| Jake Rudegeair |

Singin’ in the Rain plays at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, December 15th, through Sunday, December 17th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

As hard as we pleaded and begged, we couldn’t get mom to take us to Blockbuster every day. In the 90s, we had to rely on the cabinet VHS collection, stuffed with ancient treasures like Key Largo, Terminator 2, and taped copies of whatever dad stole from HBO. Singin’ in the Rain was a load-bearing cornerstone of the library, and we watched the hell out of it.

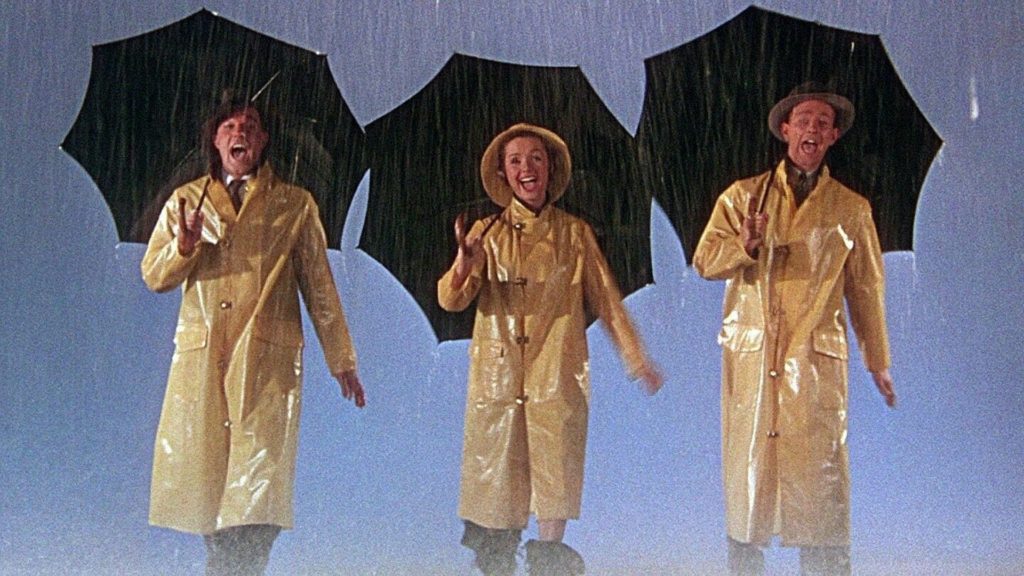

The box art is indelible. It shows Donald O’Connor, Debbie Reynolds, and Gene Kelly in their technicolor rain coats, all wholesome smiles and matching umbrellas. It’s a shot from the opening title sequence, where the three of them bounce towards the camera, singing and marching in time—a manic introduction to their chemistry of contrast. O’Conner is fluid and light. Kelly’s head bobbles like a jack-in-the-box—wound up tight, arm swinging like a metronome. Reynolds saunters like a normal human being, but her elegant voice makes her co-stars sound like dusty bassoons. By the time the extended titles fade in you’re already hooked.

What follows is part romantic comedy, part toothless historical satire, part proper book musical, all oversaturated, all meticulously executed. It’s a tale of Hollywood’s turbulent transition from the silent era to talkies, from the perspective of the talent. The skill on display, from the jaw-dropping dance numbers to the set-within-a-set design to the razor-sharp script to the everything-else, is quite frankly, absurd. The people making this movie were at the tippy-top of their game and it shows.

But as much as I love this dizzying gloss bomb of a movie—as much as it’s fused to my nervous system from a million rainy Sunday screenings—when I watch it now, I can’t help but whiff the elephant dung behind the curtain. We all know by now that Hollywood in the 20s was rife with prejudice, misogyny, and scandal. It’s not that Singin’ in the Rain was a particularly vulgar production (although some scenes haven’t aged well, and by many accounts Gene Kelly sounds like a dictatorial knob), but more that it’s a perfect crystallization of the Hollywood contradiction. At one pole is the pristine film in all its glory, magic, and craft. But at the other is a slop of shattered dreams, avarice, cynicism, and 100 years of depraved idolatry.

Before we dive into the darkness though I have to stop you here for a moment. We can go no further without paying proper deference to the true star of this film, a wonderful Jean Hagen in her role as the impeccably shrill Lina Lamont. This performance is bananas. As the villain she has to be mean, but she also has to be tender enough for us to buy her romantic longing. She has to be powerful while still being relentlessly targeted as the butt of the joke. She’s shrewd and hilarious, and so deeply weird. Her work in this movie is a special and singular piece of art in itself, and the fact that she didn’t win Best Supporting Actress is disturbing.

Where was I? Oh right, ‘depraved idolatry’!

Hollywood hasn’t exactly come through the last 70 years unscathed as a cultural institution. The sociopathic underbelly is well documented at this point. And even as Adolf Green and Betty Comden’s script for Singin’ in the Rain paws at the line between the world of talking pictures and our actual world, it also betrays the fact that a true reckoning wouldn’t be coming any time soon (R.F. Simpson, the studio executive in this film, is just like, a good guy? Outrageous). Singin’ in the Rain is one of the brilliant lies that sold Hollywood to a generation of Blockbuster-starved cabinet hoppers like me.

Fast forward to 2022, and the release of an ardent, brilliant film called Babylon. Damian Chazelle fires his eye at the dark heart of Hollywood. His film explores the excess and the thrill, the nightmare and the luck and the death. It’s set in the same era as Singin’ in the Rain (1926-ish), and is loaded with homage to the legendary picture. It’s taking on the exact same historical conflict too—the desperate, confusing transition to talking pictures. (Spoilers incoming for Babylon)

In Babylon Lina Lamont is reincarnated as Nellie LaRoy, played by an undeniable Margot Robbie. She’s the caustic, magnetic, tragic genius at the center of the story, and the part is no less demanding. She has to yearn and suffer. She has to be incorrigible, full of white-hot fury, ripped on speed, tilting with snakes. It’s a manic performance, markedly kicked off by a cocaine-marinated, body-melting dance number (something they never let Jean Hagan do in Singin in the Rain, to my eternal disappointment).

Lamont and LaRoy are both partially based on silent-era star Clara Bow. Much has been written on Bow as a premier “it-girl” of Hollywood’s “golden era,” as well as her torment at the hands of basically everyone. The heartbreaking story of her life has been carelessly recounted over the years. Leave it to the malignant circus of the tabloids to reduce and sensationalize the lived experience of human beings.

Singin’ in the Rain is fictional, but you can smell the stink of judgment that clings to the Lamont character. You can feel the haughtiness and the disapproval. There’s an implicit suggestion that people like Clara Bow were not Hollywood’s fault or their responsibility. Lamont is a convenient villain for a musical that balances on her axis of conflict and drops the moral penalties of exploitation at her feet. Despite Hagan’s singular performance, the humanity is missing from the character on the page.

As we all continue to witness the surreal melding of entertainment and life (YouTube, reality TV, and so on) it gets harder and harder to watch films like Singin’ in the Rain without a sinking recognition for the real humans who’ve been discarded by this industry over the years—eaten up, spent, used, and sensationalized. Sunset Boulevard, anyone? It’s exciting to see a filmmaker like Chazelle trying to reckon with what we’ve done. He’s challenging our devotion to the nation of Film, and our willingness to overlook its toxicity.

But of course, ugliness and poison aren’t the whole story. In the ending moments of Babylon, Chazelle deploys Singin’ in the Rain directly into the narrative, pulling back the curtain of his film’s inner machinery. It dazzles and devastates as it plays out on the silver screen-within-the-screen. The experience evokes the universe-spanning rapture of 2001: a Space Odyssey. The moment is bright and effusive and raw. Pure cinematic joy jolts up our brains, suddenly glowing like a dopamine marquee. Film history rushes by while the thundering score pumps emotional jet-fuel into every frame. The culmination of Babylon weeps and cheers for the dilated, fucked up history of movies, while also merging with it, right before our eyes. For any faults you can find in Babylon, the ending is masterful, overwhelming, and beautiful.

Singin’ in the Rain is the kind of cultural leviathan that’s always giving us more to chew on. Chazelle’s amazing film wouldn’t exist without it. It will always be a classic that makes me want to sing, to reminisce, to remember my mom’s excellent taste. And it’s also come to represent the oft-poisonous mixture of creative genius and gluttonous commerce in American culture. It changes shape as our stories change. Even the title is renewed with Chazelle’s dissection. It’s a challenge—to sing in the storm, to celebrate the art and the joy even as the rain pounds down and uncovers our delusions and our blunders, our collective self-deception. It’s a cultural prism that throws different light, depending on which way we tilt it. It’s also just an incredible, unforgettable film; a shimmering, glowing star in the cinema firmament.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon