| Sophie Durbin |

The Long Good Friday plays at the Trylon Cinema from Sunday, December 17th, through Tuesday, December 19th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

When distilled down to one sentence, the plot of The Long Good Friday might go something like this: “An English gangster, two American businessmen, and some Irish nationalists all have a very bad day.” It reads like the opener to a deadpan joke at a party full of twentieth century political science enthusiasts. But how political, really, is The Long Good Friday? It’s hard to tell if there’s a real answer to this question. I’d like to suggest that The Long Good Friday is a perfect thriller that brilliantly positions clashing nationalisms against each other as the stakes rise throughout the action. While no true political stance is discernible, the consequences of sectarian conflict, imperialism, and old-fashioned gang violence are all nonetheless laid quite bare.

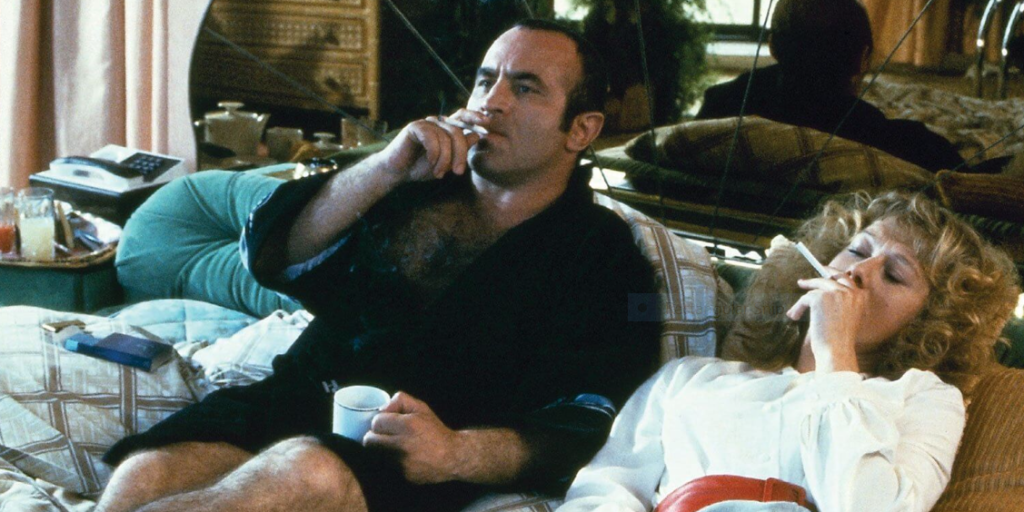

Harold, attempting to obtain legitimacy through an ambitious development deal with an American firm, sees himself as part of the legacy of English greatness. On his boat, the office is decorated with symbols of the empire: maps, globes, swords, and paintings of old ships. The waterfront he plans to build up was once a port teeming with activity. It’s his goal to revitalize the docks as his unique contribution toward making England a “leading European state.” Well-groomed, well-dressed, and poorly behaved, Harold continuously summons up his composure throughout the film to impress his companions. When he welcomes his business-partners-to-be to his boat, he toasts melodramatically to England—and, in particular, to London. We get that he’s a formidable presence, but we also understand that he’s prone to theatrics and self-delusion. His total devotion to England, devoid of class consciousness or any self-awareness at all, really, is both the core value that sustains him and yet becomes his downfall.

Harold’s accidental enemies are members of the Irish Republican Army. Though we spend little screen time with them, every mention of the Irish is met with a pause or a shift in mood, taking the plot Harold finds himself entangled in from tragic misunderstanding to a sinister nationalist revenge mission. The Irish are painted in complete contrast to Harold, unpredictable and silent while he never shuts his mouth. The IRA men’s moral compass is impossible to read. While Harold bellows out orders to members of his corporation after the first bombing, a 25-year-old Pierce Brosnan slinks around a gymnasium pool, playing gay to lure Harold’s friend to his doom. In keeping with his English sense of superiority, Harold never takes the IRA quite seriously enough. When he has the gall to coolly deliver a suitcase of peacemaking cash to the IRA at the film’s end—only to double-cross them moments later—he confirms that the only thing he has reliably done throughout the film is underestimate the seriousness of his situation. He’s punished for this in the final sequence, where Brosnan shows up again and aims his gun at Harold from the front seat of his car. This last ride is perversely pleasurable for the viewer. While we’ve come to root for Harold in a way, he’s been bested by something wilder than he bargained for and the biggest shame is that we don’t get to see what happens next. He grits his teeth, his eyes fill with tears. And though we can’t see exactly what he’s looking at, we have a good idea that he’s stealing glances at the car that kidnapped Victoria ahead of him as well as keeping a steady look at Pierce. He can calculate a business deal, but he couldn’t calculate this.

While the Irish serve as mysterious foils to Harold’s English pompousness, the American business partners, spared from emotional proximity to the conflict, simply raise their eyebrows at the whole thing and pack their bags. In the tense dinner scene with Victoria, the Americans are quintessential New York. Deadpan one-liners bubble up from each of them: “This is like a bad night in Vietnam,” Charlie retorts after Harold brushes off the numerous bombings and murders that sullied their visit. Harold’s final counterargument has a desperate undercurrent, but he delivers it with grave self-importance: “What I’m looking for is someone who can contribute to what England has given to the world. Culture, sophistication, genius. A little bit more than a [h]‘ot dog, know what I mean?” The Americans may be able to walk away, but their very distance from what Harold perceives to be inherent English greatness is what proves them unworthy of the deal in the end.

The grim core coincidence of the film occurs at the beginning, when members of Harold’s corporation go rogue in Belfast, ultimately leading to the death of an innocent chauffeur. During Harold’s later confrontation with the chauffeur’s wife, her grief is visceral. When she inadvertently gives away the whole problem of the plot, Harold immediately offers up weekly payments, saying the corporation will take care of her. This isn’t nearly enough to compensate for her hurt. She wails, “I just want him back,” and it’s hard to watch (calling all character actress fans: Pauline Melville gives a stellar performance here that should be remembered). When the camera lingers on her anguished face, it feels like relief when the scene finally cuts. This prefigures the long shot of Harold’s face at the very end of the film as he realizes what he’s really gotten himself into. One is reminded of the somber tone of Odd Man Out, which offered a similar slice-of-life approach to the consequences of Irish conflict thirty years prior. In both films we catch a simple truism rather than any moral angle: in times of political conflict, it’s everyday people who pay the price.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon