| Finn Odum |

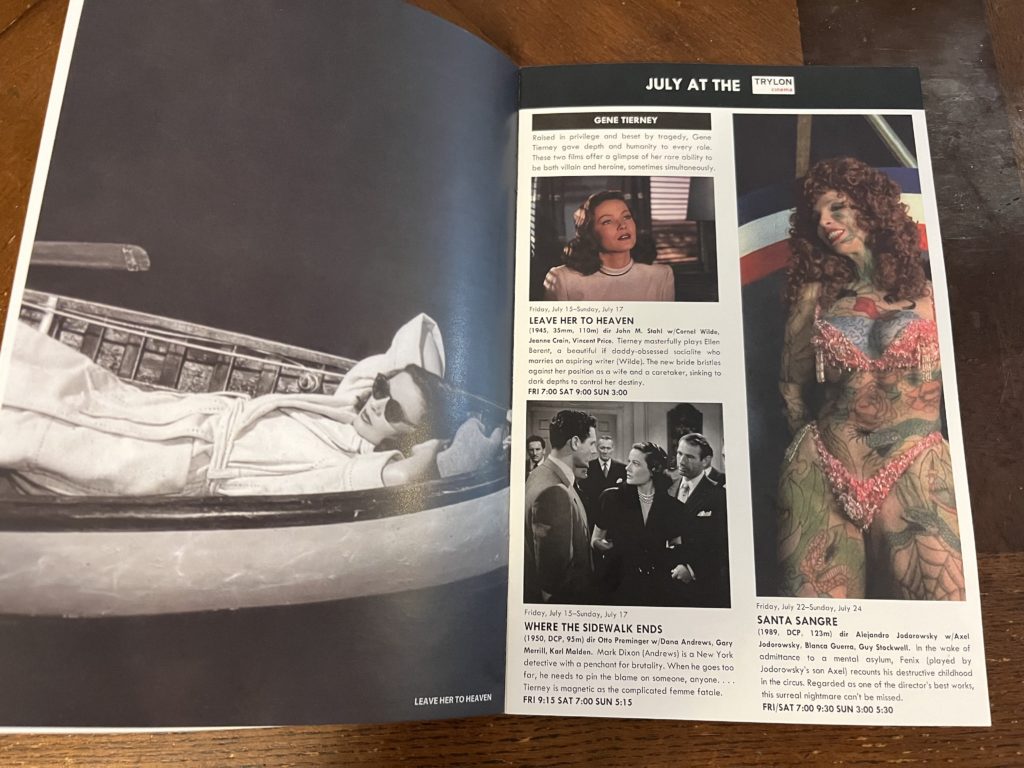

La casa lobo (The Wolf House) plays at the Tryon Cinema from Friday, May 31st, through Sunday, June 2nd. Visit trylon.org para boletos y más información.

I. Gringos en Arica

The first of my three weeks in Arica, a city on the Chilean-Peruvian border, was spent in a beachside hotel. We had free breakfast in the mornings, a pool overlooking the ocean, and most importantly, a bar just a five-minute walk away. Many of us were vibrating at the mere notion of buying alcohol. We were all 19 and 20 and otherwise not legal in the US; everyone bought the Modelo they saw on the counter or a poorly ordered mixed drink that made it clear we were Americans. Such is the experience of a 20-something student abroad. Find a new culture, barely speak the language, ask for their favorite form of alcohol. Wash, rinse, repeat.

I do mean “barely” speak the language; my Spanish is awful. In Chile, there was little I could do besides continuing my classes and attempting to break down with my host family the complex differences between “transgénero” and “transexual.” That and watching movies. But according to my program director, “No hay mucho cine en Chile.”

Pero, there was film in Chile: American films, mostly. I spent the first week in Arica searching for the local movie theaters and trying to sort through the subtitled Hollywood pictures, hoping I’d find something Chilean. During my first dinner abroad, our program director explained that the biggest film producers in Latin America were Mexico and Argentina. There weren’t a lot of Chilean movies in circulation, and even fewer Chilean horror films—the only one he remembered being a funny little thing named Santa Sangre, which was by a Chilean director but technically a Mexican production.

This was in March of 2020. Two years prior, the Chilean production La casa lobo premiered at the 68th annual Berlin International Film Festival. It was a fucking masterpiece that, for whatever reason, both my program director and I completely missed.

Trylon programmed Santa Sangre in the Summer of 2022, per Finn’s suggestion

II. Hay Cine en Chile

Contrary to my program advisor’s initial statements, Chilean cinema has always been on the map—just not on the US’s. Much of Chile’s rich film history is rooted in socialist theory. One of the most important movements was the experimental New Chilean Cinema, born out of film programs at the University of Chile and the Catholic University of Chile. Inspired by documentary films and the political uprising around them, directors from this movement focused on neo-realism, poverty, and politics.1 Films like Valparaíso mi amor and Three Sad Tigers depicted the lives of poor Chileans and the harsh reality of class inequality. New Chilean Cinema started to put the country on the map—until about 1973 when many of its filmmakers were forced out by the Pinochet regime.

Known terrible person Agosto Pinochet was a former military officer, a far-right figurehead, and a dictator who took power from the socialist Allende government with the help of the United States. With the country’s biggest artists—filmmakers—promoting leftist ideas, the industry crumbled under Pinochet’s rule. Cine Chileno became Cine Exiliado.

The exiled filmmakers documented their experiences away from the country, but the local film industry didn’t pick up until well after Pinochet was ousted in 1990. Their first major success, El Chacotero Sentimental, was released in 2000. It opened up the world to the potential of Chile’s film industry. Some of their biggest modern successes have revisited the “lost” years of Pinochet’s regime, showcasing what the New Chilean Cinema’s exiled directors couldn’t: a look at the country from the inside. The award-winning Machuca, for instance, tells the story of two boys from different backgrounds whose friendship is tested during Pinochet’s 1973 coup. Tony Manero is a drama set in Santiago during Pinochet’s regime, where the violence against citizens is a background piece. There’s also No, a 2012 film about the 1988 Chilean national plebiscite starring the ever-gorgeous Gael Garcia Bernal.2 And, on a smaller but still important scale, there’s La casa lobo.

III. La casa lobo

La casa lobo is about a girl named Maria who runs away from her commune and finds shelter in the woods. There, she befriends and mothers two pigs, whom she transforms into humans through strict rules and special honey. Outside of the house, a wolf haunts Maria until she begins to doubt herself. When the pigs, Pedro y Ana, suddenly turn on her, Maria calls upon the wolf for help. With his aid, she is welcomed back to the colony. She’s safe.

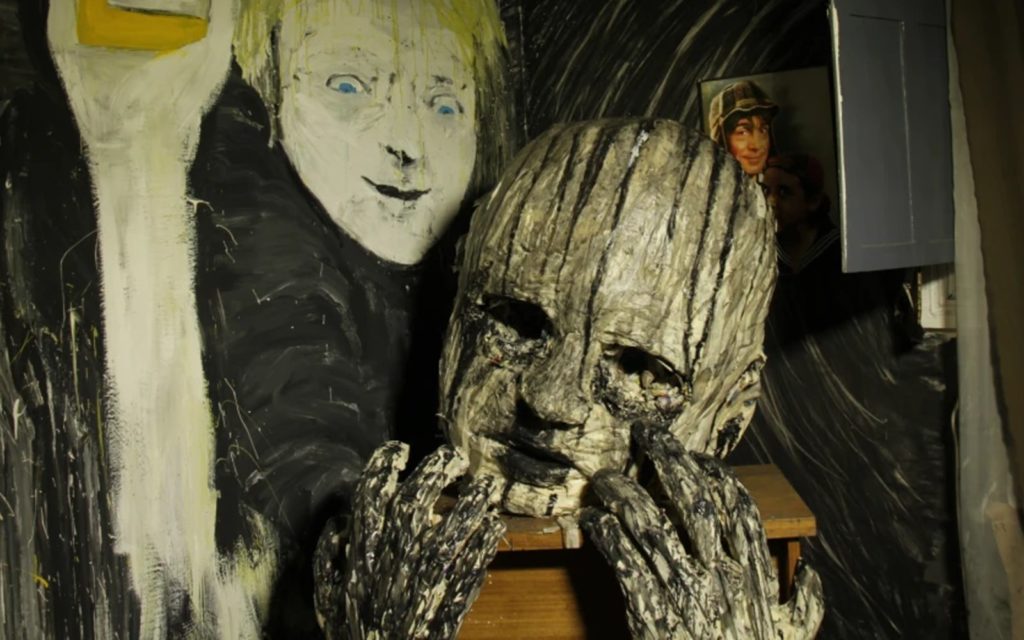

There’s also an absolutely haunting baby head.

It’s a simple story elevated by complex animation. Directors Cristobal León & Joaquín Cociña created their 2018 nightmare with a mix of clay, paper mache, paint, chalk, and puppets. The setting is in constant motion; characters are built and rebuilt as they move, the floors get painted to indicate motion. In one of my favorite effects, candles burn down over time and reappear, melting over and over and over. The characters are constantly changing mediums; Pedro y Ana go from being paper mache pigs to paper mache people to dolls and to chalk on the walls. The horror comes from the unsettling deconstruction, the bugs crawling out from painted shelves, and the black tape pouring from Pedro’s mouth. As excited as I am to see this in a theater, I will forever value being able to pause the screen on my laptop, freezing in time the frame-by-frame devolution of the children, to capture the blink-and-you’ll-miss-it moment where a swastika is hidden in a window as it’s painted onto a wall.

This is a movie about Chilean history. Set up by an opening live-action sequence depicting a sequestered German community, La casa lobo draws inspiration from the real-life Colonial Dignidad, a post-WWII colony established by Nazis. One of its longest-living leaders, Paul Schäfer, was a fascist pedophile and friend of, you guessed, garbage human Pinochet. You don’t need a critical eye to see this influence: throughout the film, Maria, who is a child from the fascist colony, turns two dark-haired children into blondes with blue eyes. The honey she gives Pedro and Ana doesn’t make them “better,” it transforms two otherwise indigenous Chileans into white Europeans. There’s also the scene where Maria admits that she got in trouble for giving her cult’s honey to non-white children. When Maria returns to the colony, she’s returning to the people who indoctrinated and controlled her—because she knows nothing else.

La Casa Lobo is a parable, a warning; in the opening framing narrative, an unseen narrator explains we’re about to watch a film made by the sequestered colony. The story that unfolds has a simple narrative and unsettling, child-like imagery because it is meant to indoctrinate. It is fiction—but based on a very true, very real occurrence in history. This imagery is indicative of the larger world of white supremacy. Nosotros Norteamericanos—we’d be wise to pay attention to the subtle ways that far-right ideology crops up in media.

The real-world Colonia Dignidad was loosely dissolved in 1991. In what I feel is a terrifying turn, the property is now operated as a tourist resort. Schäfer fled to Argentina after being charged as a child predator and was sentenced to 20 years in prison. The Chilean government began an official investigation into the cult’s activities in 2010. La casa lobo isn’t the first movie to tell the colony’s story—that’s the 2015 German Thriller Colonia, starring Emma Watson for some reason—but I think it’s the more successful.3 What better way to document a cult that turned into a resort than with an unsettling animated parable? It exposes a darker, underlying evil. We all can see violence. It’s the quiet indoctrination that gets under the surface.

IV. Arica, mi Amor

There’s no cool observation about why my program director didn’t think there was a big market for Chilean film. Maybe he just wasn’t that into movies. If he thought Santa Sangre was weird, there was no way he would have sought out something like La casa lobo.

The first and only movie I saw in Arica was the 2020 horror movie, The Invisible Man, completely in Spanish with no English subtitles. I loved it. I didn’t understand half of it and still haven’t rewatched it to this day. It’s a memory of the time just before the pandemic, before COVID split our world in two, before I graduated into adulthood, before all the befores that have shaped the person writing to you today.

It wasn’t La casa lobo—but perhaps that’s for the best. Living under the impression that there wasn’t a lot of Chilean film is what made me seek out Jodrowsky’s filmography, what drove me to explore what it was like to try and program international film. Valparaíso mi amor doesn’t have a US distribution, but what about its New Chilean Cinema peers? Missing La casa lobo in 2020 implanted a thirst in 2024 to learn. And to learn film is to learn history—to learn about exiled directors and artists is to learn how dangerous art was to the right—I’ve discovered more than I ever did in my three weeks in Arica, dove deeper into the texts of Chilean artists that I would’ve ignored had the pandemic not ended my program.

This one is for Arica, my love, and the artists that call you home. May you one day have your stories documented in a camera frame.

Footnotes

1 https://www.emol.com/especiales/festivaldivia_05/historiacinechileno2.htm

2 Noun: the direct vote of all the members of an electorate on an important public question such as a change in the constitution. Translation: We yeeted Pinochet from power.

3 Technically, La casa lobo’s production took five years, meaning production started around 2012/2013. Colonia began its principal photography in 2014. Also, why was Emma Watson in this? Is this what you do when you’re trying to distance yourself from your childhood stardom? Huh??

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon