| Ryan Sanderson |

Brazil plays at the Trylon Cinema from Sunday, December 10th through Tuesday, December 12th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

One could argue that every Terry Gilliam film is a magnum opus—Time Bandits, The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, The Fisher King, even Lost in La Mancha feels like a definitive statement about human nature in which Gilliam serves as his own Quixotic hero. While other filmmakers of his generation pushed the art form to new depths of realism, The Monty Python Minnesotan made pomposity, grandiloquence, and charlatanry into a brand. He loves nothing more than the aesthetics of a well-told lie, the discovery that any random collection of exaggerations might find purchase in something truthful with the right audience.

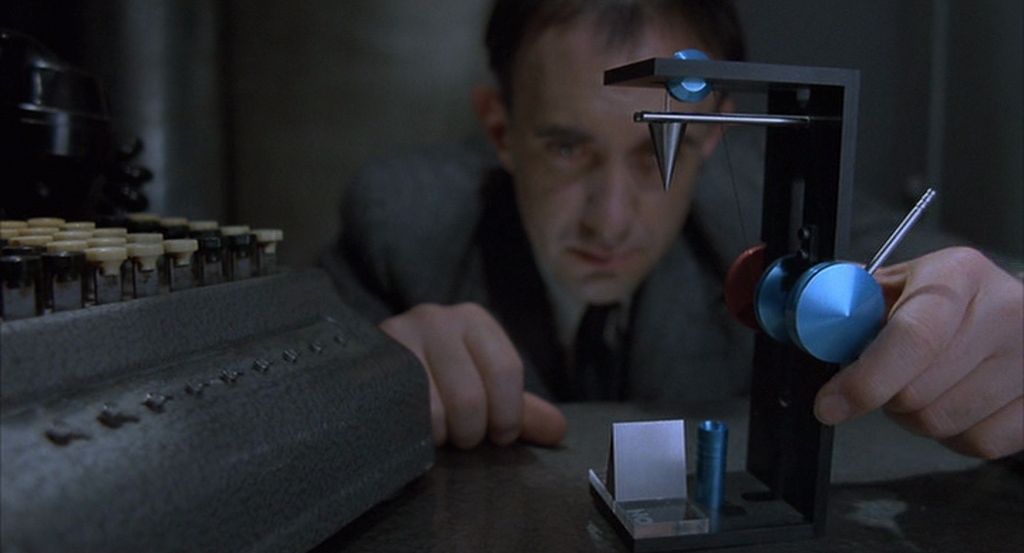

Which I guess would make Brazil his magnum magnum opus—a film about the very nature of magnum opuses. On one side you have “Society” writ in the most aggressively off-putting visual language ever put to popular film, a Boschian nightmare of excess and violence, mysterious tubes and raw flesh splattered about a cold cityscape straight out of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, shot in either sweeping tableaus or high-intensity canted angles like 60’s Batman action scenes or Ron Howard’s Grinch; and then you have “Dreams,” the narcissistic fantasies of wings, monsters, and damsels in distress that grants some purpose to Sam Lowry’s (Jonathan Pryce) otherwise miserable existence.

Lowry is a definitive Gilliam everyman. He doesn’t seem to care about anyone else—even his obsession with Jill (Kim Griest) isn’t really about her, but about her resemblance to the floating princess in his dreams. Content to reside quietly in his more forgiving dreamscape, Lowry rejects promotions and ignores suitors who would pull him further into the dull, grotesque, “real” world. Upon seeing Jill, he makes a split-second decision similar to that of most Gilliam protags–he chases the dream against all reason, wherever it leads, even towards breaking the law.

Almost nobody in the film experiences true empathy. Maybe Robert DeNiro’s Archibald “Harry” Tuttle, a vigilante repairman who swings across the deco cityscape like Flash Gordon fixing air conditioning units without proper paperwork, exhibits some altruism—such that he’s the figure Sam imagines saving him later in the film. But even he cites the thrill as his primary motivation, not genuine care for fellow humans. Jill is depicted as a caring and empathetic human, but the film doesn’t quite know what to do with her. We only ever truly see her as Lowry does, from a distance, as a mysterious figure to be pondered and pined after.

As a coherent worldview, Brazil falls apart. It’s all archetype and splendor, masque and parody. But that’s also not the level on which it’s meant to function. Brazil is the definitive film in a genre I’ve fallen in love with over the years, a parody of the human condition itself, a movie whose primary objective is not to prescribe answers or render new, surprising insights, but to point at the absurdity of this world we’re all born into, full of militarized nation-states, pointless bureaucracy, useless automation, casual cruelty, and dreams. With the filmmakers’ full artistic powers, these films invite the audience to laugh, cry, and scream, “Seriously, what the hell?” together in solidarity. This amalgamation of sentiments finds its origins in Voltaire, Franz Kafka, Buster Keaton, and Samuel Beckett, but arguably reached a pinnacle, at least in terms of expressiveness, with Gilliam’s 1985 masterpiece.

This is why the “Love conquers all” ending was worth fighting against. The point is not that Sam Lowry is some righteous soul we root for to succeed. He’s a bit of a wet noodle, born into privilege, who only started caring about someone else when he wanted to get into her magical floating pants. Of course, his left turn against the state is doomed. But there’s a little Sam Lowry in everyone, the child allowed for a moment to believe the world was all about them, that they were free to pursue their own limitless potential, suddenly plunged into a cold and unforgiving post-industrial, post-colonial nightmare that doesn’t particularly care about anyone so much as its own survival.

Honestly, the best modern corollary I can think of is Greta Gerwig’s summer smash hit Barbie, another absurdist, aesthetically splendorous vision of dream vs. reality in which the protagonist seeks to reconcile these two impossible states–the world as they once hoped it might be, the world as it is. Barbie, a film (supposedly) for small children, ends with hope where Brazil ends with despair, the protagonist ultimately accepting the challenge and uniting with similar individuals to affect change and bring the world back into alignment. Arguably the more Lowry-esque character is America Ferrara’s Gloria, who, exactly like Pryce’s character, is won over to rebellion against the system after she sees the woman she’s been daydreaming about in real life. She’s cynical about the idea of being pulled into a Quixotic adventure, given all she knows about the world, but ultimately goes for it because, “I never get to have any fun,” and discovers that, contrary to her fears, pursuing her dreams actually brings her closer to the people around her.

On the flip side there’s Ari Aster’s Beau Is Afraid, a nightmare opera that also draws huge laughs out of the absurd terror of modern living. The three-hour epic depicts trauma as attic-bound penis monsters and waterbound trials by night. It’s a more focused, even psychologically accurate take on Brazil’s simplistic “individual v society” paradigm, in which Joaquin Phoenix’s Beau is beset (and aided) by several contingents of society, but also by the ludicrous fears projected upon the world by his own inner threat system. Where Gilliam’s dreams always have an aspirational, empowering bent, Beau’s urge him toward fear and sadness, push him further away from being able to save himself. He’s ultimately a victim of society, himself, and his dreams.

Because Brazil paints with such broad strokes, I see it reflected in so many other films, especially those that try to conjure some overarching vision of what it means to be human in the modern world. For instance, The Big Lebowski depicts life as a Chandler-esque mystery in which The Dude (Jeff Bridges) just wants to get by with as little conflict or effort as possible. His dream is far simpler than Sam’s—a new rug—for which he’s pulled into one hair-brained scheme after another, his life cascading out of control. True to their detective fiction roots, both films begin with a case of mistaken identity, resulting in violence and drawing the hero into a quest to attain some form of justice from their society (in Brazil’s case, the search begins with Jill whose cause is eventually taken up by Sam). Lebowski’s campy noir adventure also mirrors the Dude’s (slightly) more realistic relationship with Walter (John Goodman), a Vietnam vet who keeps projecting his trauma onto situations in the Dude’s life and making them much, much worse. And yet the Dude wants to bowl, wants some companionship, so he keeps returning to Walter, just like he wants a rug without urine stains, which draws him to the whole shady cast of characters in the mystery drama. In the Coens’ lower stakes version, life is about how much inconvenience and manipulation you’re willing to accept for the world’s meager pleasures.

One filmmaker who frequently wields a visual metaphor at least as well as Gilliam is Charlie Kaufman, whose own magnum opus, Synecdoche, New York, found a cold, isolated reality in the mind of a self-obsessed theater director (Phillip Seymour Hoffman). Hoffman’s Caden builds cities inside cities all dedicated to himself, while viewing his (ex)wife’s works—which focus on other people’s simpler emotions—as microscopic dots. Every scene where he interacts with someone else becomes poisoned by the addition of his fantasies, which are always driven by his misanthropy and myopia. Eventually even his own inner representations of himself become embittered by his treatment of the details in his world. The film is a deeply cynical (though empathetic) look at the pitfalls of getting lost in your own inner fantasies, however tempting that may seem.

I would argue that Brazil is less insightful than any of the above examples, and yet I love it the most of all of them–probably because, as I mentioned before, insight isn’t what Brazil is going for. Of all these films, it’s the best at inciting reactions, at conjuring nightmares, at drawing huge laughs from some of the darkest, most uncomfortable subject matter we encounter in our lives. Brazil works not because it says anything you couldn’t find in Orson Welles’ adaptation of The Trial, Boots Riley’s Sorry to Bother You, Buster Keaton’s Sherlock Jr., or Jean-Luc Godard’s Alphaville (all of which offer significantly more in certain ways), but because it wields the full might of expressionist cinema towards its singular objective, steamrolling past all nuance and objections to provoke an overwhelming shared reaction. It works so well because it comes from a storyteller who cares less about what he’s saying than how it’s said.

That approach works better in some cases than others–see the last two decades of Gilliam’s career–but in this specific instance, Brazil is the definitive parody of the human condition because it’s lowkey a parody of the parodies, metaphorical past the point where the metaphors have meaning, writ in dance and color, raw majesty and the broadest imaginable sight gags. It doesn’t feel the need to sell you on the premise–if you’re a citizen of this deeply broken world, you’re in on the joke. As a result, despite the violence, the ugliness, that dour, nihilistic ending, I always end the film, like Sam, with something like a smile, having seen all that familiar disillusionment processed through the lens of a master showman, having felt in the most expressive language imaginable, “Seriously, what the hell?”

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon