and promote their misogynist narcissism, Bickle’s corrosive form of self-actualization is only six degrees of separation from Rupert Pupkin. Jon Rubin prefigures those troubled men as a uniquely disquieting fusion of clown and terrorist.

That latter title is horrifically realized after Rubin takes the part of a cop in a radical activist group’s interactive theatrical production, Be Black, Baby!. The kernel of Rubin’s creative process we glean is his rehearsing in front of a mop before he disappears from the film for a surprisingly lengthy period. Meanwhile, we’re thrust into a performance of the play that immerses and subjects its affluent, white audience to mounting shows of degradation and violence. Filmed on a handheld Arriflex, the Be Black, Baby! segment of Hi, Mom! has been justly praised as one of De Palma’s supreme accomplishments for its visceral (and provocatively political) intertwining of reality with artifice. When Rubin reappears, he viciously beats the patrons painted in blackface, his presence an affirmation of systemic brutality turned against its beneficiaries.

The vicious irony of the piece is subsequently lost on the audience as they exit the warehouse, showering the violable pyrotechnics with bourgeois kudos. It isn’t a stretch to link this disengagement with a depoliticized view of a medium subsumed within a label of “content.” De Niro and De Palma realize a precarious dynamic of separating the real from the fictive through to the film’s climax, where Rubin assumes a dual identity as a middle-class husband and covert operative for the organization. The motivation of his final, destructive act bleakly ties into the film’s title, but this salutary punchline is amplified by how its deliverer modifies his message to the medium. It’s a prophetic vision of myopic image-making that anticipates the echo chambers of social media, where everyone can be a star if they know how and when to wield a camera. Who would think that, at the ground zero of our nightmarish cultural present, we’d find standing there Brian De Palma and Robert De Niro?

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon