| Dan McCabe |

The Earrings of Madame de… plays at the Trylon Cinema from Sunday, June 16 through Tuesday, June 18. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

The Earrings of Madame de…(1953) may be the last great work of the French “Poetic Realism” period. It certainly isn’t the only film that marks the end of a historical era in the development of motion pictures. What interests me about it is that usually movies evolve for commercial or technological reasons. The transition from Poetic Realism to the French New Wave is that rare time when artistic considerations moved the change in cinematic eras.

That said, when finances and technology move cinema to a new era, it’s no less interesting. Looking at how the artistic transition in French cinema compares to technologically and financially motivated transitions in American movies provides insight into where movies have been, and maybe a little direction on where they’re headed.

Louise dances with the Baron in The Earrings of Madame de…

Francois Truffaut dismissed much of French cinema of the 1950s as “cinema de papa,”1 which roughly translates to “dad movies” with the same sneer that music critics use the phrase “dad rock” to describe hair bands from the 1980s. However, France’s greatest filmmaker was not talking about The Earrings of Madame de…; indeed, he later separately praised the film.2 Instead, “cinema de papa” refers to the pale imitations of the French Poetic Realism that hit theaters during the early 1950s. The attitude that something needed to change in French cinema was a key idea of the French New Wave.

Earrings belongs squarely in the same camp as Poetic Realism masterpieces like Children of Paradise (1945), Beauty and the Beast (1946), and The Rules of the Game (1939). The plot, taken at face value, is quite absurd, but the intricate details of the set design create an intensely captivating picture. Like in Children of Paradise, the imagining of 19th-century France is so immersive that it almost doesn’t matter that the story in Earrings is little more than your standard love triangle centered on a MacGuffin.

It’s a beautiful film and a stunning example of setting shots used to create emotional effect, so the flaws in its plot don’t harm the experience. Take, for example, the scenes where Louise (Danielle Darrieux) dances with the Baron (Vittorio De Sica – yes, that Vittorio de Sica of Italian Neorealism). The room around them fades and we experience their infatuation with one another in focus, moving through a crowded room.

But when you have intricate beauty and provocative framing, who needs a plot anyway? That brings me to Alain Resnais’ Last Year at Marienbad (1961).

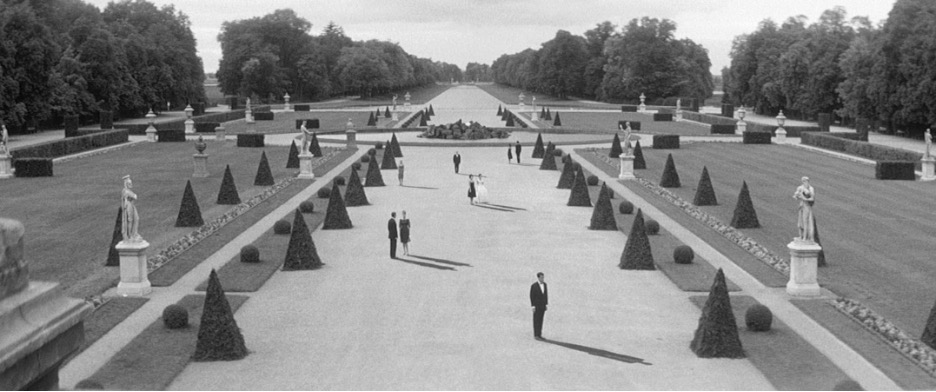

The pleasure garden from Last Year at Marienbad.

I’ve seen Marienbad three times, I’m just now starting to figure out what’s going on, and I’m certain that was Resnais’ point. French filmmakers could have kept pumping out beautiful, theatrically rich films like Earrings. Instead of building on that legacy, New Wave films like Marienbad tore it down, and rebuilt it as something different, something more creative.

Like Earrings, Marienbad features a woman (Delphine Seyrig) in love with a man (Giorgio Alberazzi) who isn’t her husband. Or is he? The film never really says. We know enough about films like Earrings to make assumptions based on behavior, but Marienbad leaves us hanging. It keeps the poetics, but drops the realism to send the audience into a dream state.

New Wave films challenged Poetic Realism and changed cinema forever, but not all changes in cinematic eras result from high artistic motives. In fact, I would venture to say that such artistic transformations are rare. I think it is more common that commercial or technological motivations change moved the development of the motion picture along its historical arc.

Say what you want about Heaven’s Gate taking down United Artists, it’s a pretty movie to look at.

Sometimes, cinematic eras end for purely commercial reasons. Plenty of failures have caused Hollywood studios to change course. The twin flops of Batman and Robin (1997) and Godzilla (1998) ended the era of the 1990s blockbuster. The disappointing box office returns Solo (2018) and The Rise of Skywalker (2019) caused Disney to abandon its plan to release a Star Wars film every year. However, as much as the aforementioned films failed to meet expectations, none took down an entire studio like Heaven’s Gate (1980).

Heaven’s Gate cost $44 million to make and only made $3.5 million at the Box Office. United Artists gave Michael Cimino, who had wowed the industry with The Deer Hunter (1978) a few years earlier, unlimited leeway to create his vision. The idea was that directors of the New Hollywood generation (including Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, and Martin Scorsese) should have any resources they need to create their masterpieces. After the failure of Heavens Gate caused United Artists to be swallowed up by MGM, studios took back controls from directors.

The commercial, however, is not altogether separate from the artistic. New Wave films weren’t only more artistically interesting than the French films that came out after Earrings; they made significant money, and made international stars of their cast and directors. Heaven’s Gate demonstrated the limits of giving a director total control. While Heaven’s Gate’s reputation has increased over the years, it was not well regarded when it came out. In fact, in my opinion it belongs in the same bucket as Waterworld (1995) and Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace (1999): films that gave one person unquestioned authority with poor results. Although all three of those films have their defenders, the lesson of their consensus assessment remains that, even if you apply the auteur theory of cinema, directors can sometimes benefit from somebody telling them about their bad ideas.

Toy Story (1995) was the first feature-length, computer animated film. It is regarded as a masterpiece.

As film technology changes, eras defined by that technology also end eventually. The Poetic Realism-New Wave transition isn’t the best analogue for this, of course. Moviemaking technology improved between the 1950s and 1960s, but not that much. There was no sea-change like the transition to sound in the 1920s. In fact, there is only one comparable technological change in the medium since the age of the silents ended: the advent of computer effects.

Computer effects have not entirely replaced conventional effects in live-action films, but American studios have largely abandoned hand-drawn animation. The last Disney hand-drawn features were The Princess and the Frog (2009) and Winnie the Pooh (2011). However, the studio had struggled in the animated feature area since the late 1990s, relying heavily on Pixar films to bring in the bacon (no offense to Hamm from Toy Story (1995)). Computer technology not only made animated films easier to make, but it also proved more popular.

But that’s the thing, isn’t it? Audiences loved sound films, widescreen format, computer effects, and computer animation. They even enjoyed 3D movies for a minute or two (in the 1950s, and again for a brief period in this century). The technology is tied to the commercial is tied to the art.

Louise admires the titular Earrings of Madame de…

That brings me back to Earrings. Why does matter that it’s the last great masterpiece of French Poetic Realism? Because it’s useful to categorize any artform into different movements. The same is true for music and the visual arts. Bookending an era gives the film a special place in history and helps us understand the progression of movies as an art form.

One can see little pieces of Earrings’ beauty and absurdity in the films that came after. If you follow those threads long enough, they go all the way to the present day. Perhaps, like a certain jewelry shop, we buy and sell the same magnificent earrings as film viewers, again and again, each time for a different purpose.

Footnotes

1 François Truffaut, “A Certain Tendency in French Cinema,” Cahiers du Cinéma 31 (January 1954). 15-24.

2 François Truffaut, The Films in My Life, New York: Da Capo Press, 1994, 32.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon