|Finn Odum|

Miss Congeniality plays at the Trylon Cinema from Friday, February 23rd, through Sunday, February 25th. Visit trylon.org for tickets and more information.

Several weeks ago, in the monotonous gray cubes of the Mall of America® office tower, I dared to make a joke about my gender identity. This is how it went:

Finn, 24, strikingly gorgeous and wickedly funny email specialist: Now, I’m not like most women—in that I’m not one.

[Finn pauses to laugh]

[Male coworkers, aged generously between 30 and 50, remain dead silent].

Finn: That’s a gender joke. You can laugh because I made it.

In the defense of my cohort, only one of them is queer, and the rest seemed to be accepting but otherwise uninformed on the issues of gender and sexuality. Early on in my tenure at the mall, I explained to my boss the nuances between “Non-binary” and “Gender neutral,” and why you’d assign one to a gender identity but not the other.1 They’re starting to get the hang of things, I think; just last week, when a Black colleague and I were politely mocking my white male supervisor for his privileged identity, our dear loyalty manager joined in to point out that the man in question was also cis-gendered.

Because I am a.) obnoxious and b.) a one-time stand-up comedian, I informed him he wasn’t allowed to make that joke. After all, I’m the closest thing to a trans person in the office, not him. He played along, questioning if it was fair for me, a younger person, to come at him, a man who is (once again) generously in his 40s. It was a joke, and also a very, very pertinent question. Who has the right to make a joke about marginalized identities? The obvious answer should be that only someone from that identity group can make those jokes—but given the larger history of poor-taste jokes, punching up, and so-called dark humor, it’s not as clear as it should be.

I’ve been thinking about this a lot lately, in both my personal life and the media I consume.

Months ago, well before we announced we’d be screening Miss Congeniality, I ran across a joke from the film’s third act. It caught me one night after a glass of Yellowtail sangria and a good time, floating across my Deceased Bird App dashboard.2

I want all the lesbians to know: if I can make it to the top ten, so can you.

I was shocked. Awed. Amazed, even. What 2000s era movie could this have been? Then comes the quick pan to Sandy Bullock. The beauty queen’s girlfriend in the audience screams, “I love you, Karen!” William Shatner’s here? And before I can process any of that, someone asks, “Can we say lesbians?”

The clip ended. I watched it again. Clip ended. I watched it again.

The one time I’d watched Miss Congeniality I was but a babe, a child, baffled by the strange comedy my conservative grandmother had thrown on TV. I remembered the S.I.N.G. sequence and nothing more. But this joke—this tiny, one-off bit—it read to me like something that I, a 2024 bisexual, might write for myself; not a line wedged into 2000s Sandra Bullock comedy, written and pushed primarily by straight people.

Director Donald Petrie was proud of that line, claiming it would help elevate his film to a higher purpose. But it was a joke, not just a piece of dialogue, with the intention of making the audience laugh. Did the writing team have the right to make their one “out” queer character a comedic beat? Was Miss Congeniality a subversive sleeper hit?

I mean, no, obviously it isn’t. It’s hard to even consider its takes on gender subversive, as Petrie didn’t consider pageantry a serious matter.3 On paper, it is indeed a comedy about a woman unlearning her biases about femininity and female friendship. In action, it maintained harmful ideas about body image and beauty standards. There’s also the only in-performance and never-explicitly gay Michael Caine character, who gets a single joke in the third act to gesture at naming his sexuality. And Karen? Poor, iconic Karen? There’s not a beat that suggests she’s queer until they need to make it into a joke.

When I set out to write this essay, I thought it would be about the nuance of queer comedy and representation in the early 2000s. Maybe I’d sneak in some takes about gender performance, what the film got right, and where it could’ve improved. And while I’d like to affirm that Miss Congeniality isn’t all that and a banned-from-craft-services bag of chips,4 that’s not what I got out of the movie. I enjoyed watching it. I’m glad I watched it. I wish I remembered watching it all those years ago. Because there’s a chance that maybe, maybe, a younger version of me who recalled the characters in this film would’ve realized that I was going to be okay.

To write that into being is almost silly. Coming out wasn’t as hard for me as it was for some of my friends and peers. The Methodists were pretty accepting—those who stayed with the church post the 2020 split over gay rights, that is—and both my public Milwaukee high school and my cushy liberal arts college were (usually) welcoming places for queer folks.

And yet, it was so easy to slip myself into Miss New York’s blistering high heels and think about what it’s like to have that weight of gendered expectations on your shoulders. I imagined, for a moment, that I was competing in a space where the idea of a woman was so strict, so thin in personality and body expectations, that the very thing that set me apart was buried in the ground. Suddenly, I wasn’t imagining it anymore; I thought of the years in my childhood when I was too embarrassed to tell my friends that I was remotely interested in girls at the risk of social exclusion. Those fleeting weeks at a weird church camp where we, the thirteen-year-olds of Wisconsin, were asked to give our “immoral thoughts” over to God. I thought of the years I spent in college fighting for our Christian student group to say something—anything—that condemned homophobia. To my relatives, the very few who may not know, and may never know, because they don’t have it within themselves to reckon with a loved one being queer.

I thought of everything that this poor side character must’ve gone through, down to being carted off the stage as she shouted her truth to the world. At the same moment that I’m annoyed, ready to rail on the rhetoric of 00s era comedy—Karen, Miss New York, is declaring her love for her girlfriend in front of millions. It’s a joke, it’s not a joke, it’s barely representation, it’s representation.

And then it’s over. We’ve swung back to Sandra Bullock’s Grace Hart, the masculine protagonist forced to compete in a beauty pageant. At the end of the film, she’s gained friends and a new appreciation of heels, but returns to her typical suit and tie wardrobe. I wasn’t dazzled by her character development—more irritated by her demeanor than anything else—and ended up almost disappointed that she got together with her male coworker.

And yet, as I downed my second glass of Sauv Blanc while preparing for this essay, I realized I empathize with Grace. For many many years of my youth, I thought femininity wasn’t attainable. I didn’t deserve it. It didn’t make sense for the kid who’d play Prince Eric with her friends to be “girly.” Illogical, one might say, when my sister was already the one who liked pink. I bemoaned my more femme friends demanding we have a dress day in high school and lamented when my one-time boyfriend bought me (gasp!) a rose for homecoming. There was no name for this discomfort—because I wasn’t a transman, nor was I a butch lesbian; I hated the notion of feminine behavior because that wasn’t the “type of woman” I was.

It’s not the type of woman Grace Hart was either, but she still learned something at the end of the film. She unlearned, actually; unlearned her biases, the preconceived ideas of airheaded pageantry she’d bought into after years of working with 2000s-era men. Not only does she learn, she teaches others to embrace all of themselves. She accepts the love and support of those who represent everything she once despised—and those who forgave her for any misconceptions because they saw who she was on the inside. At age 28, she learned things that would take me several years to unpack in a matter of a week.

As you might’ve ascertained, I’m coming to you live in 2024 as not a woman and not non-binary, but some secret third thing. I’m less of a man than anything else, potentially androgynous if you squint, and Lovecraftian if you read my texts to my mother. That discomfort with femininity I felt for almost two decades—it wasn’t because I was undeserving. I was never undeserving. Like Grace, I had convinced myself it was never attainable.

I wonder if finishing Miss Congeniality at a younger age would’ve assured me it was okay to be both masculine and feminine, that I didn’t have to choose one and demean the other. While it would’ve had no bearing on my gender identity, it could have reminded me that I too can walk the line of throwing people around in evening gowns.5 That there’s room for queer people on stage alongside the Sandra Bullock’s and William Shatner’s of the world. That I am who I am, and that’s perfectly okay.

If you’re new around here, I’m Perisphere editor Finn. I’m still figuring it out.

And yet,

If I can make it far enough to become the co-editor of a local film blog, to learn how to be happy with myself, to be able to share this with an audience over a silly Y2K pageant,

Then all you bisexuals out there can do it too.

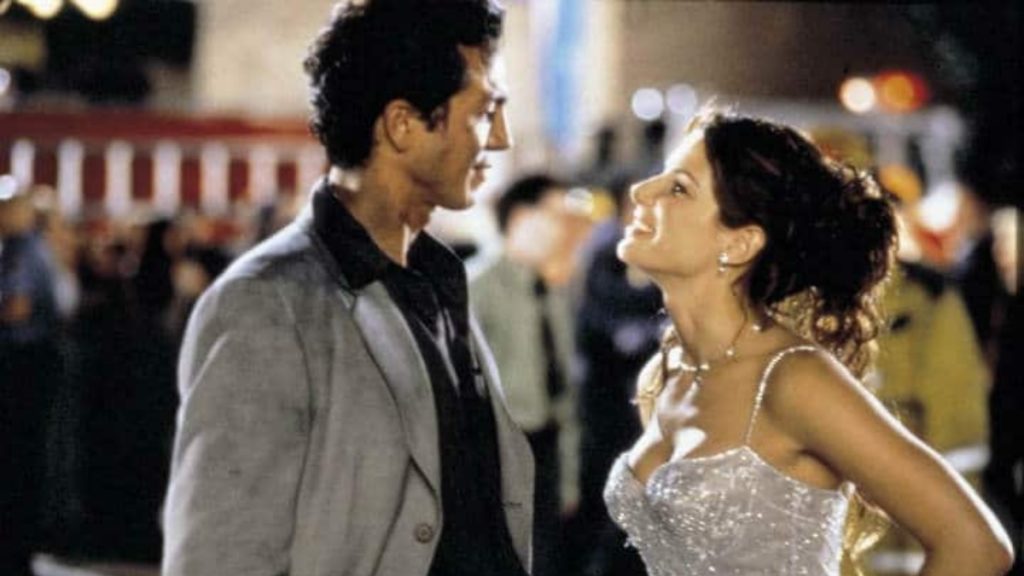

Perisphere editor Finn (pictured right) with their mother (pictured left). Finn thanks both of her parents for their support over the years and offers them one free therapy session every time they read one of Finn’s essays mentioning hot men. Thankfully, this was not one of them.

- In this example, “Gender Neutral” was being used to describe a gender identity, and while I recognize there are definitely some gender nonconforming people who would use it as a label, the more fitting descriptor was non-binary. I went on to comment that you wouldn’t say non-binary clothing, then walked that back and clarified that I could actually say something was “non-binary clothing”, because I wasn’t cis, and thenproceeded to explain that joke and why I was allowed to gently make fun of other gay people. You can see how comedy is complex over at the Mall of America. ↩︎

- If my job isn’t calling it X, I’m not calling it X. ↩︎

- “In my opinion, if you take a pageant absolutely seriously, that’s funny,” Donald said. “If you try to make a joke of a joke, that’s not funny.” Donald Petrie, in a 2021 interview with renowned intellectual journal E! News. ↩︎

- In the same E! News…article…Petrie explains that he also had to ban junk food from the craft services tables because the actors would be “wearing swimsuits on screen.” Oh, what, they can’t gain weight? That’s BAD? RIVETING TAKE, DONNIE. ↩︎

- There’s a rugby tradition we call “Prom Dress Rugby.” It’s exactly what it sounds like. ↩︎

Edited by Matthew Tchepikova-Treon