| Ben Tuthill |

Casino plays in 35mm at the Trylon Cinema from Sunday, December 21st, through Tuesday, December 23rd. For tickets, showtimes, and other series information, visit trylon.org.

Casino is the only entry in Martin Scorsese’s catalog you might confuse for self-parody. Three different voice-overs, a United Nations of ethnic slurs, so many Rolling Stones needle drops that at one point there’s a Rolling Stones song playing over another Rolling Stones song—it’s reasonable to wonder if, by film number fifteen, Scorsese was fresh out of ideas. Casino drives pedal-to-the-floor for three hours straight but somehow goes nowhere, everyone inside either oblivious to the stationary scenery or dead on fumes.

At the risk of giving Scorsese a free pass, I think this wheel-spinning is the point. Casino is a film of exhaustion, the culmination of a career phase that explores a certain form of masculinity through a certain collection of cinematic tropes. The result is a period (or maybe three of them) and a good riddance, Scorsese’s statement that he’s finally ready to move on to bigger and better things. It’s not quite a turning point in his career, but it’s the last step before a wilderness from which will emerge a radically different filmmaker with a radically different interpretation of American masculinity. In other words: Casino, with a very large asterisk, is Scorsese’s last Robert De Niro movie, and that Means Something.

The key to understanding Martin Scorsese is that he’s a director of avatars. He’s essentially processing one question—what does it mean to be a man in this world where only one of us is Jesus Christ?—and he’s doing it through male protagonists who stand in as the questioner. For the first half of his career, he interrogates a masculinity specific to his Elizabeth Street upbringing: gangsters, tough guys, men who make big gestures with their hands and get emotional about pasta sauce. If anything comes across in Rebecca Miller’s five-part documentary, Mr. Scorsese, it’s Scorsese’s agony that he—a short, asthmatic kid who literally had to spend his summers in refrigerated movie theaters to stay alive—could never be that kind of man. And furthermore, he knows his desire to be that man is wrong, because, as a good Catholic, the only man he should be emulating is Jesus. Being inherently fallen and bad at sports is a cocktail for self-alienation, and what better way to process it than to create movies where someone totally unlike you plays yourself?

Scorsese’s first avatar is Harvey Keitel (tough, Brooklyn, Jewish), but in Mean Streets he meets the actor who will define the first half of his career, the real-deal Little Italy street kid from one block over, Robert De Niro. Except, of course, it’s a lie: Robert De Niro is the embodiment of phony Italian masculinity. Robert, Sr. was a half-Irish painter from Syracuse who studied at the Black Mountain institute, married a Dutch-German Presbyterian named Virginia Admiral, came out two years later, and insulated his son from Lower Manhattan street culture by enrolling him in the New School youth theater program. An imposter with an Italian last name enacts the exact falsity Scorsese is looking for, and De Niro takes center stage for the next decade. They travel together into the depths of toxic masculinity long before it had a name, from proto-blackpilled psychosis in Taxi Driver (1976), to deadbeat abandonment in New York, New York (1977), to explosive sadomasochism in Raging Bull (1980), and finally to full basement-dweller derangement in The King of Comedy (1982).

These four films are some of our greatest depictions of the way men abuse their bodies and their souls to prove themselves as men. What’s easy to miss is that, with the arguable exception of New York, New York, all of these protagonists are losers. In a post-Heat world, we think of De Niro as the embodiment of gravitas, but his initial run with Scorsese is a gallery of failures. If there are victories in these films, they’re materially and spiritually empty. Travis Bickle’s news clipping, Jake La Motta’s Brando impression, Rupert Pupkin’s fantasy comedy set: these are the participation trophies of life, empty reminders of a failed grasp at Great Man status—and the audience knows it.

Scorsese spends most of the 1980s doing what he needs to do to make The Last Temptation of Christ, so it isn’t until the 1990s that he gets back to working with De Niro. Instead of continuing the loser cycle, Scorsese starts to push away, shifting De Niro from protagonist to villain in Goodfellas and Cape Fear. There are new ideas percolating about deceit and faith and capitalism, and Scorsese seems ready to leave Elizabeth Street behind. But there’s one last step before he can excise his demons: he needs to see what happens when his avatar becomes a winner. The obvious choice would be to make another Little Italy gangster movie with De Niro in the Brando/Pacino role. Instead, he crafts him from the most alienating material he can find: he makes him Jewish, he puts him in Las Vegas, and he lets him get torn to shreds by Sharon Stone.

Sharon Stone is the moral center of Casino, the element that prevents it from becoming Scorsese’s most generic film. Stone plays Ginger McKenna, an unspecified “hustler,” against De Niro’s Ace Rothstein, a sports handicapper sent by the Midwest mob to run the Tangiers Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas. The dangerous blonde isn’t an especially groundbreaking role in a gangster movie, but Scorsese takes the novel approach of promoting her from accessory to full-on foil, creating a real role for Stone to embody without the up-down camerawork that typically limits women in gangster films to their sexuality. We’re told by the script (and by the fact that she’s Sharon Stone) that Ginger is beautiful, but we get none of Verhoeven’s abusive leering or the aooga treatment Scorsese would later apply to Margot Robbie in The Wolf of Wall Street.

Instead we get a masterfully unhinged performance as Ginger tears apart the gilded world of masculinity that surrounds her. Sharon Stone screams, kicks, smashes cars, curls into balls, and so far exceeds every harpy-moll trope that any illusions of stability in the gangster/wife/goomah relationship are shattered before they can stick. Casino is packed to the gills with domestic disputes, but the scene that sticks in my head is a small one where Ace, dressed in a pastel bathrobe, guides an intoxicated Ginger, dressed to play tennis, down a spiral staircase. Ginger doesn’t say a word, but the lipstick-framed sneer she throws over her shoulder says more than 180 pages of screenplay. This man, an absolute winner at the peak of his powers, is a disgrace. This woman, blasted out of her mind and nowhere near the vicinity of making it to her morning tennis match, knows it. She’s the only one who knows it, and she’s willing to ruin her life to prove it.

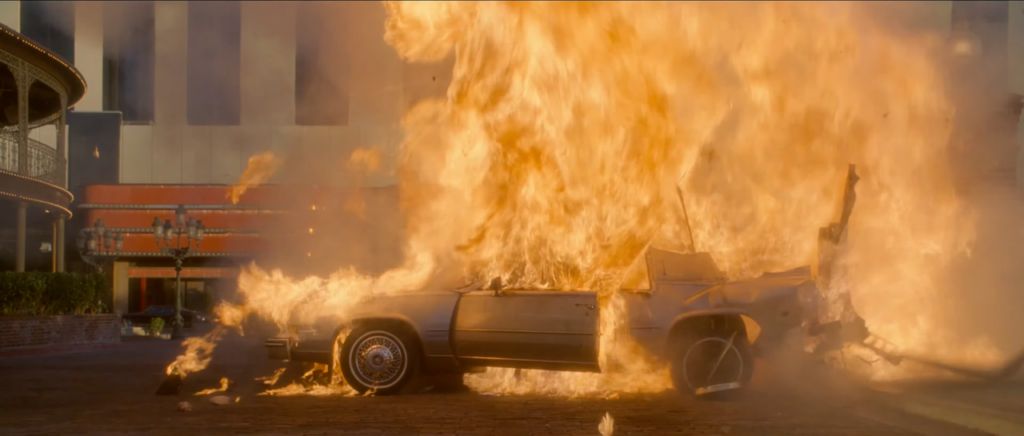

Stone screams in Casino what Scorsese has been muttering for years: this mode of masculinity, for all its material success and cultural adoration, doesn’t work. It’s easy to equate Scorsese’s perspective with Ace’s, but, despite the deifying sheen his camera casts over De Niro, our sympathies land with Ginger. It’s never exactly clear why she hates Ace so much—there’s no explicit infidelity, no drugs, no abusive control, no domestic violence. She just hates him enough to steal his money, tie his child to the bed, smash up his car, and—the gravest sin in this kind of movie—rat him out to the feds. From start to finish, Ace has no conception of what he could possibly have done wrong, and neither does the screenplay. Alienated from all sense of decency, both camera and character are oblivious to anything beyond Ace’s drive to win.

There’s a meanness to Casino that isn’t present in Scorsese’s other films. The brutal conclusion of Joe Pesce’s character is one of the hardest-to-watch moments in Scorsese’s filmography, but it’s Ginger’s anonymous overdose in a hotel hallway that feels the most abusive. The amoral callousness proves the moral alienation. Ace steps out victorious while his wife is buried in the equivalent of the unmarked holes that dot the Nevada desert. The only death he mourns is the razing of the Tangiers and its replacement by the cartoon lion’s head of the MGM Grand. His concluding voiceover bemoans the change like it’s the loss of a golden era, as if the corrupt Las Vegas of the 70s and 80s was any less depraved than the junk-bond Las Vegas of the 90s.

But Ace still comes out on top. He ends the film alive and well, back to sports handicapping. “I could still pick winners, and I could still make money for all kinds of people back home. And why mess up a good thing? And that’s that.” In the end, as in the beginning, it’s all about winners, and Ace is convinced he’s one of them. Scorsese won’t give us any cinematic indicators to tell us otherwise. Like Bickle’s news clipping and Pupkin’s Late Night routine, it’s up to the audience to assess the truth.

Casino is the end of Scorsese’s De Niro era, the last time they’ll work together until the coda of The Irishman. And it’s very much the end of a certain phase in Scorsese’s career, the last time (again, until The Irishman) he’ll work with this particular kind of gangster. He goes to Tibet for his next film (Kundun), then back to New York but through the eyes of an EMT (Bringing Out the Dead), and then it’s on to the next long phase of his career, the ongoing collaboration with Leonardo DiCaprio that explores a very different sort of masculinity. Ace is his last Little Italy man. He’s not even Italian and he’s not from New York, but, in the economy of Christ, he’s still a loser. Far from home, comically oblivious, and outdone by a woman—it’s the only place where Scorsese’s exploration of Elizabeth Street masculinity could end.

Edited by Olga Tchepikova-Treon