| Timothy Zila |

Brazil plays at the Trylon Cinema from Sunday, December 10th through Tuesday, December 12th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

When we meet Sam Lowry, the protagonist of Brazil, he’s flying. High above the clouds, clothed in a plastic-looking breast piece borrowed from a cosplayer’s wardrobe and feathery wings fit for a campy theater production. There is no clear purpose in his flight—a constant feature of the reoccurring dream sequences in the film—but there is something that catches his eye and captivates his imagination: a woman, encircled by a veil. Lowry flies close to the woman, and closer still, but she remains evasive. He wakes to a phone call and the revelation that, due to faulty electronics, he is very late to work.

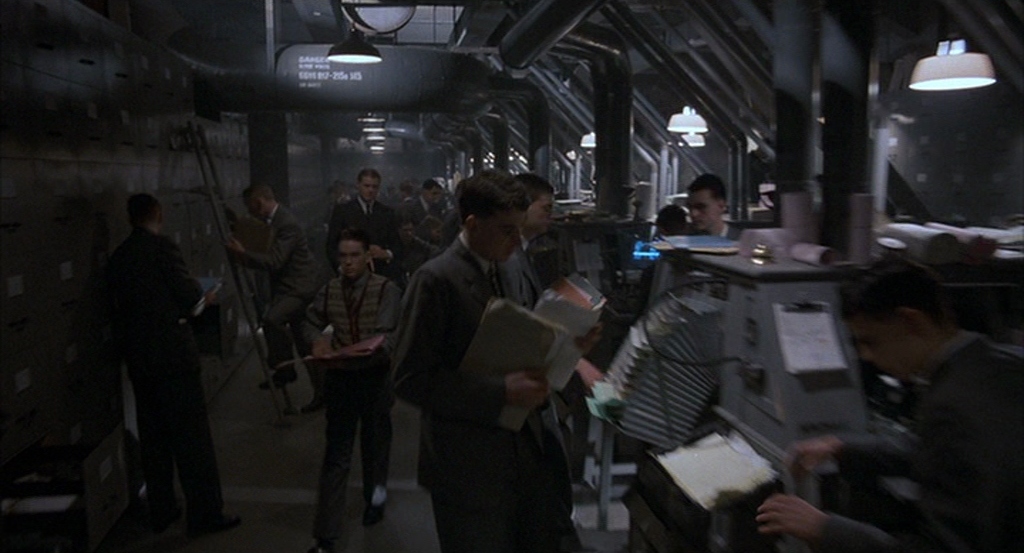

This is the world of Brazil. The lush, melodramatic, even self-obsessed fantasy of Sam Lowry contrasted with the grim world of bureaucracy he tries so hard to ignore. That world can be classified as dystopian—though, crucially, it is dystopian in a very specific way. Brazil is a dystopia of bureaucracy—a world in which persons of “interest” to the government are detained and then charged for any fees which ensue from their detainment. Yet almost everyone accepts this world for what it is. The horrors are not recognized as such; they’re everyday. The state’s violence is normalized by bureaucracy, and the bureaucracy is itself an aspect of that violence.

Lowry is part of this violence. He works in Central Services—a lowly department, “impossible to get noticed” as Lowry’s friend puts it, but that’s just how Lowry likes it. The film doesn’t really explore why Lowry is so set on staying under the radar working in a dead-end department, though it’s possible that one of the reasons might be a desire to avoid the horrors the government unleashes once you do actually get noticed. Film critic Keith Phipps shares this interpretation, theorizing that Lowry initially turns down a promotion to Information Retrieval “because he knows what goes on within its walls, and would prefer to remain within a less actively destructive wing of the bureaucracy.”1

Lowry certainly demonstrates a consistent desire to avoid his political reality throughout the film. When a radio broadcast is interrupted by the announcement of a terrorist bombing, Lowry immediately turns the dial to bring his music back. The diegetic music playing on the radio is the same track that scores Sam’s dreams of flying. The lush and stylized theme represents the world Sam wants to inhabit and cannot. Everything is breaking down around him in ways so obvious and dramatic that even Lowry, who has a talent for remaining lowkey, cannot ignore it. Although he tries to ignore it very much, Lowry’s apartment becomes so overheated one night that he sleeps leaning against the refrigerator. Later on, his apartment becomes a frozen landscape at the hands of disaffected and grudge-bearing heating technicians assigned to fix the initial problem (such “service” goes a long way to explain the alleged terrorist technician who drives the plot—Archibald Tuttle, played against type by Robert De Niro in a warm, fun cameo).

Bureaucracy is embodied most strongly in Brazil’s ever-present ventilation ducts. They appear in almost every interior in the film. They’re so present, in fact, that the film’s first scene features an infomercial about ducts which is interrupted by an alleged terrorist bombing: “Central Service’s new duct designs are now available in hundreds of different colors to suit your individual tastes,” a suave salesman says shortly before an explosion rocks the TV storefront on screen.

For being a society that’s defined itself in response to terrorist activities, we know next to nothing about the actual terrorists in Brazil. As Keith Phipps writes, “Viewers never learn what the terrorists want, or what their objections to the government are … The film shows only explosions, never the people instigating the explosions, who remain invisible and silent.”

I probably first saw Brazil when I was in high school, and I thought it was a delightful and lush fantasy about a strange, unassuming man living in a world of bureaucratic terror. Returning to it now after many intervening years and viewings, I find myself troubled by how complacent Sam is about the world he inhabits, and the part he plays in upholding a government that tortures its citizens for information and then charges them for the inconvenience. His only interest is the woman in his dreams, who turns out to be real, and once he’s seen her, he won’t stop until he finds her. That’s his motivator. Everything else is irrelevant.

The torture sessions in the film—which are not actually shown on screen until the very end—are staged like dentist appointments. A receptionist transcribes every scream and plea from the victim, and the torturer plays with his daughter in an adjacent office in between appointments. It’s maniacal and it’s normalized. When Sam talks to this torturer, who just so happens to be an old friend (portrayed by the always delightful Michael Palin), he shows mild alarm at the blood on his friend’s scrubs, but he doesn’t say anything.

This is the oppressive, scared world Lowry wants to avoid. But there’s no vision of reform in Brazil. The terrorist bombings are a background reality—unchanging, not worth commenting on. The only escape offered in Brazil is a mental one. Imagine that you’re in a better place. Dream of it. Keep it in mind. Or, as is the case with Lowry, become delusional as the result of prolonged torture (and perhaps a lobotomy), until your fantasy becomes your reality.

The ending images of Brazil: a mobile home couched in a sunken valley. Not a building or duct in sight. Brazil may be a comedy, but there’s nothing funny about the broken bureaucratic world at its center.

Bibliography

1 Keith Phipps, “Duct to the future: The nightmare of Brazil never arrived, but it’s still

resonant,” The Dissolve, August 7, 2013, https://thedissolve.com/features/movie-of-the-week/71-

duct-to-the-future-the-nightmare-of-brazil-never-a/.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon